Athens is a paradoxical megalopolis that brings together, amid the concrete and the clay, some kind of European bygone sophistication, a mild Mediterranean softness, and the most anarchic third-world chaos. Resting upon a very delicate and precarious balance, it has been, for more than five years now, deep into what we perceive as the “Crisis.” That word itself is now so bandied about that it is practically empty of any substantial meaning: Treated like a JPEG image or a hashtag, it is at best a godsend for headlines and more generally a cathartic outlet for the rest of Europe, turning into a flat stereotyped concept more than a conductor of the complex local reality.

From recession to austerity measures and riots, Greece is being swept by a financial tumult that drags along a continual social and humanitarian washout. Usually the art world is perceived as a sort of fallback spot, where the wind is softer and the waves are smooth. As a matter of fact, it is not anymore, the “poor but sexy” myth is slowly and surely crumbling, leaving Greek people with not much more than their offbeat, witty dark humor — probably the last life buoy and an act of moral resistance to the current and long-lasting situation. The gift shop of the new Benaki Museum annex in the Gazi neighborhood of Athens is selling “Fuck crisis, Let’s dance” tote bags. Silver printed on a sailor-striped blue-and-white fabric, the motto is both a self-deprecating fetish and a catalyst of the romanticized preconception someone might have from outside the country.

The Blow Job Index …

Our first visit to Athens this year started on February 14, following an invitation and frequent informal conversations with collector Dakis Joannou, an unrivaled cornerstone of the Greek and international contemporary art scene and longtime partner in crime of one of the writers of this diary. The taxi ride from the city’s Elefthérios Venizélos International Airport was frequently interrupted by the driver explaining in detail how to avoid anti-government protesters heading to Syntagma Square.

Immediately upon our arrival, curator Nadja Argyropoulou took us straight to a Dionysiac celebration of Valentine’s Day and a deep exploration of the rites of Greek Saturday nightlife. We started with a drink in the trailblazing Metaxourgeio neighborhood, which maintains its strong avant-garde credibility owing to the explicit activities of drug dealers and prostitutes. Among the dinky brothels stands the Breeder, which is one of the most trendy Greek galleries and an international art player representing mostly young Greek artists.

“We might be turning into a Kunsthalle soon,” said dealer Nadja Gerazouni, half in earnest and half in jest, while she gave us a tour of the three-floor space (with a restaurant) where they were installing artist Angelo Plessas’s solo show. “No one is buying in Athens anyway, so why bother?”

It wouldn’t be the only time that we’d face this feverish feigned nonchalance as a sign of despondency, tinged with a sincere will to keep things moving.

And the nearby brothels didn’t seem to be doing much better. On our way out of the Breeder, dealer and gallery founder Stathis Panagoulis took us for a brief exploration of these neighboring establishments (to which we dared to venture for pure monitoring and conscientiousness purposes). We were struck by the competitive rates. Like the Big Mac Index used by economists to compare standards of living, the blow-job rate can be quite an efficient informal way to measure purchasing power parity: After all, like the Big Mac, it is available to a common specification in many countries with a consistent theoretical price.

While watching, a flock of men carrying red roses kept entering the small, lined-up pleasure houses; we decided to skip the special Valentine’s transsexual cabaret that was the talk of the town. Instead, we went straight to the historic commercial triangle neighborhood where the Callas Studio (an artistic factory initiated by the brothers Lakis and Aris Ionas) was hosting a concert. The restless crowd was au rendez-vous in that tiny fourth-floor apartment, which turned into a smoke-filled artistic hot spot for the night. Some were expecting a special appearance by former Sonic Youth member Lee Ranaldo, who is writing the music for the new film of the Ionas brothers. Soon, all eyes were gazing upward: The Callas had organized a rousing but welcome group show where all the pieces were hung from the ceiling. “Hang’em High” featured works by Panagiotis Loukas, Nikos Kanarelis, Natasha Papadopoulou, and Tassos Vrettos, among other artists. The crowd was an enjoyable shuffle of artists, curators, gallerinas, musicians, film directors, and art students (including members of the Documenta team preparing the 2017 edition in Athens; Vassilis Zidianakis of Atopos; and Poka Yio of the Athens Biennale).

