East Flatbush, Brooklyn, is where the city named a street after Bob Marley; where the rappers Busta Rhymes and Shyne and Joey Bada$$ came from; where one intersection is called the Front Page for its high-profile murders and another the Back Page because its murders get less press. It’s also where a young rapper named Ackquille Pollard grew up, in the shabby prewar apartment complex at 139 East 53rd Street, on the outer reaches of Clarkson Avenue.

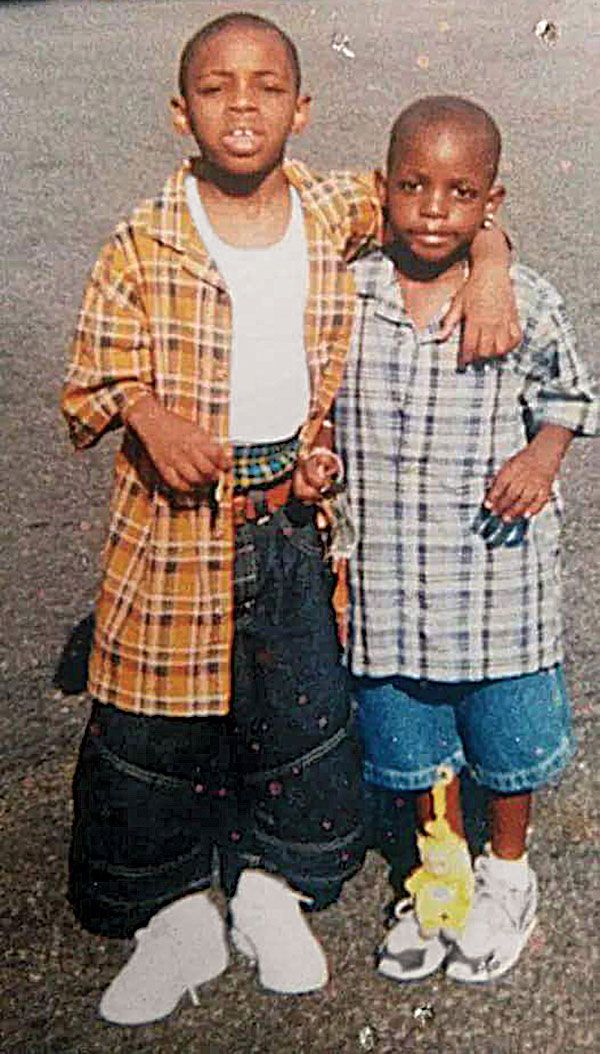

When Pollard was a kid, the courtyard soundtrack, furnished by a boom box, mixed 50 Cent and Lil Wayne and Trick Daddy with West Indian dancehall and R&B. Ackquille and his friends would hang out there and practice rhymes. Everyone had a nickname. Javase, his older brother, was Jaja. Another pair of brothers in the building, the local basketball stars Chad and Remy Marshall, were Rowdy and Fetti. From down the block came Rashid Derissant, or Rasha, the crew’s jokester; Alex Crandon, known as A-Rod, soft-spoken and laid-back; and Brian “Meeshie” Harvey, loud and brash, with a deep scar on his right cheek. Pollard was younger than most of the others, something of a mascot until he wormed his way into the action. His large, blindingly white upper deck of teeth sold his smile from blocks away; the others called him Chewy. “I got one brother, but it’s like I got a group of brothers,” Pollard later said, “in the building I grew up in.”

His mother, Leslie Pollard, had worked in customer service at Verizon in the city, raising Ackquille and Javase with help from their grandmother. The boys’ father, Gervase Johnson, was charged with attempted first-degree murder when Ackquille was 2 months old and is serving a life sentence in Florida. When the boys would visit him in prison, he would walk the grounds with his sons, reminding them of two somewhat contradictory lessons: Stay off the streets, and keep your circle of friends close.

Ackquille loved reggae, the music of his West Indian father, and rap, which his brother turned him on to, and Michael Jackson, which he danced to everywhere his mother took him, disrupting even a simple trip to the barbershop. “Everything would shut down,” Leslie says, “and all the attention would be on him.” He sometimes worked on his own songs. With a laptop and headphones, he made his first remix when he was about 10, a take on Crime Mob’s “Knuck If You Buck.” “I was mad young,” he later boasted. “We did that and had the hood going crazy.”

