David Chase on the Legacy of Twin Peaks

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the debut of Twin Peaks, the influential ABC drama by David Lynch and Mark Frost that was a police procedural wrapped around a soap opera wrapped around a surrealist-expressionist nightmare. It debuted April 8, 1990, and ran for two seasons, and while ratings ebbed after the premiere, its singular style had an enormous and lasting impact. So much so, in fact, that Showtime plans to revive the series, with nine new Lynch-and-Frost-written episodes. (Lynch had originally been slated to direct as well, but pulled out of the project in April, potentially putting its future in jeopardy.) One of the showÔÇÖs biggest fans was David Chase, creator of the Freudian gangster drama The Sopranos. The HBO series drew on Lynch and FrostÔÇÖs imagery and tone. We spoke to Chase about Twin PeaksÔÇÖ impact on his own work, and on TV as a whole.

Seitz: Where did you first watch the premiere?

Chase: At home. I didnÔÇÖt watch a lot of network television at that time. I had had enough of franchises and police and judges and lawyers and all that. My daughter was about 8 years old, so I was doing a lot of parenting stuff at night, like playing Barbie dolls and reading or stuff like that. But I made time to watch Twin Peaks because it just looked interesting, and I was a huge admirer of Blue Velvet.

Seitz: What about Twin Peaks seemed new or different?

Chase: Well, I donÔÇÖt know how to explain this, but as surreal as Twin Peaks could be, and as particular as it could be, as it was, it felt more like real life to me than the average hour-long television show. It has always been important to me to feel the geography of a place. When I first went to work on The Rockford Files, they showed me three episodes of it, and I thought, Boy, that really is Los Angeles. ItÔÇÖs not just Los Angeles as someplace, itÔÇÖs Los Angeles. And that made me want to take that job. I really felt the same way about Twin Peaks, oddly enough. I thought: I believe this town out in the woods, in lumber country, in Seattle. Also, the show was visually beautiful, and I donÔÇÖt think a lot of TV at that time was.

Seitz: David Lynch was a painter before he was a filmmaker, which may account for some of that.

Chase: Oh, IÔÇÖm sure it accounts for almost all of it! I remember the colors of it. The colors of the roads were different, the curtains were different. Everything was. And while the show was very dreamlike, there was also something hyperreal about it.

Also, you couldnÔÇÖt tell exactly when it was taking place. You knew that it was taking place in the current day, which was 1990, but at the same time, it also felt like the ÔÇÖ60s, and that to me was miraculous. And the conversations, the speed of it, could be very laconic. I liked that, while I was watching it, I could have a somewhat spiritual feeling. Lynch calls it his unconscious, not his subconscious. But I think it goes right into the subconscious, and you feel that youÔÇÖve been there. ItÔÇÖs a sort of Jungian thing that he manages to hit.

Seitz: What do you mean by that?

Chase: When I say Jungian ÔÇö and IÔÇÖm really not an expert ÔÇö I mean the whole idea of archetypes and synchronicity. As human beings, we all have these things ÔÇö probably from our animal days, I guess ÔÇö that scare us, delight us. Lynch seems to go straight into that.

The shots of trees blowing in the wind, for instance. I mean, I donÔÇÖt think people had ever seen that on network television, just the trees blowing. ItÔÇÖs like: What the hell is that?

Seitz: I thought of Twin Peaks many times while watching The Sopranos, but never more so than that shot in season six of that very slow pan across the trees against the sky, with the branches blowing in the wind.

Chase: IÔÇÖd be very apt to say that shot was probably influenced by Twin Peaks, because I really did like that image. It was particular to The Sopranos, though, because of that one line we use in that season, the Ojibwe saying: ÔÇ£Sometimes I go about in pity for myself, and all the while, a great wind carries me across the sky.ÔÇØ

Seitz: I often sensed a kinship between Sopranos and Twin Peaks dream sequences. Like with the talking fish at the end of SopranosÔÇÖ season two: It seemed like part of a tradition that includes not just Lynch but filmmakers like Luis Bu├▒uel, who was a big influence on Lynch.

Chase: I would describe them both as surrealists, although theyÔÇÖre different artists. I wouldnÔÇÖt say we labored under their influence on The Sopranos, because the function of the dreams on our show was a little bit different. Tony Soprano was seeing a psychologist. The dreams were supposed to be interpretable. I donÔÇÖt think David LynchÔÇÖs dreams were like that at all. You have to remember, our main character is in therapy, and a big part of that is him talking about his dreams and fantasies with Dr. Melfi. The idea was to take what is mysterious and make it revelatory and pertinent. The dreams on our show were meant to be interpreted. But sometimes dreams were carrying the plot for us.

