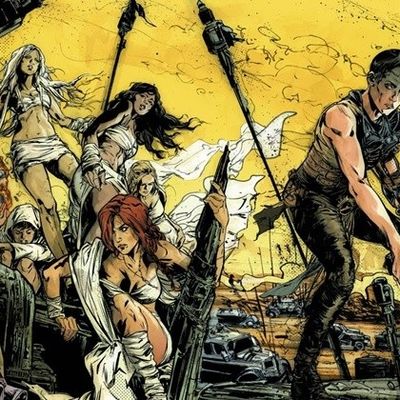

Let’s be clear: The first Mad Max: Fury Road tie-in comic, Furiosa, is not good. It is, in fact, very bad. If I had a physical copy instead of a digital one, I would take great joy in ripping it into small pieces and throwing it away. I’m not alone in this; it’s been fisked in great detail, blamed for ruining the movie, and eventually tossed out and rewritten wholesale. The problem, in brief: Furiosa takes the movie’s complex, human, vibrant female characters and flattens them down to a few drab, crummy tropes, notably by fixating on the wives’ (and, it is revealed, Furiosa’s) rape and mistreatment at the hands of Immortan Joe.

But the problem with the Furiosa comic isn’t that it’s exceptionally anti-woman. It’s that it’s so, so very NON-exceptionally anti-woman. I have read comics that go out of their way to craft a rape scene that will be maximally stomach-churning and grotesque (Neonomicon, I’m looking at you, and then I’m looking away very quickly). This definitely isn’t that. The writers and artists aren’t seeking to degrade their characters; they simply don’t want to put forth the effort to give them dimension or nuanced motivations or realistic speech. I understand and respect the horror of commentators who found Furiosa revolting, but personally, I had a hard time getting riled up. It’s just so hackish. So trite. So lazy.

And that, right there, is the problem. A lazy piece of comics writing about a woman only has a few well-worn channels it’s likely to flow into: She’s not like the other girls because she’s more like a man! She’s damaged by her own rape! She’s trying to avenge the rape of others! She’s doing it all out of love, for a man or her children! Furiosa uses most of these. But a lazy piece of comics writing about a man — well, there are just so many more plotlines you can trip and fall into: Man has a source of too much power and must destroy it before it destroys him! Man defends righteousness in court despite being the underdog! Man kills father and marries mom! It’s not an accident that the traditional four types of dramatic conflict — man versus man, man versus nature, man versus society, man versus self — all have one word in common.

Take Mad Max: Fury Road: Max Part One, which came out last week. It’s okay! It’s no more artful than Furiosa, and no more novel — in fact, not only is it a story we’ve seen before, but it’s a story we’ve seen before within the Mad Max universe. Gastown is letting everyone in for the night, even scavengers like Max, and they can all compete in a giant brawl to the death. Man versus lots of men, if you will. (GUESS WHO WINS.) It’s literally Thunderdome — like, the action actually takes place in a Thunderdome — but a melee rather than a duel.

There’s nothing fundamentally bad about this plotline, bare-bones and brutal though it is. If you don’t believe me, go read the Achewood story “The Great Outdoor Fight,” which takes the massive death brawl concept to a lofty, strange, hilarious, and sometimes tender place. (If you do believe me, go read it anyway.) But it’s not exactly unbroken ground. There’s “The Great Outdoor Fight,” of course. There’s Battle Royale. There’s thousands of Lobos fighting each other to the death. There’s Community’s “Paintball Assassin” death match, itself a nod to the trope’s pedigree. There’s, uh, Beyond Thunderdome. And this long heritage, this fundamental familiarity, means that a writer can half-ass this plotline and be assured it will still more or less do the trick.

(The Hunger Games does “massive fight to the death” with a female protagonist, of course — but whatever you think of The Hunger Games, it’s miles from being lazy. One of the first indicators: It does “massive fight to the death” with a female protagonist.)

Writer Mark Sexton, judging from the Furiosa comic, desperately wants to half-ass it. Or maybe he doesn’t and George Miller and Fury Road scriptwriter Nico Lathouris strong-armed him into it, exhausted by the sheer mental effort of writing something that treated female characters like humans and needing somewhere to store their extra rape plots. Doesn’t matter. The point is that Sexton, who co-wrote Furiosa and wrote Max Part One on his own, chose a plot for Max he could phone in if he wanted to, and it came out fine; with a male lead, you can be lazy without getting gross. There are more of those plots to draw on, and they’ve have had longer to build up, to become hackneyed enough that they’re easily available even to a writer who’s not trying.

Lazy writers, when doing stories that feature women, are drawn magnetically to woman-denigrating plotlines because those are the ones so baked into the culture that they become easy. The Furiosa writers probably didn’t make the title character a brooding sexual-assault survivor because they wanted to take her down a peg; they did it because they couldn’t be bothered to do something more interesting. That is, of course, an extra disappointment because it runs so counter to the spirit of the movie. And it’s especially frustrating because it’s not a matter of bad storytelling, but a matter of a culture that condones and incentivizes bad stories.

“Women are harder to write,” a friend protested when I told her Furiosa was a shambles. That may be true — but if so, it’s because there are so few models. Women characters are “harder” because they offer fewer paths for the lazy writer; they feel harder because women-driven stories haven’t had a chance to rise to the pantheon of cliché.

We need more good writing about women, yes, especially in comics. But maybe even more than that, we need more bad writing about women. We need a full spectrum of ways for women’s stories to be trite, hackish, done to death — or rather, we need it to seem unremarkable when trite stories have women in the lead. Only then will we get a Furiosa comic that feels more like Max Part One: obvious, unoriginal, perfectly fun and fine, with characters who don’t need to be demeaned or dehumanized just because no one can think of a better idea.