When Pollard was 14, one of his friends, Dondi Williams, was shot at a graduation party in Brownsville. Two strangers had showed up and shot into the crowd. The murder was never solved. Pollard remembers waking up in the middle of the night to what sounded like gunfire off in the distance. The next morning, “I see his whole family crying and stuff. I just started crying. It was crazy.” The local councilman led a march to protest the violence.

Pollard’s first arrest came a year later, an assault charge during a street fight. He got probation and then violated it by smoking pot. He was sent to Graham Windham, a residential alternative-to-incarceration program in Hastings-on-Hudson. He hated being away from home, often demanding his mother drive up midweek to drop something off as an excuse to see her. “My child is extra-needy,” Leslie says. He came home to the courtyard on the weekends, playing basketball and the sidewalk game skelly, dancing, writing raps, and, he says, accompanying his older brother and his friends when they went to sell crack.

He was 16 and almost through his time at Graham Windham when his friend Tyrief Gary was gunned down at a block party. They’d spoken just a half-hour or so before the shooting; Pollard had been home for Brooklyn’s West Indian Day Carnival, the three-day string of parties and dances that clog the streets over Labor Day weekend. They were supposed to meet up, but Pollard never made it. Tyrief had been long on charisma and extroversion, just like Pollard. “He had all the girls around him,” Pollard says. “He was brave. He was a little crazy, too.”

To the police, at least, Tyrief — or Shyste, as he was known in East Flatbush — was also the leader of the G Stone Crips. The shooter was believed to have been a member of a gang called Brooklyn’s Most Wanted, or BMW, who had been barred from the party and decided to retaliate. According to the police, those gangs, along with a third crew called Folk Nation, have been fighting ever since.

But the concept of a crew can be nebulous — not a gang, exactly, but not not a gang, either. Unlike the highly organized gangs prominent in the 1990s, like the Crips and Bloods, criminologists believe today’s crews are less centralized, often more interested in controlling one block than one borough or one city. (The police have identified more than 300 such crews across the five boroughs.) But not all crews are even that organized. Sometimes a crew is kids on a corner selling crack. Sometimes it’s a bunch of kids sitting around and making up their own raps. But part of the appeal of a crew is that only the people in the crew know the real deal.

Pollard never publicly called his crew the G Stone Crips. He preferred GS9, an abbreviation that carried any number of meanings and references: Gun Squad, the G-Star clothing line, God’s Soldiers, God’s Sons. “GS9 is the squad,” he told Complex last year, as he was becoming famous. “That’s the family.”

He used another name too. “The Shmurdas is my brothers,” he said. “We was Shmurdas before GS9.” So where did “Shmurda” come from? He placed an index finger on his lips. “Shh! Shmurda.”

The day of Tyrief’s murder, in 2011, Pollard was arrested in a neighborhood sweep and charged with gun possession. When the gun was shown to be inoperable, the case was dropped, but that didn’t matter: He’d had “police contact,” which meant he could not return to Graham Windham. Instead, he was sent to a medium-security juvenile-detention center upstate, where he stayed until the spring of 2012.

“I’m never going back,” he told his mother when he came home. He’d taken a lesson from his friend’s death. “You got to control your temper and be smarter. You got to think about the future. You can’t just live for today.” He started taking music more seriously. “I’m gonna be rich,” he said.