Seitz: That is one major similarity, now that you mention it. On Twin Peaks, dreams were often used to understand and, in some cases, to advance the plot. In fact, the first big breakthrough that Agent Cooper has is when he dreams about the dancing dwarf, and he calls Sherriff Truman to tell him heÔÇÖs figured out who killed Laura Palmer, and that, perversely, it can wait till tomorrow. But by the next day heÔÇÖs forgotten the killer and has to figure it out all over again.

I felt like maybe there were times when the dreams on The Sopranos were used so that they were not only giving Tony clues that helped him interpret things he had already experienced, but sometimes seemed to be foretelling things that would happen to him later. And isnÔÇÖt there a section in the season-five episode ÔÇ£The Test DreamÔÇØ where it feels like the real world and the dream world are intertwining?

Chase: Yes, they were! On The Sopranos, sometimes a dream was more plot-oriented, but other times it came straight from the subconscious.

I would say the most plot-heavy dream that Tony had was a dream state that was induced by food poisoning in which he realized that his best friend was his worst enemy, and was an informant. When you do something like that, youÔÇÖre actually plotting it out ÔÇö youÔÇÖre not, like, all of a sudden having a spark come from your subconscious. ItÔÇÖs more logical.

Seitz: How do you feel about the prospect of Twin Peaks doing more episodes?

Chase: I would be really curious to see a new version. Anything David Lynch does with Mark Frost, IÔÇÖd be there for that. I would love to see those two guys return to it, now that they had additional life experiences.

*This article appears in the May 4, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.

