A conversation between senior art critic Jerry Saltz and editor David Wallace-Wells about just what to make of Kim Kardashian, her sort of brilliant book Selfish, and the weird fact that all of a sudden, everyone seems to be taking her very, very seriously.

David Wallace-Wells: Jerry, last year you wrote a fascinating essay about Kanye West, Kim Kardashian, and the “new uncanny” you detected both in their weird music-video project “Bound 2,” and also in their weird behind-the-bell-jar life as celebrities. Mostly, people mocked you for it. Last December, we published a derisive post about Kim showing up at Art Basel — “Kim Kardashian Thinks Her Ass Is a Work of Art” — which was a huge hit because it mocked her. When she announced she was publishing a book of selfies with Rizzoli, there was another round of mocking. But a couple of weeks ago, Kim actually released that book of selfies. And — well, have you seen the book?

Jerry Saltz: Yes, I’ve been savoring it. Like seeing a mystical life unfold right in front of her eyes. Now ours, too, in spite of so many people hating on it for so many years. Weird.

DWW: I want to talk about the book, for sure, but I’m actually more interested in the way the book has been received, which seems really meaningful to me.

JS: Meaningful, how?

DWW: Well, to be fair, the response hasn’t been universally rapturous. But there was, actually, a lot of rapture. To take just two examples, Laura Bennett called the book a masterpiece in Slate, and in the Telegraph, Sam Riviere called Kim a feminist artist who belongs alongside the Brontës, Jane Austen, and Virginia Woolf. Just this week, The Atlantic declared, “You win, Kim Kardashian.” A year ago, those were exactly the kinds of writers and the kinds of outlets that deployed Kim as a punch line about the end of culture. That’s a pretty incredible turnaround. Especially because, frankly, I don’t think Kim has changed very much.

JS: Completely. I sometimes think one of the reasons we get along is that we believe Kim. And you really are the only other literary writer who would refer to any positive reception of her book as “really meaningful to me.” Last year, when I wrote about Kim and Kanye, I said I was “struck dumb” by the “collective cultural fracturing” that they actually seemed to be engineering, and doing it with the blatant biraciality of their combined meme, and with grandiosity, sincerity, kitsch, irony, theater, and ideas of spectacle, privacy, fact, and fiction. All that had compressed into some new essence, an essence that they seemed to be shaping as surely and strangely as Andy Warhol once formed his. As with Warhol, this shaping simultaneously shines, shields, and spawns knee-jerk criticisms of crassness, shallow opportunism, and surface-only illusion. But it makes people look at the same time.

DWW: But no one else saw the same things, really.

JS: To me, it felt as if the art world was either being defensive, frightened, or hadn’t caught up to the disturbance in the image force. Regardless, the art world wasn’t having any of it; just the idea that Kim and Kanye could be creating something as out there as an aesthetic of a “new uncanny” or Andy-ish got people’s panties in a real twist.