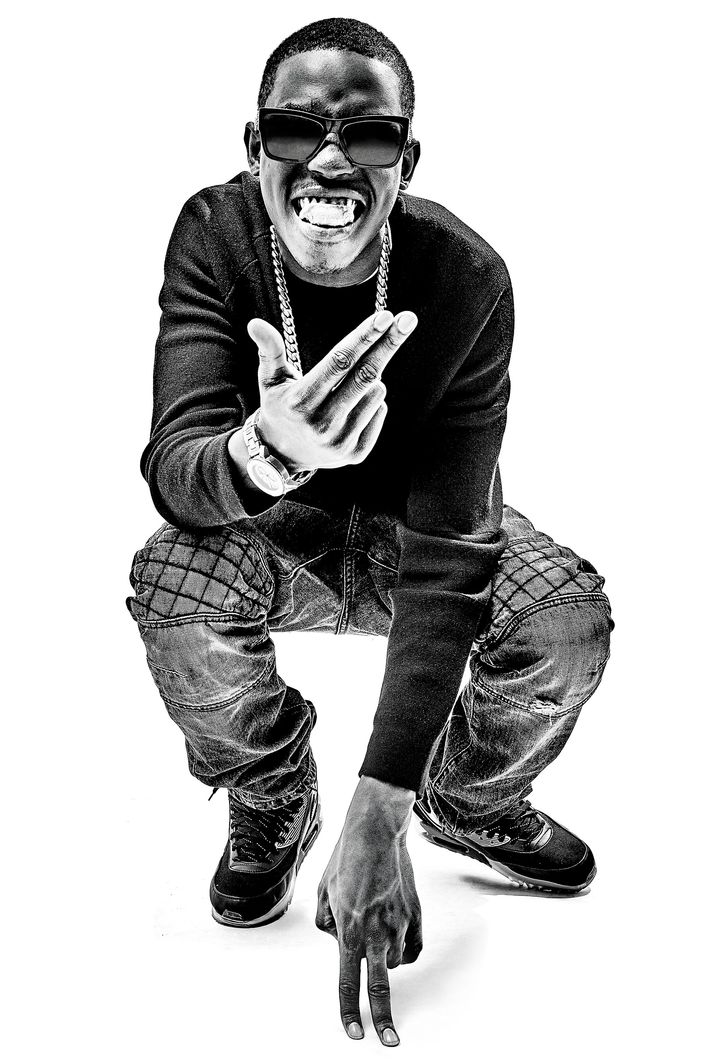

His crew, GS9, was a rap group now; on one level, they’d always been, freestyling in the courtyard. Chad Marshall was Rowdy Rebel now; Rowdy wrote raps, no doubt influenced by his father, one of the few dads present on the block, who had been part of an earlier rap scene in the ’80s. Pollard experimented with stage names — Bobby Savage first, then Bobby Shmurda.

But GS9 wasn’t just a rap group, at least not in the eyes of the police. The January after Pollard’s release, shots were fired outside Kings County Supreme Court in Downtown Brooklyn. Members of both GS9 and BMW were supposedly there, including Pollard. Police never figured out who fired a weapon, and no one was charged. That might have been the end of it, if Rasha and A-Rod hadn’t been caught on video at the site of a murder a few weeks later. The victim was a 19-year-old member of BMW who had been followed to a bodega on Clarkson Avenue in the middle of a snowstorm. Three other BMW members survived, only to become targets in future shootings. The attacks seemed to be less a coordinated assault than a series of reckless, opportunistic potshots, the two crews going at each other whenever and wherever they could. They missed their targets constantly and sometimes had trouble finding working guns in time to use them.

After the bodega murder, the police set up wiretaps on members of GS9. Pollard popped up on a few phone calls. In one early call, Ackquille tells his brother Javase, “You know I suntan him and shot, do issues, you know what’s going on.” One prosecutor believes this was Pollard expressing his “concern about retaliation” — “suntan” meaning “to shoot” — though police never connected the statement to any particular incident. In another call, Pollard is recorded telling his friend Slice to cool it after Slice got caught selling crack to an undercover cop: “You don’t know when the streets is hot. You going to learn, son, you going to learn the hard way.”

On the calls, Pollard sounds less like a criminal mastermind than a kid who grew up in a tough part of Brooklyn, where guns and drugs and violence were part of the landscape — as was music. An older guy in the neighborhood had turned his basement on 51st and Clarkson into a home studio. Ackquille and his friends would pull all-nighters there. The fees were low, paid for by Leslie. He and Rowdy collaborated on raps they released that winter as GS9. Soon after he got out of detention, Pollard found a beat he liked on YouTube from the producer Jahlil Beats. “I was so happy,” he said later. “It fit perfect.” That beat formed the foundation of the song that changed his life.