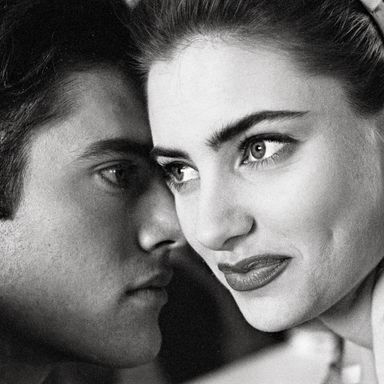

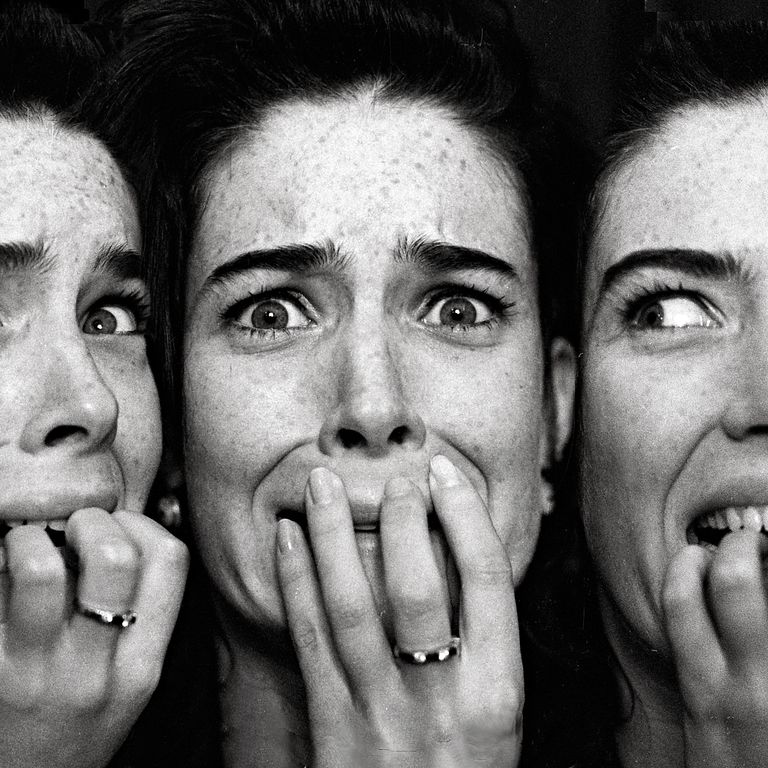

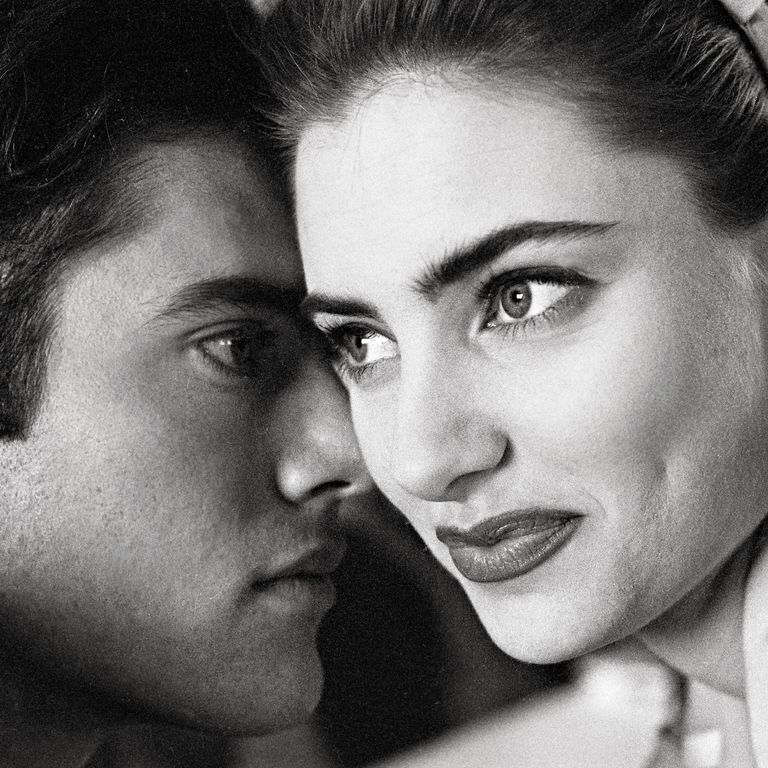

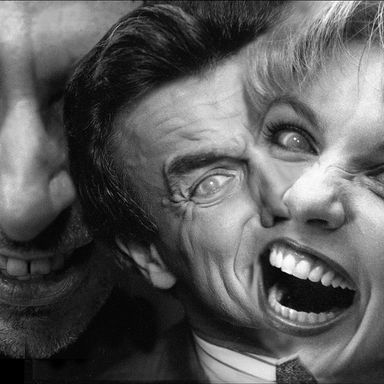

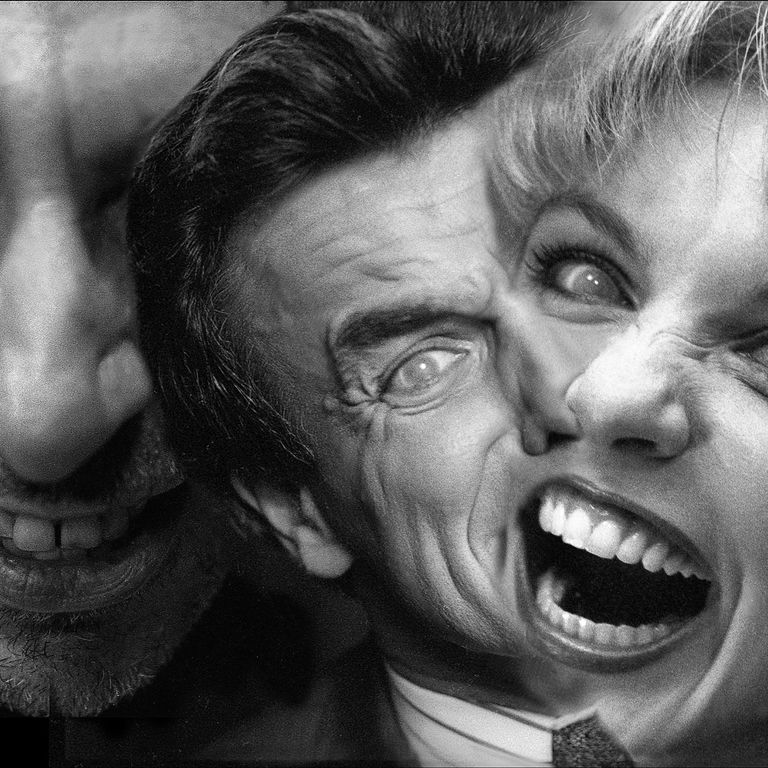

