In so many ways, Dr. Dre’s new album, Compton: A Soundtrack, is a pleasant surprise. First, there is the fact that it exists at all. Before last week, the phrase “the forthcoming Dr. Dre album” was a punch line in and of itself, thanks to the good doctor’s mythically delayed, over-ten-years-in-the-making third album, which, since 2001, was set to be called Detox. As the years went by, the expectations became more impossible and the hype more biblical (in 2004, Dre’s onetime co-producer Scott Storch called it “the most advanced rap album musically and lyrically we’ll probably ever have a chance to listen to”), so it was something of a relief when Dre finally announced on Beats 1 last week that he’d scrapped Detox for the supremely humanizing reason that “it just wasn’t good.”

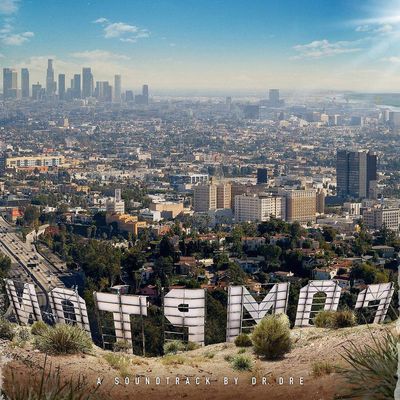

But, in the same breath, he confirmed that he had a new record on the way that he was actually proud of: Compton: A Soundtrack. He wasn’t kidding. A bigger surprise than the simple fact of its (very rapid) release is just how self-evidently good this record is. And how urgent, and how vital, and how audaciously, expensively weird. Compton is an ornately cinematic, meticulously realized ode to the embattled home Dre’s been repping since his days with N.W.A — the curtain opens on an ironically stuffy news broadcast: “Compton was the American Dream, sunny California with a palm tree in the front yard, the camper, the boat” — dotted with moments of technical daring and scene-stealing cameos. It has, at its core, a fire that feels unexpected given Dre’s current level of material comfort. It’s not every day that you hear someone so successful still sound so genuinely hungry. As far as savvily timed, corporate-tie-in-slash-comeback-albums go, the vividly panoramic Compton makes Jay Z’s Magna Carta Holy Grail look like a stick-figure drawing.

And it’s evident from its opening notes, beginning with a breathtaking moment when the monster-truck beat drops on “Talk About It”: This shit bangs. Hard. The first two voices we hear aren’t Dre but the boisterous, 25-year-old up-and-coming rapper King Mez (Dre has enough faith in him to feature him on the album three times, the kind of co-sign rising rappers’ dreams are made of), followed by the little-known Dallas rapper/crooner Justus. Both hold their own. Dre has always been a reliable cultivator of new talent, and it’s easy to assume that Detox’s endless delays had something to do with him prioritizing other people’s records over his own. True to form, Compton has enough guests to fill an Apple conference room: Kendrick Lamar, Eminem, Ice Cube, Xzibit, Jill Scott, Snoop Dogg, the Game, Marsha Ambrosius, Anderson .Paak … I could go on. Still, this ensemble is curated carefully enough to actually mean something — thinking about who’s not on this album is just as fascinating as who is.

Even though Dre doesn’t name names specifically, this is a record lobbing Molotov cocktails at hip-hop’s status quo: “Yeah, I mean, I listen to these rap records, half the time I’m suspicious,” he begins on the woozy and barbed “Satisfiction”; a few lines later, Snoop drops in, delivering his lines with hilariously exaggerated disgust, as though he’s just smelled something foul in the room: “These labels always ask me to do a song with these niggas / Doc, I think it’s time for you to open up the pharmacy, nigga / And change this fuckin’ music shit, my nigga, you should consider.” Compton isn’t a record interested in glad-handing rap’s current reigning class or vampirically latching onto its proven hit-makers. It’s instead a steely, braggadocious sneer from an elder: Is that the best you can do?

More than any other guest, Kendrick looms largest over Compton — and not just because he has all the best verses. In ambition, scope, and tone, Compton feels like a conscious companion piece to Lamar’s knotty epic To Pimp a Butterfly. Both records share a cinematic (and borderline operatic) quality, a nostalgia for the ghosts of West Coast rap past, and a sustained intensity that, as a listener, can sometimes feel downright depleting. Kendrick lends a sense of manic gravitas to three of the album’s darkest tracks: He’s thrillingly agnostic on “Genocide” (“Fuck your blessing, fuck your life, fuck your hope, fuck your mama, fuck your daddy, fuck your dead homie”), uncharacteristically casual on “Darkside/Gone,” and, it seems, coming for Drake on the impressionistic “Deep Water” (“Motherfucker know I started from the bottom”). Dre aligning himself so vocally with Kendrick is telling; Dre allowing Kendrick space on his album to take shots at Drake even more so. It’s Dre’s subtle way of co-signing substance over style, which right now feels like a traditionalist approach. (At one point, he reminisces about a time “when a rapper needed guns way more than a stylist.”) The tortured-artist tendencies of Compton prove Kendrick and Dre to be kindred spirits — both wear their crowns heavily.