“Hot Nigga” is a chantlike rap earworm, a little like Chicago drill, a little like southern trap, each line landing defiantly hard on the N-word. The first lines are all bravado, starting with a salute to his old friend Tyrief — “I’m Chewy, I’m some hot nigga / Like I talk to Shyste when I shot niggas.” There’s guns (“Try to run down and you can catch a shot, nigga”) and money (“Running through these checks ’til I pass out”) and sex (“And shorty give me neck ’til I pass out”) and many shout-outs to his crew, including Meeshie and Breezy, who were behind bars:

I’m with Trigger, I’m with Rasha, I’m with A-Rod / Broad daylight and we gon’ let ’em things bark / Tell ’em niggas free Meeshie, ho / Some way, free Breezy, ho / And tell my niggas, Shmurda teamin’, ho / Mitch caught a body about a week ago.

He’d later claim the body Mitch “caught,” a murder reference, is fictional, though Mitch himself is real — the nickname of Dashain Cockett, a friend of Pollard’s who had joined GS9. “It’s all about me,” Pollard said last year. “I’m telling you about my past, my life. Everything’s real. Stuff I’ve been through, stuff I’m dealing with now, stuff my friends and family been through. To express my feelings. Like a journal, really.”

The “Hot Nigga” video, released on YouTube in March 2014, seemed every bit as authentic as the song — a block-party scene of Bobby, Rowdy, and the rest on the sidewalk, leaning up against parked cars, smoking marijuana, making gang signs, pantomiming shooting guns. The effect feels like a pure expression of urban teenage antics, a little menacing, a little goofy. Bobby stands out with a bright-white T-shirt and his blinding smile. Two minutes and 17 seconds into the three-and-a-half-minute video, he flings his hat out of frame and breaks into a long, slow, lopey shoulder dance. He called it the Shmoney dance. The video launched on the World Star hip-hop video site, but it wasn’t until June when a six-second Vine of Bobby tossing his hat and dancing went viral that Bobby Shmurda became a star.

By midsummer, celebrities everywhere were doing the Shmoney dance — Beyoncé, Chris Brown, a bikini-clad Rihanna. Jay Z name-dropped it. Larry King cameoed in a Shmoney-dance Vine. Dolphins receiver Brandon Gibson did a Shmoney touchdown dance. More than 3 million people ran the Vine in a matter of months. Pollard did what he could to play up the visibility. At BuzzFeed’s offices, he snagged someone’s scooter and started scooting around the office; then he put on a big green sombrero and went cubicle to cubicle, doing a Mexican dance. When TMZ showed him doing the Shmoney dance outside Sirius XM’s office, the YouTube had a second rally.

As the YouTube of “Hot Nigga” was catching on, the crews continued to clash. That spring, Pollard was taped talking about defending himself from rivals. “I am Two-Socks Bobby right now,” he said, “socks” allegedly meaning “guns.” In May, he and Slice were taped in a conversation in which a third friend reported someone trying to shoot at him. “Son, they scoomed me last night,” the friend said, adding that both of his guns, “tunes,” jammed. “You scooming too fast,” Slice advised.* Behind his back, Meeshie seemed concerned that Pollard was growing brazen and that no one in the crew wanted to call him on it. “They don’t wanna say it, but they don’t wanna tell Chewy nothing,” he said in one phone call, “ ’cause they, like, scared and shit.”

Sure enough, in June, just as the Vine was taking off, the police responded to a call of shots fired at a barbershop on Clarkson Avenue. They believe that Pollard shot over his brother Javase’s head during a squabble, shattering a glass window. No witnesses would confirm what happened. Two days later, narcotics cops arrested Pollard and several others at an apartment on Rockaway Parkway they believe was a trap house, a spot where gangs stash weapons. Police found an automatic pistol. Pollard and his friends were released soon after with the possibility of being charged later. His friends were taped saying it ought to be an easy charge to beat. They understood the legal defense of “constructive possession,” where if more than one person is found in a place with something illegal, it’s difficult to ascribe ownership to just one person. Or, as A-Rod put it, “You can’t pin a gun on two niggas.”