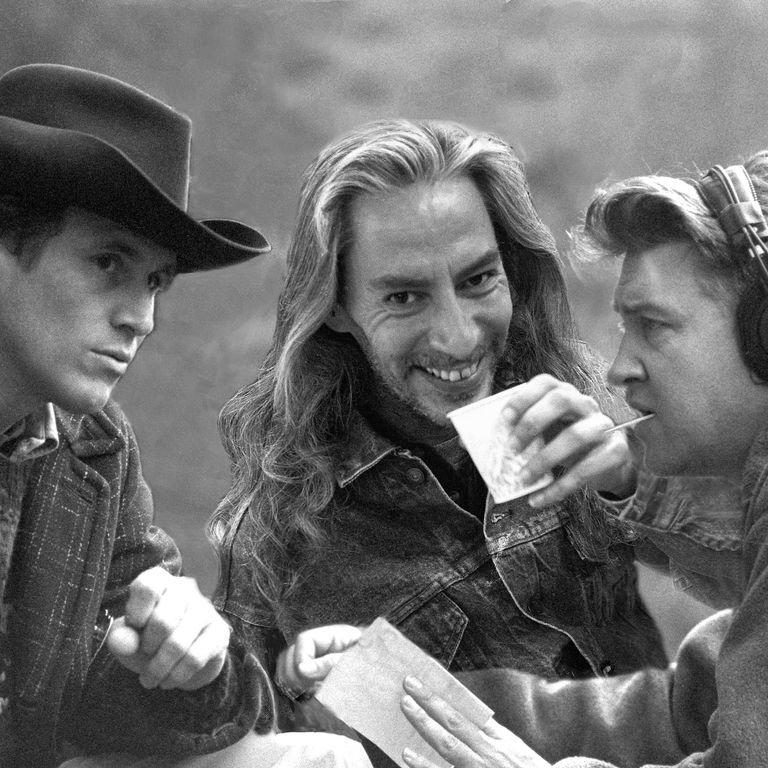

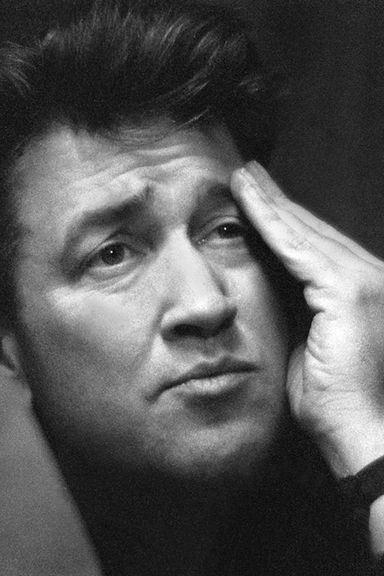

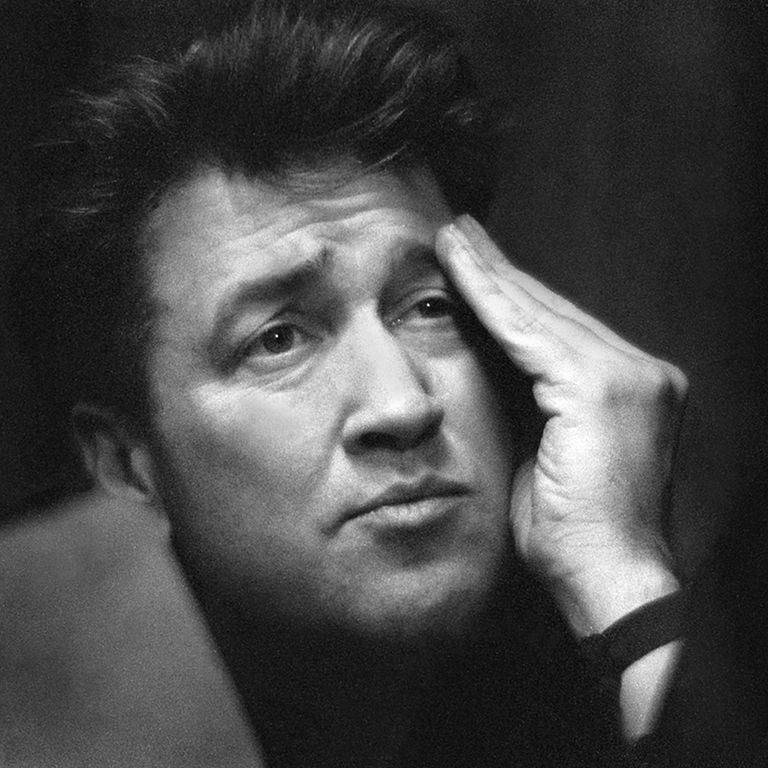

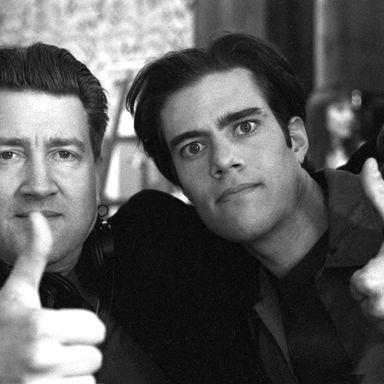

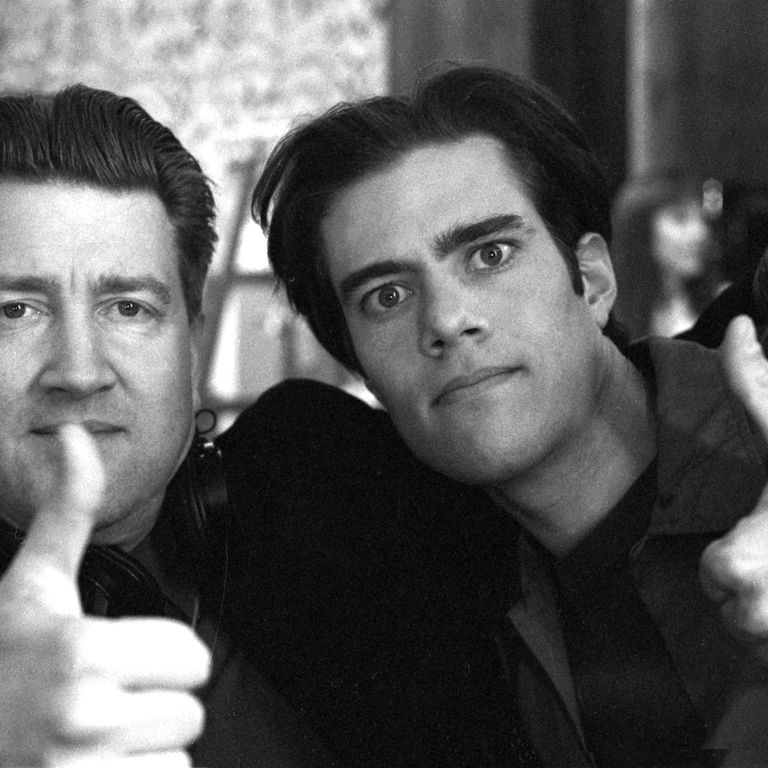

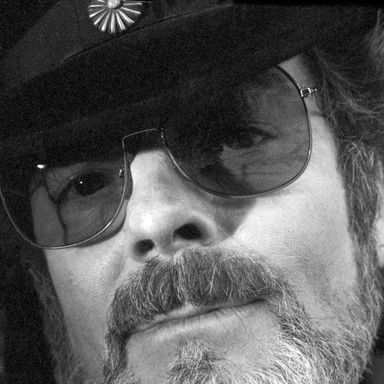

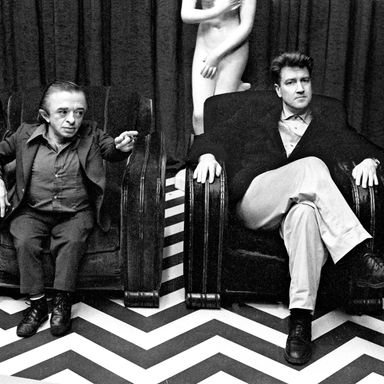

Click ahead for a gallery of photographs by Richard Beymer, who played Benjamin Horne on Twin Peaks, from the last week of filming.