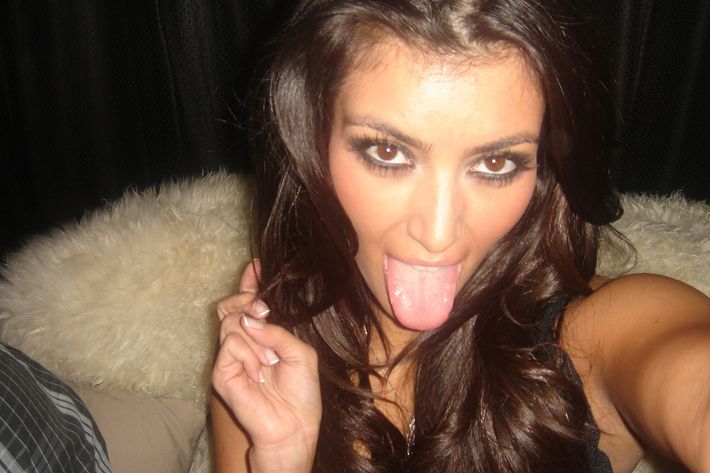

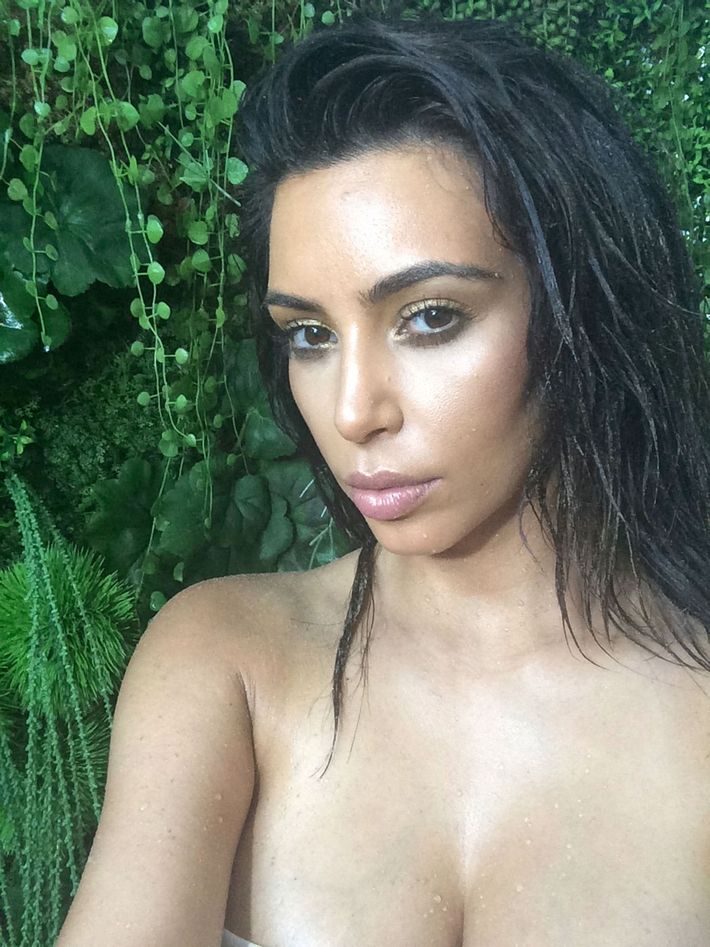

Now Kanye has gotten an honorary Ph.D. from the same art school that gave me one. I mean, how freakish is that! (Though, needless to say, many in the art world have protested this, too.) And Kim is now a role model. And she should be. She started taking selfies in the mid-1980s with pre-digital cameras, and many of the genre’s formal earmarks are already present in her pictures: the odd angles, arm holding the camera visible, peeks behind scenes, the fish-eyed distortion in the depth of field, the urge to create reality by documenting it. The irretrievability of passing moments.

She was enamored of her own form. We don’t even discuss how unconventional her form is and was at the time, given the rigid strictures of female beauty defined by society! And no one ever factors in the incredible freakish distortion of the social space around her as she was growing up: Her father, Robert Kardashian, was the defense attorney to and friend of O.J. Simpson! Either way, Kim was way out in front of photographic and media presentation that by now are a form. Accepted by the art world or not.

DWW: About that body: It was amazing to see, just a few months after Kim was derided online for joking that her ass was a work of art, a series of think pieces coming out of the Met Costume Institute gala celebrating sheer fabrics and declaring the body a worthy work of art (and the gym the new couturier).

But let’s leave aside — for now, anyway — the interesting way we’ve come to celebrate as feminist the sexualization of ampler female bodies (which suggests the crime against women by media over the past decades has been about bad body image, not pulverizing sexualization).

Kim’s book got me thinking about how these things change more generally — how something, or someone, that is considered beyond the reach of good taste and judgment becomes worthy of the attention of people who flatter themselves as serious critical thinkers. I don’t just mean professional critics, especially since there aren’t many of them anymore. But the people who think of themselves as intelligent consumers of culture — people who want and like to have opinions about music, movies, television, etc. To me, these are also people who — and here’s what I really want to talk about — seem more and more to depend on a kind of permission-giving consensus about a subject before they actually feel comfortable endorsing or even entertaining it. With so many subjects, there seems to be a sort of tipping point, followed by a flood.

JS: What else are you thinking of? Because you probably already have a lot of these “critical thinkers” thinking you’ve simply joined them in the populist gutter.

DWW: Well, just for instance, take television: Okay, yes, sure, TV is definitely better than it was ten years ago. But much more striking to me than the difference in quality is the difference in seriousness of attention paid to it. It went from being something a lot of self-serious people were uncomfortable getting excited about to more or less the only thing they talk about with each other. Is that just because Louie is better than Freaks and Geeks, or because Mad Men or The Wire are better than Homicide: Life on the Street? I’m biased, I know, and probably crazy, but I don’t think they actually are better — probably another conversation for another time.

But what’s changed undeniably is our attitude towards television, which has allowed a lot of people who had sort of trained themselves to deride it to finally allow themselves to enjoy it. We are so much more open to quality now, and pleasures of the form like seriality, character familiarity, and immersive narrative. And because we’re more open to it, we see quality more.

To me, there’s definitely been a similar shift with the Kardashians, especially with Kim. What do you make of all that, as an actual, professional critic? There’s a pretty conventional idea of that job as a sort of lone intelligence, making independent judgments and (when the critic is a good one) pointing readers to exciting new things they wouldn’t otherwise discover or appreciate or understand. But it seems to me, especially when thinking about someone like Kim Kardashian, for the most part, they are riding waves much more than they are charting new paths.

JS: Boy, are you making a couple of big points. First: As a critic, I’ve always believed that everyone is a critic, that there’s no absolute objective standard to art or music or all the rest. That it’s all a matter of taste. With social media spreading the critical virus now, we’re all critics out loud, idiots or not. The more people call things the way they see them, the better. Although I wish everyone would work with an editor.