While police were investigating the incident, “Hot Nigga” was becoming the rap hit of the summer. (The radio version was renamed “Hot Boy.”) Pollard had offers to play shows all over the country and a host of major record labels trying to sign him. “I ain’t going back,” Pollard told Hot 97 host Ebro Darden on the air with Rowdy Rebel. “I’m tired of selling drugs. I don’t want to sell drugs. I’m tired of being in trouble. I’m tired of being on the block, gotta watch out for cops, and this and that. People get tired of that.” The DJ sympathized. Stardom had airlifted Bobby and Rowdy from the streets. “Music might be the only thing that’s gonna save those two young men’s lives.”

On the Fourth of July weekend, Bobby Shmurda had his big coming-out party, opening for one of his idols, Meek Mill, at the King of Diamonds strip club in Miami. A YouTube of Pollard, still a few weeks from turning 20, surrounded by strippers and his GS9 friends, seemed to fulfill the ultimate promise of “Hot Nigga.” A few days later, the indictment came down for the gun incident. Only Pollard ended up indicted, accused of holding the gun during the raid. Pollard’s lawyers say it isn’t true; as far as they’re concerned, this would be the first of many times the police would target Bobby Shmurda just for being famous.

For years, there had been rumors of a file the NYPD kept updated with names, home addresses, and telephone numbers of major hip-hop figures. In 2004, the Miami Herald got access to the dossier, a six-inch-thick binder, from the Miami police, which had borrowed it from the NYPD to keep tabs on P. Diddy and DMX and their entourages when they came to town. Soon after, the Village Voice reported on a special NYPD unit dedicated to hip-hop surveillance headed by a police detective named Derrick Parker, who became known as New York’s “hip-hop cop.” “The NYPD sees rap groups as gangs committing crimes, and they see the rapper as someone who has money and public influence,” says Parker, who has since retired and works arranging security for clubs and major events.

Coincidentally, Parker worked a few gigs where Bobby Shmurda and GS9 performed over the summer and came away convinced that Pollard’s celebrity brought him extra scrutiny. “The police really fixated on him and really wanted to bring down his organization,” he says. “That’s what I used to do. My objective was to bring down violent gangs and dismantle them. Because these small gangs, once they become big, the murders start, the drug dealing starts.” But just because Pollard was targeted, he says, doesn’t mean he wasn’t up to something. “The sad thing is, with Bobby Shmurda, he was part of this crew,” he says. “And this guy happened to break out with a hot record, but he couldn’t leave his gang ties alone.”

Back in East Flatbush, Rasha accidentally shot A-Rod in the shoulder during a July 12 gunfight in which a 22-year-old woman who had been sitting on her front porch also got hit by a stray bullet. Meeshie is said to have driven the car during the shooting and hidden the guns in his apartment afterward. “I don’t know how to say this, nigga — just Wild West shit,” Meeshie was taped telling Slice.

In interviews, Pollard was easing into his newfound celebrity. On Power 105.1’s morning show, he bragged about being at a strip club the night before, and when asked about what he saw in his future, he mentioned drinking with Diddy or playing golf with Jay Z. “I’m trying to be, like, the new 50 Cent,” he said in a separate interview with Complex. “I’m trying to do sneakers, some watches, some water. I’m trying to sell it all … I’m trying to do a movie with Kevin Hart.”

But Pollard needed help making sure his East Flatbush life wouldn’t derail his music career, even as it helped make his name. His mother consulted with Debo Wilson, a longtime boyfriend of her sister’s who runs a small Miami label called Hard Tymes. Wilson put together a management team for his nephew, including Jerry Bagley, a manager and event promoter who orchestrated all of Pollard’s media appearances. Even as the pressure from police mounted, Pollard played along brilliantly. “He was one of the most charismatic people I ever met, especially so young,” Bagley says. He also worked to keep Pollard’s gun incidents quiet while the rapper courted record labels, and for a while, at least, none of that stopped his ascent. The only problem, he says, was his friends.

Bagley put Pollard up in a hotel in Manhattan for a few weeks, but it didn’t work. He would cut away for days at a time, coming back at night to sleep. And his friends would meet him in the city. “We said to him, ‘Look, you can’t have gang members around.’ He didn’t listen,” Bagley says. “I just think that he was trying to help people out. I know Bobby was a good guy. He took care of his family, he took care of his friends, and wanted to look out for them. He wanted them to experience some of the stuff he was experiencing.”