Fueled by a few two-euro beers and exhilarated by the ebullient vibe, we dragged artist Vassilis Karouk with us and our little contingent set off for a night of wiggling within the busy streets and the packed bars of the city, among masses of young people inhabited by what we perceived to be a compulsive need to seize the day.

We eventually ended the night at Six D.O.G.S., a merger of four bars that’s become a trendy hangout for Athens music aficionados.

The New Berlin?

In 2011, the New York Times ran a story titled “Greece’s Big Debt Drama is a Muse for its Artists.” The idea was that there was a burst of artistic activity in response to the national identity crisis. Inexpensive living and a laid-back lifestyle made Athens “artist friendly” and in pole position to threaten to take the “cool” trophy from an increasingly gentrified Berlin.

“The Greek art world has become much more active in the past few years,” says Elli Kanata from Elika Gallery. “Due to the crisis there is an urge to create, to express, to collaborate, and to address social issues,” as if the unrest opened a whole new spectrum of opportunities and an urge to invent creative alternatives to a state of bankruptcy. (This under-girds the legend of the New York art scene in the 1970s as well, of course.)

And visiting galleries and art spaces, we couldn’t help but notice a strong spirit of collaboration as well as a very efficient tendency to foment bottom-up projects with no funding.

We dropped by the up-and-coming Q Box gallery, located in the “Art Tower” of the Central Food Market, among the fresh olive booths and the fish counters. It was hosting a solo show by young artist Paola Palavidi. We wondered how such a young, dynamic gallery supporting mainly emerging artists could actually survive. “I never counted on public money,” explained gallery founder Myrtia Nikolakopoulou. “My network abroad is very supportive.”

The collapse of all the mechanisms support from the Greek government and the European Union has led to an outbreak of non-hierarchical and self-organized art collectives, popping up in often ephemeral locations. “Nowadays, to see an art show, you don’t necessary have to visit a gallery,” commented Panayiota Theofilatou and Tassos Papaioannou, founders of the nomadic Athens Zine Bibliothèque. “There are art shows everywhere, from artists’ houses or studios to coffee shops and public spaces. Greek art freed itself.”

“An interesting double bulimia can be observed,” Argyropoulou noted. “Lots of art and lots of food-related new spaces everywhere. Few will probably survive.”

Actually, several spaces we’d been planning to visit had already closed their doors.

“Some dynamic art galleries like Gazon Rouge, the Appartment, AMP, Els Hannape Underground, Xippas Athens — to name a few — closed down, changed form, or moved elsewhere,” said Christina Androulidaki, who owns CAN gallery, where we visited the Konstanstinos Ladianos solo show.

Helena Papadopoulos fulfilled the gallery-turned-Kunsthalle prophecy as she closed her Melas Papadopoulos Gallery and founded Radio Athènes, a nonprofit organization offering exhibitions, talks, and lectures in various pop-up locations she manages to find. We saw Kostas Sahpazis’s beautiful solo show, which she organized in the former office space of a neo-classical building on Apollonos Street in Plaka. Papadopoulos seems to be having fun: She has more freedom and a much clearer will to experiment without the commercial pressure of a proper gallery.

Family Matters

These nonprofit initiatives aren’t only a fallback solution to a commercial meltdown. Some were created from scratch by collectives of artists, curators, and several committed art players, and arose like an expanded version of the Greek family. They’re a kind of primary cell of solidarity, making up for the government’s deficiencies, which in any case is a very ancient split (didn’t Sophocles raise that family versus state antagonism with Antigone already?).

Families are inevitably about eating food, too. We attended the eye-opening and bountiful benefit dinner co-organized by two nonprofit organizations: State of Concept, a nonprofit gallery founded by Iliana Fokianaki, and 3 137, an artist-run space created by the younger-than-Jesus trio of artists Paki Vlassopoulou, Chrysanthi Koumianaki, and Kosmas Nikolaou. The dinner, described in the invitation as a “paradoxical ceremony celebrating carnal lust and the separation from death,” included among its sponsors was a local funeral services company.

