La Monte Young has a different relationship to time from the rest of us. His music goes on for a long time — that’s objectively true, and it feels even longer if, like many people, you find it boring. He’s credited as the vastly influential father of minimalism because when he was 22, in 1958, he wrote the first piece that held notes for a long period, suspended in air to allow examination and contemplation. His best-known work, The Well-Tuned Piano, is a solo performance that has grown in length from three and a half hours to five to, last time he played it, nearly six and a half. (It would have been longer, but he rushed a few parts.) When he was young, Young shocked Karlheinz Stockhausen by strolling in two hours late for the intimidating composer’s morning composition class in Darmstadt, Germany. For some time, Young lived on a weekly cycle of five 33.6-hour days. Lately, he stays awake for 24 hours, and then rests for 24.

In a white-carpeted West 22nd Street gallery, the Dia Art Foundation is hosting the Dream House, a music and light installation co-created by Young and his wife, Marian Zazeela. They had five weeks to install it, Young says as he sits in Dia’s vast space, and it will remain there for only four months. Why so short a time? he wonders. What’s the hurry?

Dia acquired the Dream House for a price in “the high six figures,” a source says, which is a lot of money for a piece that’s notional and can’t readily be resold. Foundation staffers were frustrated when Young refused to pose for photos and declined nearly all interview requests. He knows the lack of publicity could hurt ticket sales for his series of performances, which continue through October. But he doesn’t care. “I’m too famous,” he tells me.

Young isn’t interested in temporal popularity; he believes his music will be exalted, because it leads toward enlightenment. “People have written that I’m the most influential composer in the last 50 years, and I think that’s true,” he says. “What’s more, when I die, people will say, ‘He was the most important composer since the beginning of music.’ It’s not just a work of genius — I did things no one ever dreamed of and I set up an approach to sound that parallels universal structure.”

“La Monte isn’t known for his modesty,” chuckles Rhys Chatham, who studied with Young and is best known for writing minimalist guitar assaults. He recalls La Monte saying, “If one invents fire, why should one be modest about it?”

Yet none of his major compositions are in print, he rarely performs, and he places such extensive restrictions on performances of his music that it’s rarely heard. He has all but disappeared, by his own hand. “He’s basically unknown at this point,” says David Harrington, leader of the Kronos Quartet, which commissioned a piece from Young in 1990. “Even young musicians we mentor don’t know about La Monte. It’s tragic.”

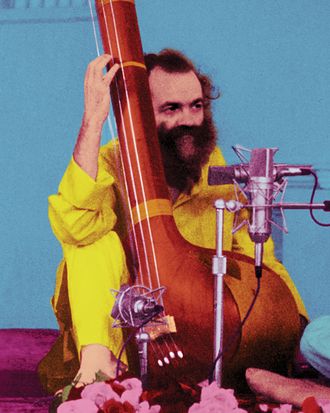

Young’s boasts come off as more charming than annoying. Partly that’s because he’s a tiny 79-year-old who talks like an MIT professor, with a command of math, physics, history, and mysticism, but looks like an elfin Hell’s Angel. Tonight, he’s in his customary uniform: dark jeans, a sleeveless denim jacket, no shirt, and a scarf over his head. He’s hung metal links from his hearing aids. He would look badass-evil if he weren’t mischievous and merry.

Also, Young’s boasts are true. He has, as he claims, “influenced thousands of musicians.” He inspired Terry Riley, who inspired Steve Reich and Philip Glass. He tutored Chatham, a bridge to influencing Glenn Branca and Sonic Youth. John Cale and Angus MacLise played with him in the ’60s, then co-founded the Velvet Underground, which makes Young a source for nearly every alternative-rock band. His experiments with extreme volume and repetition point right at My Bloody Valentine. And Brian Eno, who called Young “the daddy of us all,” spun Young’s long tones into ambient music.

He is the most important living American composer, as he claims. And he’ll remain so even if no one interviews him and no one comes to hear his music. And while Young has made music that defies and distorts time, time hasn’t reciprocated. Young will be 80 in October and he’s increasingly infirm. “When you get to be 80, you start thinking, How am I going to go for another year?” he admits. La Monte Young is running out of time.