The police kept close tabs on Bobby Shmurda’s local appearances. Donnie Flores, another early member of Pollard’s management team, remembers getting pulled over on the way to a show: “They found an old-ass little joint and arrested everybody in the car and he couldn’t do a show that night. When I went to the precinct to try to get him out, the police were playing his music. They were like, ‘Aw, we got him, Bobby Shmurda. I can’t believe my kid listens to this shit.’ ”

“At first I didn’t want to sign to no label,” Pollard tells me. Now he was changing his mind. “The cops kept bothering us, so we felt like signing to a label was gonna help us get out of the neighborhood more.” He took meetings with Rick Ross, Atlantic Records, RCA, and 300. Then Epic’s urban A&R man, Sha Money XL, offered Pollard a face-to-face meeting with L. A. Reid, the label’s chairman and CEO. Pollard walked into a boardroom and performed “Hot Nigga” and a guest-verse from a Rowdy Rebel track for a room full of executives. Reid said he wanted Pollard to sign without leaving the building.

The sticking point with every other label had been they all wanted just Bobby, not GS9. Epic offered Shmurda his own label under the Epic umbrella. Rowdy Rebel and everyone else in the crew would be separate artists working for Pollard. Bobby Shmurda would be CEO of GS9. In the middle, as Bagley recalls it, running the label would be his uncle’s company, Hard Tymes Records. Hours passed as he debated whether to sign. “Bobby kept going downstairs and talking to his friends,” remembers Flores. Finally, he agreed. They announced the deal on July 17. When the gun charge made news a few days later, Epic didn’t flinch. “No one does the underdogs better than me,” Sha Money XL tweeted. The deal was rumored to be seven figures; Pollard says it was $1.5 million.

Record deals are structured as advances on future earnings. So far, all he had was one song and a six-second Vine. Pollard set about making remixes of “Hot Nigga” and an EP and started cultivating a few solo acts like Rowdy. He also upgraded his wardrobe, wearing shades to every interview. On Power 105.1, he told DJ Angie Martinez about his new ride (a Mercedes-Benz Sprinter); mentioned firing his stylist (“I go from homie to homie — you fired today, you hired today”); and complained about having to work two gigs on his 20th birthday. Mitch was with him at the station, standing behind him, stone-faced. Pollard described Mitch as his minder. “He don’t smoke,” he said. “So he sober.”

Almost immediately, though, the pressure of his sudden success seemed to get to him. He began to suspect that Wilson and the people who worked for him were ripping him off. Venues would pay half their fees up front, and Pollard would wonder where the money was. “They booked, like, 20 shows, and each show was $5,000 to $10,000,” he says. “And when I came to my bank account, it was less than what the label gave me. It was less than the up-front money. I was like, That’s crazy. I think it’s ’cause I’m young, they think they can do anything and tell me anything.”

On Instagram, Pollard lashed out. “I’m doing all these shows not getting ma money,” he wrote. “Dey got me doing shit every fucking day … I ain’t got nobody to trust ain’t no help in dis bitch I’m ready to go back to da trap be4 jail.”

Wilson and his team all say that Pollard was paranoid and naïve — and that they never had any access to his accounts to begin with. “He was saying, ‘I don’t want to do this anymore, I don’t want to do the rap thing, people are stealing my money,’ ” Bagley says. Meanwhile, there was no money coming in. “He was missing interviews, he was missing engagements, saying, ‘I don’t trust the people around me.’ ” Several gigs were canceled, and some went on without him. “He was getting burned out because of the way that he was working,” Leslie says. On July 27, Fabolous brought GS9 out to perform “Hot Nigga” at Barclays Center in Brooklyn — without Bobby Shmurda. Rowdy Rebel rapped in Pollard’s place. In early August, as Bagley recalls, the president of Epic, Sylvia Rhone, sent an accountant to look at Pollard’s books. Bagley says they found no irregularities. (No Epic executive would comment for this story.) “The sad thing was when the gentleman looked at the money and saw everything and told Bobby, he says, ‘There’s nothing wrong here — every receipt, every transaction, there’s nothing wrong. Actually, you’re spending ridiculous amounts of money. You spent $7,000 this week alone. What are you doing?’ ”