The Chronic was, prototypically, a weed record; Compton is a ‘roid record. In stature and in flow, Dre’s hardened with age — the guy who gave us hip-hop’s very first blockbuster beach album this time around isn’t touching “carefree” with a ten-foot pole. (A first for a Dr. Dre record, Compton feels defiantly anti-single.) At points, I like how restless he sounds. The great, revealing “All in a Day’s Work” (“Some of my friends don’t understand, shit, I gotta work / Always talkin’ ‘bout bustin’ the club but I’m like, ‘Fuck that, I gotta work’”) paints a very honest portrait of Dre the technician and perfectionist; you very much get the sense that this is the kind of guy who could easily get too in his own head to finish a decade-long project. But elsewhere, the atmosphere of Compton can feel a little too puffed up and self-serious for its own good. Here it seems to be inspired by To Pimp a Butterfly’s worst tendencies, namely its humorlessness and high drama. (Compton needs a little less “u” and a little more “i.”) Even Snoop — the guy you used to call for a little comic relief — sounds like he’s inhaled some of the protein powder in the air. He comes on “One Shot One Kill” like a bulked-up Marvel villain. Remember when rap skits were funny and dopey, rather than audition monologues for Oscar-baiting dramas? I never thought I’d be waxing nostalgic about all the “deez nuts” jokes on The Chronic, but … here I am.

Nostalgic as it is, though, none of the veterans embarrass themselves too badly. There are corny moments, but they’re the kind that make you smile rather than cringe. (I cannot resist a chuckle every time I hear Cube say, “Cashed a lot of checks this morning / Yesterday was a good day.”) Unfortunately, though, Compton finds other ways to feel old-fashioned. One of its most ill-advised moments comes at the end of the brooding “Loose Cannons,” in an overwrought, way-too-Kendrick-inspired skit in which a man shoots and kills his girlfriend (but not before we get to hear her pleading for her life for about 30 seconds), and then calls up some friends to bury her. (“Man, this bitch is heavy!” “Nah, you gotta get under her armpits.”) Could this be a symbolic tableau meant to interrogate the historical sacrifices and erasures of black women for the greater good of the black man? Nahhh, it’s just some lazy, garden-variety misogyny. Or maybe it’s beyond garden-variety, because there is something extraordinarily grotesque and astonishingly unself-aware about a man with a public reputation for beating women making the listener sit through some weak-ass radio play in which a woman suffers audibly and then meets a violent, excruciatingly detailed death. We’re really still doing this Slim Shady shit in 2015?

Well … cue the inevitable Eminem verse. When Slim storms the scene in the penultimate track, “Medicine Man,” it is — structurally, technically — a spectacular moment. Like almost every Eminem verse, it’s technically breathtaking; like almost every Eminem verse, it contains some stupid shit that completely takes you out of the spell. “I even make the bitches I rape come,” Eminem brags, the line unwittingly emphasized because rape is the only word on the album that is bleeped — giving the moment this very desperate air of, “Aren’t I shocking?” The only thing shocking is that Em hasn’t realized how embarrassing this stuff is by now. His lines about raping and murdering women have aged about as well as the ones about Carson Daly and Fred Durst, and yet he persists. “N****s be 44, actin’ half they ages,” Dre chides earlier in the song, as though he and everyone he’s selected to be on his album are paragons of maturity. Ironically, their tone-deaf, blasé, and utterly outdated glorification of violence against women makes him and Em seem about twice as old as they actually are.

But, blessedly, Compton demonstrates good taste in other ways. This record could have succumbed to so many pitfalls. It could have gone the maudlin, radio-pandering route of Dre’s last single, the Skylar Grey collabo “I Need a Doctor.” It could have (as I deeply feared it would when I heard its title) featured cheesy sound bites from Straight Outta Compton, the forthcoming N.W.A biopic that reportedly inspired it. It could have felt like a marketing strategy rather than a great rap album but, miraculously, it does not. Instead, it’s a sharp, immaculate-sounding record that earns its status as the finale to the solo career of rap’s great tinkerer. I like it a lot. But loving it is complicated.