He’s worked in New York for 55 years, but Young traces the origins of his music to sounds he heard as a child in Bern, Idaho, especially the high whistle of a hard plains wind running through his family’s log cabin and the sustained buzz generated by electric poles and generators. His father, Dennis, a devout Mormon, worked as a shepherd to pay the $5 monthly rent on the cabin, and was a “brutal” man who beat La Monte and “had no money because he had too many kids and not enough sense to stop having kids. Mormons are like baby factories.”

Although Dennis bought his oldest son a saxophone and taught him how to play it, the family was appalled when he rejected Mormon ideals and began playing jazz in nightclubs. “Mormons were very prejudiced. To be a jazz musician, you have to think black, live black, be black.” One night, a carload of musicians came to the Young house to pick up La Monte for a recording session. His step-grandfather Leonard went to the car and said, “You coons go home.” “I had to get my horn, because my family had hidden it. I ran up the street, got in the car, and I never went back.” Young played with jazz superstars Ornette Coleman, Don Cherry, and Billy Higgins, and beat out Eric Dolphy for a spot in an L.A. dance band.

At the University of California, Berkeley in 1958, while earning a master’s degree and scandalizing the school with his music and appearance (goatee, beret, long hair), Young dated poet Diane Wakoski, with whom he moved to New York before they split up. They were nearly a trio — Wakoski bore a daughter but put her up for adoption. “Diane and I were very poor at the time,” says Young, who’s never before discussed having a child. “Diane didn’t want to give the child away, particularly. But with my background, Mormon baby-makers, I couldn’t take it. I wanted to do music.”

“Within weeks” of Young’s arrival in New York, says the composer and concept artist Henry Flynt, “he’d taken over. All of a sudden, we were all at the end of strings that he’s holding in his hand.” He met and charmed or dazzled everyone worth knowing. He curated a series of concerts at Yoko Ono’s Soho loft (monthly rent: $50.50) that reshaped culture in New York. Flynt recalls giving a performance in Ono’s loft “that largely consisted of pacing the floor.” According to Young, he and Ono had an affair.

“There was an enormous concentration of artists all living in a 20-block radius,” says Chatham. “I can’t begin to say what a sensation that series created. La Monte didn’t need records out to be influential, because anybody who was anybody was going to those concerts. Yoko’s loft was the internet.”

In addition to his hard work, charm, and audacity, Young had another social advantage: He was dealing drugs. Warhol acolyte Billy Name has said Young “was the best drug connection in New York.” “La Monte had hash flown in, concealed in greeting cards,” Flynt explains. His deputy dealer was Cale, who wrote in a memoir that he had moved to New York “to sit at [Young’s] feet.” Young was briefly jailed in 1964; Cale says police had found half an ounce of opium in his loft.

Young invited Cale to join the Theatre of Eternal Music, a group that performed long drones, with only a few notes, at extreme volumes (120 to 130 decibels), creating overtones and phantom notes that ring in the ears even though they don’t exist. Some listeners “fled from the physical pain of the volume after two minutes,” Ron Rosenbaum wrote in the Village Voice in 1970.

They rehearsed every night, for up to six hours. They got high before every concert. “Hashish milkshakes were a feature at one point,” adds trumpeter Jon Hassell, who played with them. “The performances were ecstatic, in a very controlled way.” When Tony Conrad joined on violin, Young allocated him only one note.

The drones they played, inspired by Young’s interest in North Indian music, replaced the 12-note vocabulary of Western music with a set of pitches that have a whole-number mathematical relationship to one another. Proponents of just intonation, as it’s called, believe the 12-note system is chronically out of tune and harmful to our health — as well as the by-product of a conspiracy that involves, depending on whom you ask, the Illuminati, Zionists, the Catholic Church, and the Nazis.

“Are you aware of the 528 movement?” asks Jon Catler, a guitarist who plays with Young. He’s referring to people who believe in the healing power of music in which a C is retuned to 528 hertz. “Supposedly, these frequencies can be used to repair DNA. It’s the frequency of hemoglobin and chlorophyll. It’s kind of a life-giving frequency. This information was known hundreds of years ago, but was buried and secreted. Now there’s a global community waking up to this fact. It can’t be suppressed any longer.”

Anyone accustomed to conventional music will hear just intonation as odd and askew, though its advocates insist the opposite is true. “It’s almost like if you’ve been eating McDonald’s hamburgers all your life, and someone gives you an apple,” says Catler.

