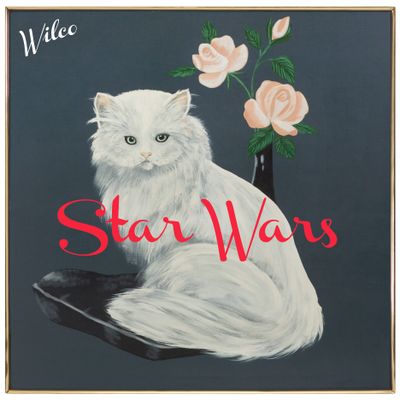

On Friday, Wilco surprise-released, for free on their website, a new album called Star Wars. Variations on this type of release strategy are so in vogue right now that they’re becoming the new normal, but it’s worth pointing out that Wilco are pioneers on this particular front. Chicago’s favorite sons have been pulling this sort of thing since 2001, the year they made a strange, relatively challenging, and stupendously beautiful record called Yankee Hotel Foxtrot. When they played the finished product for their label, Reprise Records, the suits didn’t hear a conventional single, and dropped Wilco. (The whole story is chronicled in Sam Jones’s gorgeous black-and-white documentary about the band, I Am Trying to Break Your Heart — highly recommended if you haven’t seen it.) In September of that year, having retained the rights to the masters but still stuck in between-label-deal limbo, Wilco took matters into their own hands and posted Yankee Hotel Foxtrot to stream for free on their website. A line from Greg Kot’s Wilco book, Learning How to Die, shows how far the band, and the internet itself, has come: “On the first day, the band’s Web site logged fifteen thousand visits, more than eight times the normal traffic.”

Though we hardly blink at this sort of thing now, it was a risky and controversial move 15 years ago — remember, these were still the days when Lars Ulrich was blowing his top over Napster. People feared that this kind of digital magnanimity would hurt Wilco’s bottom line. They turned out to be very, very wrong. Even with those free streams, Yankee Hotel Foxtrot sold better than any Wilco album before (it’s still their most commercially successful album) and it elevated them to a new level of critical acclaim. The story of the record turned into an optimistic parable about music distribution on the internet — how the cream rises to the top, and how bands are cosmically rewarded for changing with the times. As the decade went on, it also became a great metaphor for the obliviousness of major labels. Reprise’s rejection of the supposedly inaccessible YHF is all the more laughable today; a “single” from the album, “Jesus Etc.,” is the band’s all-time most played song on Spotify.

Almost 15 years later, as the industry crumbles around them, Wilco are still standing steady and tall, having eked out the kind of secure position in the rock landscape that would have those dudes at Reprise salivating. They somehow became household names on their own terms. They have their own music festival. They make cameos on prime-time sitcoms. But over the past decade, as they’ve become even more well-known, the band’s creative ambitions have stagnated a bit. They followed up their glacial, masterly 2004 record A Ghost Is Born with, by my measure, their worst album, the tepid, sandpapered Sky Blue Sky, and the only-slightly-better Wilco (The Album). Their most recent record, 2011’s The Whole Love, was slightly more sonically adventurous, but it felt uneven and not particularly memorable. In their advancing age (this year marks Wilco’s 21st birthday), the once-restless band seemed to be settling for comfort.

Star Wars proves this arc wrong. It’s an itchy record, shaking off complacency at almost every turn (the tone is set by a squalling, atonal opener called “EKG”). Pound for pound, it’s my favorite Wilco album in a decade. It’s also the shortest Wilco album ever and — maybe because of this — something about it feels unassuming, even in its boldest and most outré moments. My main qualm with the direction that the band took around the time of Sky Blue Sky was that they started to sound a little too … well … sunny. That’s not the kind of weather native to Jeff Tweedy’s imagination. There’s a great tension in his best music that comes from listening to an introverted, sweet-but-sorta-curmudgeonly guy try and make peace with the world around him. (I’ve always thought that Yankee Hotel Foxtrot sounds like the world’s most mellifluous headache.) Tweedy’s at his most intriguing when he’s a little grumpy and rumpled; after all, the signature moment of every Wilco concert comes during Being There’s folk-rock epic-poem “Misunderstood,” when he screams until he’s hoarse, “I’d like to thank you all for nothing … nothing … nothing … nothing at all.” Like vintage Wilco, Star Wars is prickly in all the right places. “Now you want more than we have / More than there is,” Tweedy chides on the knotty, static-charged “More,” as distortion curdles around him. In turn, and unlike on Sky Blue Sky, the moments of softness and sunshine (a sighing backing vocal, a sticky chorus melody) feel wrestled-for, negotiated, earned.

Wilco’s second act began when the avant-jazz guitarist Nels Cline joined the band for its tour in support of 2004’s A Ghost Is Born.* But in subsequent years he’s struggled to integrate into their existing sound, sometimes feeling more like a mutant appendage than a natural outgrowth of the band’s frame. But Star Wars makes space for him rather generously; the record is alive with intriguing, often bristly guitar textures that provide a nice foil for Tweedy’s warm-milk mumbles. Cline brings an unvarnished finish to rockers like “The Joke Explained” and “Pickled Ginger,” but he really shines on “You Satellite,” the record’s answer to Wilco 2.0 fan-favorites “Spiders (Kidsmoke)” and “Black Bull Nova.” Though it’s a strange thing to say about a band that started out in the gap between power-pop and alt-country, these kind of spacey, droning kraut-rock freak-outs are what Wilco have come to do best in their advancing age. When “You Satellite” locks into a groove, it’s gloriously hypnotic — I actually wish it were longer. Same goes for “Where Do I Begin,” which begins as a jangly, Tom Petty–esque guitar-and-voice ditty before exploding into a Cline-driven passage of signal-flare guitars — the perfect yang to Tweedy’s soft, undemanding yin. The song feels unfairly short; I could have listened to Cline paint the sky like that for at least another five minutes.

Structurally, “Where Do I Begin” is a throwback to Yankee Hotel Foxtrot’s “Radio Cure” and “Poor Places” — trembling folk songs that eventually burst and expose their twinkling, cosmic innards. And while nothing on Star Wars (except for maybe the sweetly lyrical closer “Magnetized”) has the emotional immediacy of those earlier songs, the record still bottles just enough of their spirit to earn its name. A halfway point between their days of antsy innovation and their more recent years snoozing in the comfort zone, Star Wars finds Wilco stumbling upon a quietly adventurous sound.

*A change was made to reflect the fact that Nels Cline did not join Wilco until after the recording of A Ghost is Born.