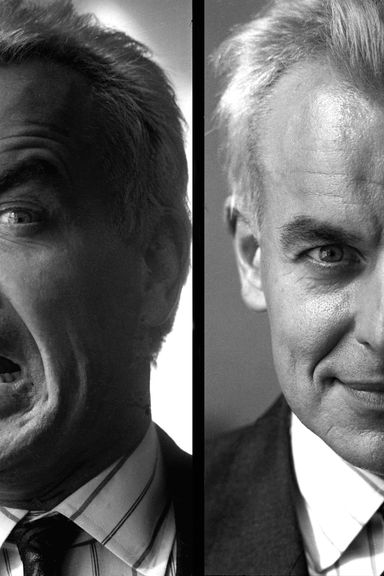

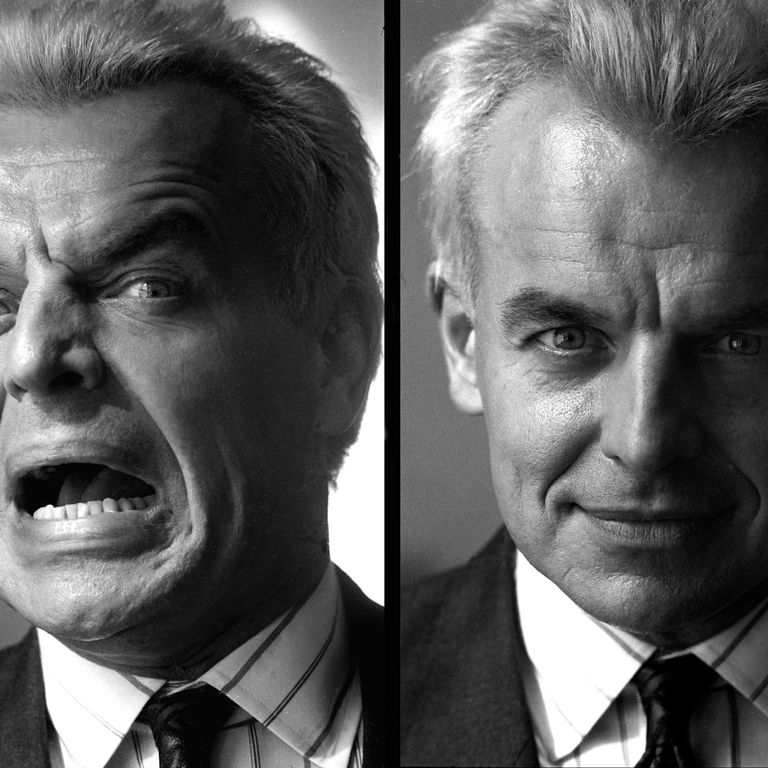

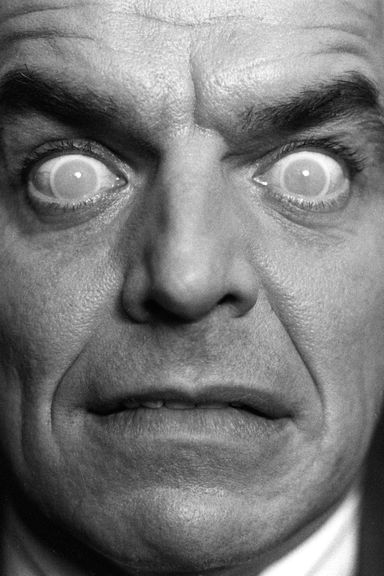

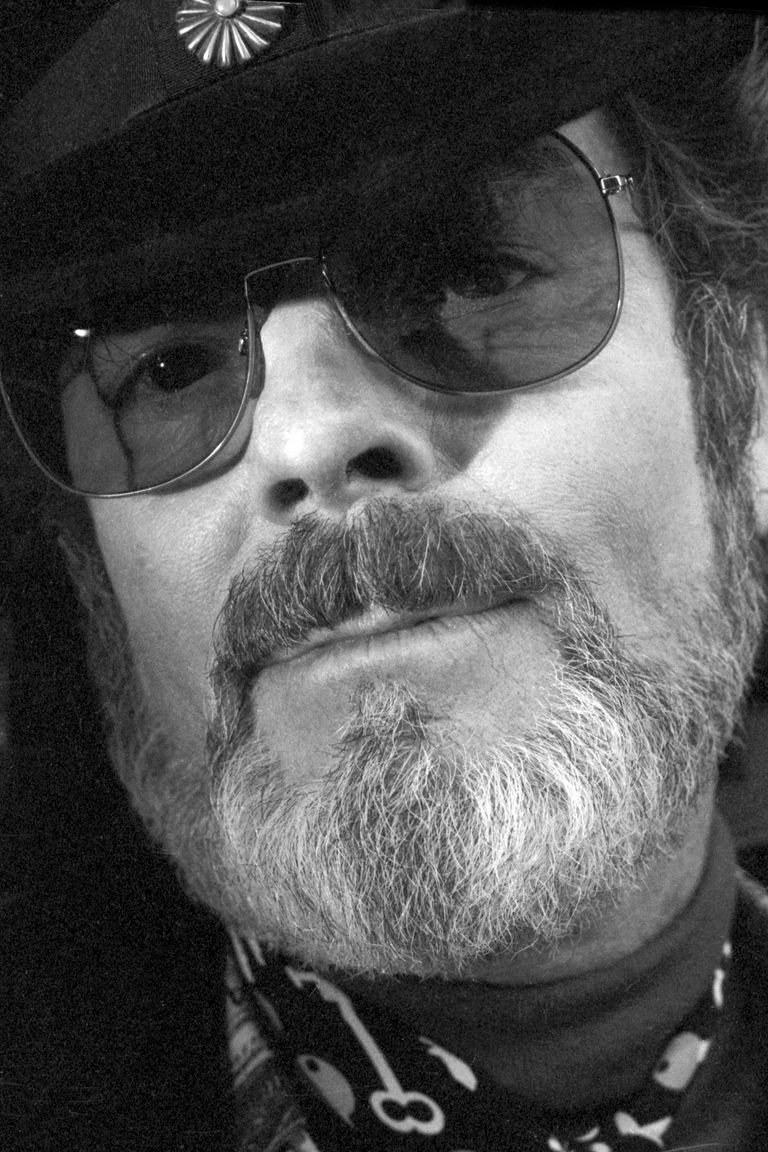