Artist Maro Michalakakos conceived the party as her own funeral and displayed a plaster version of herself full of delicious and sacrilegious Koliva (a ritual food made of boiled wheat, almonds, ground walnuts, cinnamon, sugar, pomegranate, and other sweetnesses), used exclusively during funerals and memorial services. The 20-euros menu included bread baked by one of the curators, sautéed cuttlefish prepared by one artist’s mother, homemade lemonade, and a dessert as explicitly sexual as mouthwatering offered by pastry chef Stelios Parliaros. Suffice it to say, the situation had nothing to do with the usual one-month-rent costly and slightly dull institutional benefit dinners. Despite the funeral theme, the party felt more like a cozy wedding with close friends, family, and delicious homemade party favors.

As one might imagine, these grassroots fund-raising extravaganzas are not sufficient to keep a business afloat. The Greek art world also counts on its Godfathers, as all families do. They often discreetly appear under short elliptical names like “NEON,” “ONASSIS,” or “NIARCHOS” but are actually led by powerful and committed outsize collectors or families who remain somehow immune to the flailing economy. Notwithstanding the many differences between these various benefactors, as well as their international standing, the local art scene is their godchild. They take a thorough interest in its upbringing and development, standing at the ready should anything happen to the parental figure of the State.

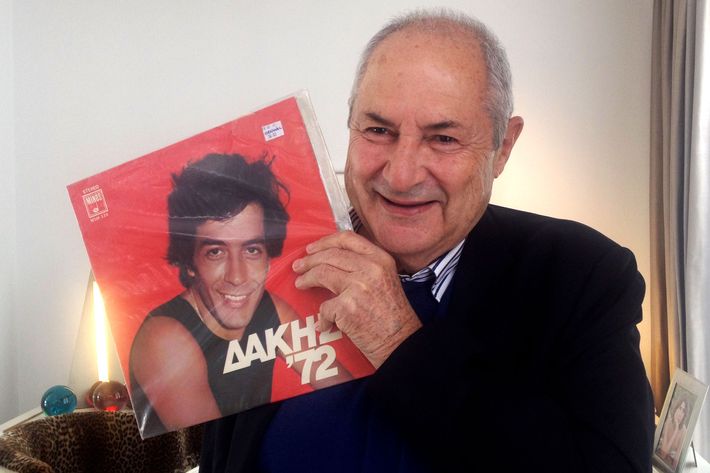

Dakis Joannou’s Deste Foundation is prominent among them. Someone once wrote that “Joannou’s distinctiveness stands in the fact that he doesn’t collect art to flatter his ego or because it’s a good investment. He does it for fun, and takes it seriously.” He does take it seriously: Not only does he support artists through his own private collecting, but he also takes part in keeping Athens’s institutions invigorated during this time of “crisis.” Deste is initiating a multifaceted program with the Cycladic Art Museum and the Benaki Museum this summer. Kim Gordon’s exhibition will open at the Benaki’s main building, while Roberto Cuoghi will hunker down at the new Pireos Street annex (with Ametria), showcasing works and objects from the abundant Benaki collection.

The annex will also host the Family Business gallery (now closed, but formerly in West Chelsea), which will feature a series of rotating exhibitions generated through an open-call system. Meanwhile, Nikos Navridis will present “Breath” at the Art Athina Fair, an installation inspired by Samuel Beckett’s 1969 play of the same name.

The Deste prize nominees will also exhibit at the Cycladic, continuing the foundation’s policy of supporting and promoting contemporary art in Greece. The prize aims to identify and showcase the work of an emerging generation of contemporary Greek artists who are actively redefining the parameters of cultural production and contributing to new issues in the artistic discourse.

The Art of the Crisis

One of the prize’s nominees, Socratis Socratou, was showing while we were in town: “Six Open Gates and a Closed One” consisted of new cast-bronze sculptures referring to the National Garden in Athens — nature ordered, transplanted, and delimited. The garden has, for Socratous, political parallels: It is an allegorical microcosm of current Athenian society — native Greeks living alongside recent foreign migrants. Depending on one’s point of view, this new (bio)diversity can be seen as an enriching element of multiculturalism, modernity, and progress or as an economic and cultural threat.