“Everybody wanted a piece,” Donnie Flores says. “We were paying for a hotel every day in Manhattan. Everyone wanted to travel with him wherever he went. You have to pay for that. It was too much — too many friends back and forth.” Pollard says that Flores was one of the ones taking advantage of him. “Dizzy is sneaky,” he says. When clothing lines sent him free samples, he says, “he’d come over and he’d be wearing it already.”

Pollard wanted Hard Tymes out of his life. “My uncle sees success in me, and he tried to put his Hard Tymes with it,” says Pollard. At Manhattan’s Dream hotel in early August, he insisted that Wilson fire Flores and another employee. “I didn’t fire them, and he was upset I didn’t take his side,” Wilson says. “I said, ‘You can’t make allegations against people if they’re not true.’ ” Wilson left town. From then on, Hard Tymes was out — they’re suing now to get bought out of their piece of the deal with Epic — and Pollard worked directly with the label.

One sunny Sunday afternoon, Rowdy Rebel and another GS9 member, Santino “Cueno” Boderick, were driving on residential Dean Street in Boerum Hill, between Hoyt and Bond Streets, when they spotted a member of Folk Nation in another car. Boderick opened fire with pedestrians all around. No one was hurt, but the skirmish was caught on video.

Pollard was nowhere near this one. Gigs had taken him out of town — Tallahassee, Philadelphia, Indianapolis, Washington, D.C. In October, he performed on The Tonight Show With Jimmy Fallon. That same month, his GS9 friends got into trouble in Miami. Police say Rasha fired shots in a crowd, outside Fat Tuesdays in South Beach. A day later, they fired shots out of a car belonging to a PR executive who worked for Rowdy Rebel. Two weeks later in New York, police say, Rowdy’s little brother Remy fired a .380 in front of the Social Butterfly nightclub on Atlantic Avenue. Forensic tests matched the gun to the July shooting of the innocent bystander on the porch in East Flatbush.

In November, Epic released its first Bobby Shmurda EP, Shmurda She Wrote. Pollard also released an app called Shmoney Gram that allows you to upload any photo into an iconic Shmoney-dance moment. On Instagram, Pollard mourned the Eric Garner grand-jury result, wished Jay Z a happy birthday, and thanked his fans for making “Hot Nigga” platinum. He performed “Hot Boy” on Jimmy Kimmel Live, yelling, “Mitch caught a body ’bout a week ago” extra loud.

A week before Christmas, police armed with machine guns rounded up 13 GS9 members at Quad Studios on Seventh Avenue in Manhattan — the same studio where, 20 years earlier, Tupac Shakur was robbed and shot five times. The police cuffed five or six of them right away. Rowdy Rebel and Cueno both ran and hid; when they found them, they also found a bag stashed in the stairwell with three loaded guns along with a receipt from a hotel with Rowdy’s name. Pollard had slipped out of the building in the backseat of a car. They didn’t get far before police stopped the car and found two guns — one shoved in the seat between Pollard and a friend, the other in a duffel bag on Pollard’s lap.

After the raid, Leslie went to the police station to find out about her son. “When I went down to the precinct, they were playing the music and laughing, ‘Oh, we got him tonight — they’re not gonna do any Shmoney dance tonight!’ ”

“Hot Nigga” wasn’t a dance hit to them. It was a taunt. “The day they locked me up,” Pollard tells me, “they said, ‘We’re tired of our kids listening to your music.’ They said it to my face, laughing.”

The charges against Pollard included weapons possession, conspiracy to commit murder and to commit assault, and possession of drug paraphernalia. His charges were far from the gravest, but prosecutors still placed him at the top of the 74-page indictment that argues that Pollard and his friends conspired to sell crack and murder rival gang members. “There is no question that Ackquille Pollard is the driving force behind the GS9 gang,” prosecutor Nigel Farinha said at the December 18 arraignment, “and the organizing figure within this conspiracy.”