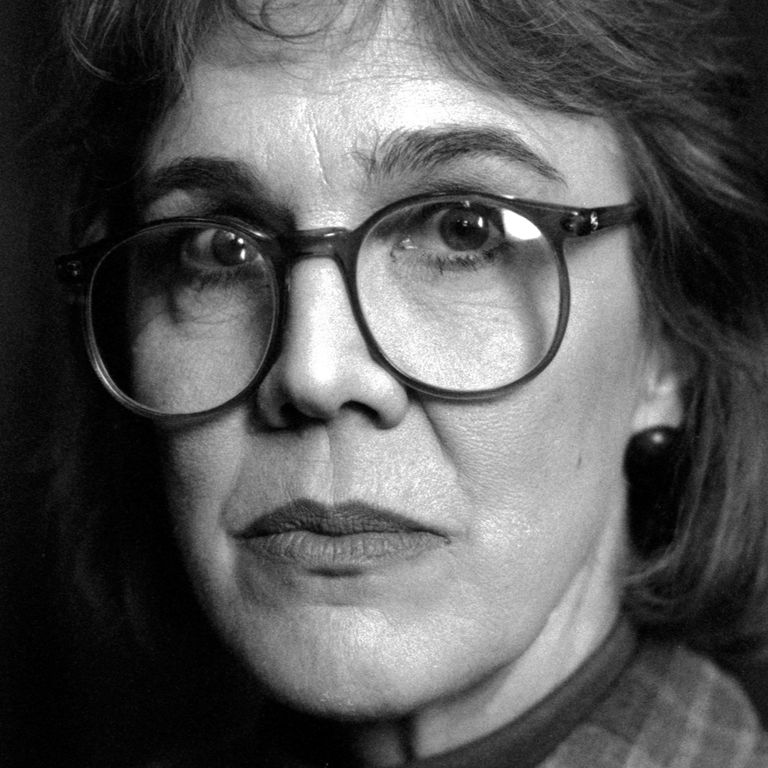

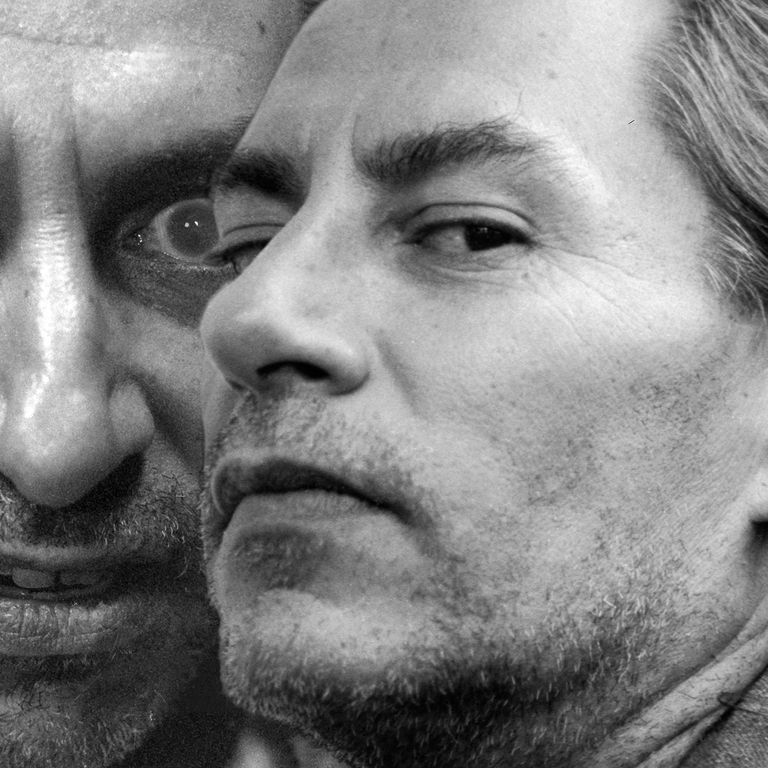

Photographs by Richard Beymer, who played Benjamin Horne on Twin Peaks, from the last week of filming.