Which leads to the problem with all that: People don’t really call them the way they see them at all. They call them the way other people have already seen them. Or the way they think they should call them. Fear and cynicism are now ingrained into the system. Fear of being wrong — not just wrong alone in your apartment or in the face of a few friends the way I was in 1977, when I was sure punk was bad. Now we are wrong in public. With instant feedback loops forming, opinions are now had before we even know what we really think; we’re only knowing what we’re supposed to think and then thinking it. I see this in the art world often. Cynicism is used to deflect any criticism at all and shrouding opinion in certitude. I hate it.

DWW: There’s been a lot of talk in the social media era about the end of authority — how networks of friends, say, have replaced experts, and Yelp taking over for food critics. That’s definitely part of what’s happening here with Kim, and so it’s tempting to see the phenomenon as sort of democratic. But I can’t help thinking the opposite is also happening — that we haven’t been liberated in the way we think about some cultural product or other, we have just learned to defer, just as totally, to a different authority — some sense of conventional wisdom. Which makes me wonder: What do you think it means that it’s now a kind of conventional wisdom that Kim is someone worth thinking seriously about?

JS: Here’s where it may start to get really interesting. What might it mean that collective critical thinking, such as it is, in this case, the acceptance of Kim not as a freak show, huckster, or something sold, but instead as something self-created, self-aware, and sincere, with its own essences and vulnerabilities.

I think that we may be turning a corner away from what I think of as takedown culture. Of writers, commentators, critics, or those in authority taking to the airwaves or wherever and laying people low, grousing, snipping, passing all sorts of extraordinarily general disparagements of whole professions or trying to take someone out altogether. It all comes from cynicism, the feeling that the system is corrupt and that everything is rigged and nothing is what it seems. We all love a good critical catfight, but somehow, with these catfights and cynical demonizations becoming the way of mainstream media, I perceive the wider culture and the art world slowly trying to separate out and isolate this behavior for what it is: Headline-grabbing, grandstanding, gasbags, people scared of change, or afraid of going deeper. I saw a critic review the entire NADA art fair with two words: “I’m disappointed.” Other critics duck the issue altogether, preferring instead to just gripe about what another critic says. We have so many people using their energy now to attack how other people use their energy. This is the new nullity.

In the art world, two or three generations of critics were all but lost to academia or having the subjectivity and original opinion scared out of them, making them refrain from writing clearly, with voice, judgment, something personal. That’s changing. Fast now. I see a whole new generation of younger critics unafraid of all those things. A homegrown, unafraid criticism is springing up in the wreckage of criticism that is still mostly conventional wisdom with right and wrong artists, -isms, attitudes, tastes, and all the rest. I mean, Kim has nothing to do with it, but the ethos of acceptance or change around her is indicative of something. I love this.

DWW: And what do you make of the book itself?

JS: I won’t buy the book because in a way, the book is within me already, and we all have our own Selfish. Selfish is a kind of American My Struggle — that’s Karl Ove Knausgaard’s epic, not Hitler’s. I mean, a chorus of one, written in a personal language of compassion, infinite theater, stage sets, setpieces, ceremony, shallowness, despairs, self-awareness, sexuality, unable to curtail one’s selfishness and obsession with one’s own image. Extras enter and leave the stage, but photography, rather than writing, as homeopathic medicament, remedy, used to relieve and express painful malaise. As with Knausgaard, I can imagine Selfish soon being forgotten; another struggle of a young girl inventing herself in and out of the spotlight amidst Southern California insanity, hedonism, and wealth, but at the epicenter of the most highly charged racial trial of an era; where the black man won at the same time as her body became deformed, shaped, changed. All while she does something in public that so many women do it private: look at herself in the mirror and through a camera at the same time. Some kind of love is born and maybe dies in this book, a sort of nervousness, inaccurate explanations, liberation. And I only need to see it once to get all this.

DWW: So why do you suspect it might be so quickly forgotten? Is it because of the medium? Over the last year or two, the selfie’s actually also undergone exactly the kind of category reimagining we’ve been talking about — from punch line and sign of end of culture to subject we can’t stop thinking about as a majorly meaningful relic of the present day. (I really like Ben Davis’s essay “Ways of Seeing Instagram,” in which he argues that all of the major Instagram tropes — self-portraits, luxury-lifestyle brags, pictures of enviable meals — are in fact very familiar tropes from art history.)

JS: We’ll forget because that’s what we seem to do these days. Forgetting is what we did once Obama was elected; we forgot to learn to be disappointed in new ways; instead we reverted to the old, more cynical ways. Things now become more and more of what they already are. In the case of the selfie, it was, briefly, everything; but now it’s just another thing. I would say, however, that the form is going through further permutations, brought on by new tools, technology, selfie sticks, different lenses and filters, etc., so that the form will not die but become so ubiquitous that it will become an invisible genre, like landscape or a rhyme. Something we do because the body likes doing it. Forgetful or not, Kim is a first adapter and partial inventor of a genre. Ravaged nerves of author and viewer notwithstanding. Like I said, an American My Struggle.