He and Rowdy Rebel were granted a bail amount of $2 million — which, in Pollard’s case, is about ten times what others have received for comparable charges. As James Essig, head of the Brooklyn South Violence Reduction Task Force that made the arrests, explained at the press conference, his song and video were “almost like a real-life document of what they were doing on the street.”

The lyrics of “Hot Nigga” weren’t formally cited in the indictment, and it’s doubtful prosecutors will use the song as evidence. But as his case makes its way toward trial in June, the question of Bobby Shmurda’s authenticity will become something for a jury to decide. Because prosecutors are claiming the multiple shootings and drugs and weapons busts are part of a sprawling conspiracy, Pollard doesn’t have to be the worst offender to be implicated and exposed in the activities of his fellow crew members. But to convict Pollard, prosecutors will still have to connect what he’s saying on those wiretaps to actual crimes.

Pollard’s defense lawyer, Kenneth Montgomery, says they’ve yet to produce evidence that Pollard did anything that suggested he was a ringleader — anything that shows him directing anyone to commit an act of violence, or discussing prices and weights with suppliers, or physically hurting or intimidating anyone. The whole supposedly criminal enterprise of GS9, he says, is weirdly lacking in crimes. “I want to see how much money they recovered,” Montgomery says. “These kids weren’t kingpins.”

Montgomery grew up in nearby Brownsville, and also represents the families of Kimani Gray, a 16-year-old shot and killed by police in East Flatbush in 2013, and Akai Gurley, killed by police in November. “I don’t think people understand the paramilitary stance the NYPD takes against these kids,” he says. He comes down hard on Epic, too, whose executives didn’t seem to mind when Pollard’s gun charge went public back in July. Now the label won’t pay the $200,000 for a bond to get him out before his trial. “It is quite off to me why they aren’t helping him,” Montgomery says. “But I guarantee once he’s out, they’ll be all over him, trying to make more money from him.”

“I’m innocent,” Ackquille Pollard says. His orange jumpsuit stands out from the gray walls of the Manhattan Detention Complex, his smile bright and white and flawless as ever. “I’ll explain it to all of them. I’m just a young black kid coming from a nasty neighborhood. I made it out, and a lot of people don’t want to see that.”

We’re talking over a video-conferencing link, usually used by inmates for conversations with their lawyers. Onscreen, he seems like a teenager still, too small for the jumpsuit. When he speaks, he sounds less street than he did during his interviews last year; he’s doing what he can to project confidence that he’ll beat the charges. “It was so crazy with the police,” he says. “There’s people with ten murders that got $500,000 bail, and I’m not even on an attempted murder.” He denies that being a rapper in GS9 means that he killed anyone, or sanctioned killing, or anything like that. “I’m guilty for where I live. I was never part of no gang. That’s just because of the neighborhood,” Pollard says, then hedges in a way that shows how elastic the term has become. “You don’t even have to be in the gang to be in the gang. You can probably just grow up in the neighborhood, you part of the gang already.”

We talk about his childhood — about Dondi and Tyrief and his father — and about his uncle and the money worries and the record deal. Pollard says he wants out of his contract. They wanted him because he was real. Now they don’t want him because he’s too real. “Epic is telling me it’s not because of them, it’s ’cause of Sony,” Epic’s parent company, he says. “But I don’t know. I felt like if I’d have signed with Rick Ross or signed to 50 Cent, they’d have come and got me. They’d understand me more.”

If he rose to fame on a hip-hop cliché, now he’s doubling down. He’ll be like Jay Z and Meek Mill and everyone he looks up to — creating a transgressive image, and then using the fame to absolve himself.

His time is up. The guard yells from out of frame. He won’t stop talking until the guard yells at him again. Instead, Pollard smiles broadly one more time, assuring me his future is bright. “I get letters in here from people with clothing lines, they telling me when I come out they’ve got a bunch of clothes for me,” he says. “Yesterday I got a letter from a movie director. He said he wanted to shoot a movie of my life.”

*This article appears in the May 4, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.

*This article has been corrected to show that it was an unnamed friend of Pollard’s who said in a taped May call that he thought someone tried to shoot him, not Pollard himself.