Photo: Richard Beymer

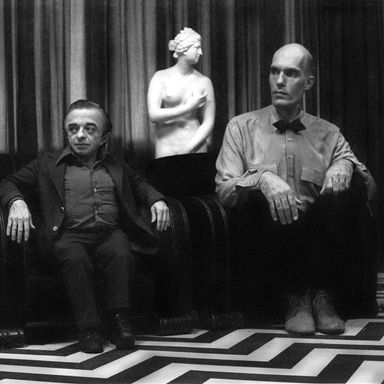

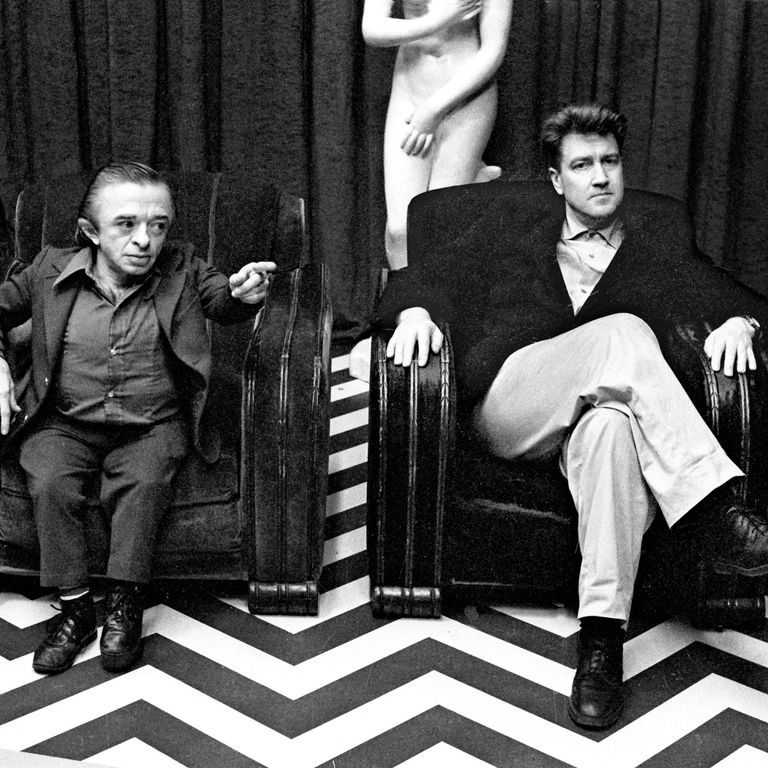

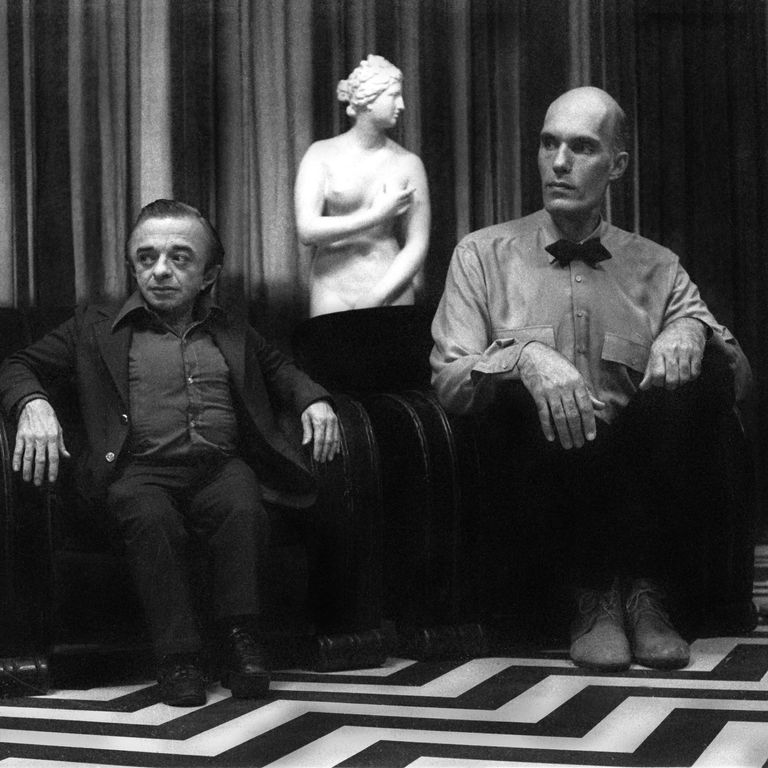

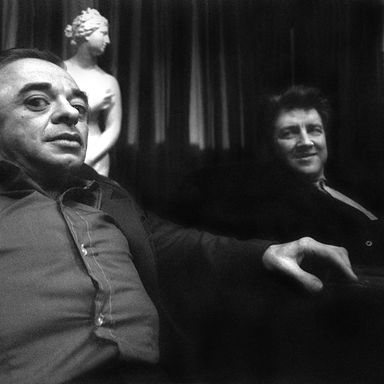

Michael J. Anderson and David Lynch on set.

Photo: Richard Beymer