Like all geniuses, genuine or self-proclaimed, Young has often been surrounded by acolytes, including some who work for free. “He had a reputation of having many slaves working for him,” Chatham says. Arnold Dreyblatt, a composer who now lives in Germany, became an assistant in the mid-’70s and also uses the word “slave” when recalling that time. “I cherish him as a teacher. He’s an egomaniac, which is fine, because a lot of artists are. And he was always obsessive.” Dreyblatt recalls getting a lesson in proper vacuum cleaning from Young, who treated it as seriously as a composition class. “It was insane. But even in the worst of times, he had a charm that kept you in.”

Their guru was part of the package, too. Young and Zazeela became disciples of Pandit Pran Nath, a master of kirana singing, a Hindustani style that involves tiny gradations of pitch; they studied with him for 26 years, and he lived in their Tribeca loft until he died in 1996. “We were happy to take care of him night and day,” Young says. One of Young’s former assistants, who requested anonymity, was less happy about it. “Pandit Pran Nath started sending me out for beer, and he was drunk all the time. He was running after me, and drunk.”

The daughter Young and Wakoski placed for adoption, whose name is Leann, tracked down her birth parents years later. (Young offered to teach her music, but she declined.) She’s a bookkeeper, living in a town near Sacramento, and her online profile lists Christina Aguilera and Keith Urban among her favorite musicians, which makes a good case for the effect of nurture over nature. Young and Zazeela, married since 1963, never had children. Kids are too rebellious, he says. “A disciple is what you want.”

And what they got. For years, Young insisted on being interviewed in tandem with Zazeela, who has the earthy directness of a native New Yorker. Now they are always joined by Jung Hee Choi, co-creator of the current Dream House, which uses her light-based sculpture and sine-wave drones. At times, she’s an equal, and at times, she isn’t; Young dominates the conversation, sometimes cuing her by saying, “You talk,” and Choi prompts him with forgotten details.

A 45-year-old born in Seoul, Choi fled Korea’s restrictive social norms and a father she calls “authoritative.” (Arnold Dreyblatt uses the same word to describe Young.) When people asked why she came to the U.S., she says, “My metaphorical answer was, ‘I come here to smoke pot.’ Not literally.”

Her discipleship requires extreme subordination. One day, Choi forgot to touch Young’s feet, a sign of respect in Indian culture. “I threw my bag at her,” Young says. “I think she was totally shocked.” Yet her masters’ frailties make her essential: “Initially, everything depended on us. Gradually, we’re falling apart, and everything now is depending on her,” he says.

So Choi is more than a disciple. “I am their mind-born child, and they’re supposed to leave their souls to me when they leave this Earth.”

“We will leave our souls to her. She will inherit our kingdom,” Young says, which means, among other things, Choi will decide what music to release from his invaluable private archive of recordings. “We’ll die, and she’ll carry on. I can’t see putting it any other way.”

Young’s grand ideas require big budgets, which they find in commissions and grants. “I get paid a lot of money,” he told me in 2000. “You add zeros when you get me instead of the other composer.”

For years, he had an indulgent patron in Dia, which spent $4 million to convert the old Mercantile Exchange building into a customized palace. He and Zazeela moved there in 1979; Dia gave them 22 assistants and a yearly budget of $500,000, which allowed Young to install a dedicated “beard sink,” where he could wash his whiskers. But the Dia founders were more generous than prudent, and after they were deposed, the building was sold in 1985.

Ever since, Young and Zazeela have scrambled for money. She was bedridden for two years with an immune-system disorder, and he has been slowed by osteoarthritis and prostate surgery. “We don’t have a penny saved,” she says. According to tax documents, their Mela Foundation had income of almost $1 million over the past three fiscal years, but their expenses nearly matched that, and they have assets of only about $60,000. You can’t expect practicality from a man who plays piano for six and a half hours.

When he wrote Trio for Strings, Young was poor, living on mustard sandwiches. (“I bought the bread and stole the mustard,” he said.) Once he finished the exposition section, he realized the piece was already an hour long, and when completed, would take two to three hours. “So I made the first and last compromise of my life — I shortened it.”

On September 3, Young will finally present the uncompromised version of Trio for Strings at Dia. He considers it to be a world premiere. It took only 57 years to get it right.

*This article appears in the June 29, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.