Socratou wasn’t the only one attempting to tackle, with a smooth subtlety, the Greek situation. Kostas Sahpazis at Radio Athènes presented visually strong sculptures made of leather, resin, plastic, rubber, and wires among other decrepit industrial materials, and worked on the creation of forms made up of totally unstable, changing parts, held together by a fragile balance. On a different and yet parallel note, Pantelis Chandris displayed delicate Mylar-foil installations at Elika Gallery, emphasizing a moment of oscillation of the human condition.

Without falling into some cliché of a sort of “compelled arte povera,” one can’t help but wonder about the existence of an “art of crisis.”

“I think art should always be ‘of crisis,’” argued Nadja Argyropoulou, “when a label such as this pops up, then you know we are in real trouble.”

But others are quick to claim it: “I could consider each artist who is active in Athens during this period as a representative of the art of crisis,” says Sahpazis. “This is a war situation without bombing! It would be unimaginable for artists not to respond to the situation,” says Roupen Kalfayan, director of the Athens- and Thessaloniki-based Kalfayan Galleries.

Consciously or not, artists are indeed appropriating the visible signs of the outbreak. “It would be interesting to identify the characteristics of this,” continued Sahpazis, “beyond any intention of each to express it or visualize it consciously.”

Some works made BC (before crisis) also look different within the current context. We visited Eftihis Patsourakis’s studio and, though we knew already his Headless family portrait series, some nostalgia surreptitiously and unexpectedly overran our perceptions of it now. Patsourakis paintings are a time game: They reintroduce temporality into forgotten family snapshots taken in the ‘70s and ‘80s. Besides the works themselves, the economic downturns changed the conditions of production, and they no longer feel like they’re related to any sort of market bubble.

“The crisis provided a good opportunity to focus on a less commercial and more experimental program” added Elli Kanata. The decrease of commercial pressure seems to have brought some focus in artistic practices for a less commodified and more socially engaged body of work tinged with a sense of urgency.

No Country for Young Men

Argyropoulou, who had curated “Hell As Pavilion” at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris back in 2013, touches indeed upon the underside of the romanticized expectation of an artistic salvation as part of an increasingly hazardous “folklore of disaster.” “Having made the choice to be based in Athens, I am practically unable to travel and research by now. Unfortunately, this has become a blunt norm of less. Exhibitions are very hard to make, many artists struggle to survive, and, worst of all, life is becoming impossible for most of the people around. Anything romantic you will hear about it will come from people who are not really based in Greece.”

In 2014, Greek curator Katerina Gregos organized a show titled “No Country for Young Men” at the Bozar Museum of Brussels. The title, which plays on Joel and Ethan Cohen’s film No Country for Old Men (2007) and the book by Cormac McCarthy of the same name, evokes the unfavorable situation for young people in Greece today and grasps both the disastrous repercussions of the hardship and the creative resistance it produced. The sense of experimentation the crisis brought doesn’t allow artists to make a living. “The local market has collapsed and the majority of mid-level collectors has disappeared,” noted Roupen Kalfayan, joining the ranks of the crisis-weary.

A few weeks after our trip to Athens, we met artist Maria Papadimitriou in front of the Greek Pavilion at the Venice Biennale, where she re-created a small taxidermy shop from the central Greek town of Volos. “The Greeks are idiots — this is my opinion,” she started in a feigned provocation. “We are living a moral drama … When you have no idea about the future, you also forget about the past.”

Papadimitriou wasn’t really in the mood for dancing the crisis away. “There is a beautiful and almost untranslatable Greek word which is far better to describe the mood,” stated Argyropoulou. “Harmolypi, roughly meaning ‘mournful joy.’”

In 2004, all eyes were on Greece for the Olympic Games. The whole world had hopes and wished for broken records and national performances. Today’s financial and political situation dragged another gaze, full of a will to rethink the future of the country and reverse the cataclysmic financial performances. As an introduction for his show “Hippias Minor” at Deste Project Space this summer in Hydra, Paul Chan uses a beautiful incantation: “A breath that unites contraries is what one is always looking for.” It is definitely what Greece is looking for. Might art fulfill the wish.