Samuel L. Jackson remembers the exact moment he met Quentin Tarantino, because, well, it’s hard to forget the motherfucker who screwed up your audition for Reservoir Dogs. That was 24 years ago, and Jackson still calls Tarantino a motherfucker, though now “it’s the endearing motherfucker, not the curse motherfucker,” he says, as in their common greeting, “What the fuck, motherfucker!”

Jackson tells the tale of their first encounter with the kind of affectionate shit-talking born of deep friendship; they’ve just finished their sixth movie together (The Hateful Eight, out December 25). It was 1991, the year Jackson, a theater veteran just getting into movies, won Best Supporting Actor at Cannes for Jungle Fever. He’d shown up to casting for this unknown screenwriter’s first feature having memorized a scene he thought he’d be playing with Tim Roth and Harvey Keitel. Instead, he got stuck reading with two bozos he’d never seen before, who didn’t know their lines and couldn’t stop laughing. “I didn’t realize it was Quentin, the director-writer, and Lawrence Bender, the producer,” says Jackson, “but I knew that the audition was not very good.” He didn’t get the job. “My agent and manager tell me that my expectations of everybody else being as prepared as I am is my biggest problem,” Jackson tells me.

It wasn’t until Reservoir Dogs’ notorious premiere at the Sundance Film Festival the following January that Jackson saw Tarantino again. Half the audience had fled amid all that gleeful gore; Jackson went up afterward to shake Tarantino’s hand. “He’s like, ‘Yeah, yeah, yeah, I remember you. How’d you like the guy who got your part?’ ” says Jackson. “I was like, ‘Really? I think you would have had a better movie with me in it.’ ” (Let it be known that Jackson’s well-honed Tarantino impression sounds like an unholy amalgam of Gollum, Joe Pesci in GoodFellas, and the Looney Tunes Road Runner.)

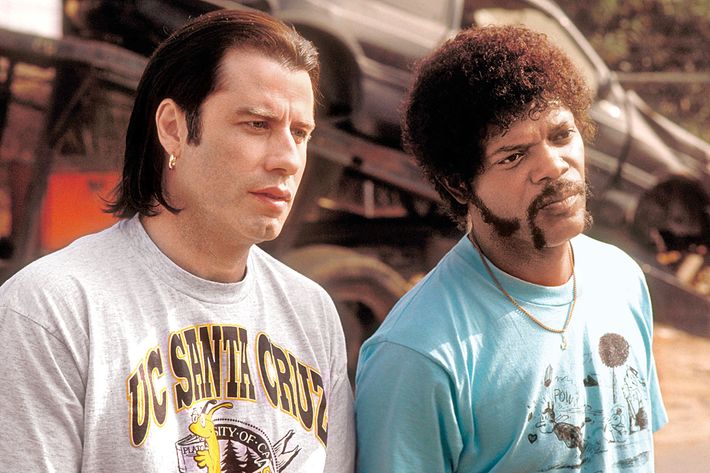

Tarantino told him not to worry; he was writing something for him. Two weeks later, a brown paper package arrived. The images of two gangsters were printed on the front, and a note inside read, “If you show this script to anyone, we’ll show up at your door next week and kill you.” It was Pulp Fiction, whose Bible-quoting hit man “in a transitional period,” Jules Winnfield, would make Jackson a household name at age 46. But only after someone in casting greeted Jackson as “Mr. Fishburne,” and he got so pissed off he murdered his audition.

Tarantino has said that Jackson, along with Christoph Waltz, is “one of the greatest actors to ever say my dialogue.” If most actors come into Tarantino’s world with an 80 percent understanding of how to deliver what he wants, says The Hateful Eight’s Walton Goggins, “I think with Sam, it’s almost 94 percent there.” Since Pulp Fiction, Jackson has appeared in nearly every movie Tarantino has made — an honor not even Waltz or Uma Thurman can claim: the arms dealer Ordell in Jackie Brown; the piano player who gets blown up minutes into Kill Bill: Vol. 2; the narrator for Inglourious Basterds (“Quentin didn’t believe I could learn enough French to be the other black guy — I would’ve figured it out!”); and what may be the meatiest role of his 120-plus-movie career, a former Union officer turned bounty hunter in the lawless aftermath of the Civil War in The Hateful Eight. Jackson embodies the swagger and defiance that course through Tarantino’s revisionist realities — such as, this time, a black man being the central character of a classic Western. He and Tarantino are the cinematic equivalent of an old married couple, with a near-perfect collaborative streak — “except Reservoir Dogs,” Jackson can’t help but point out. Again.

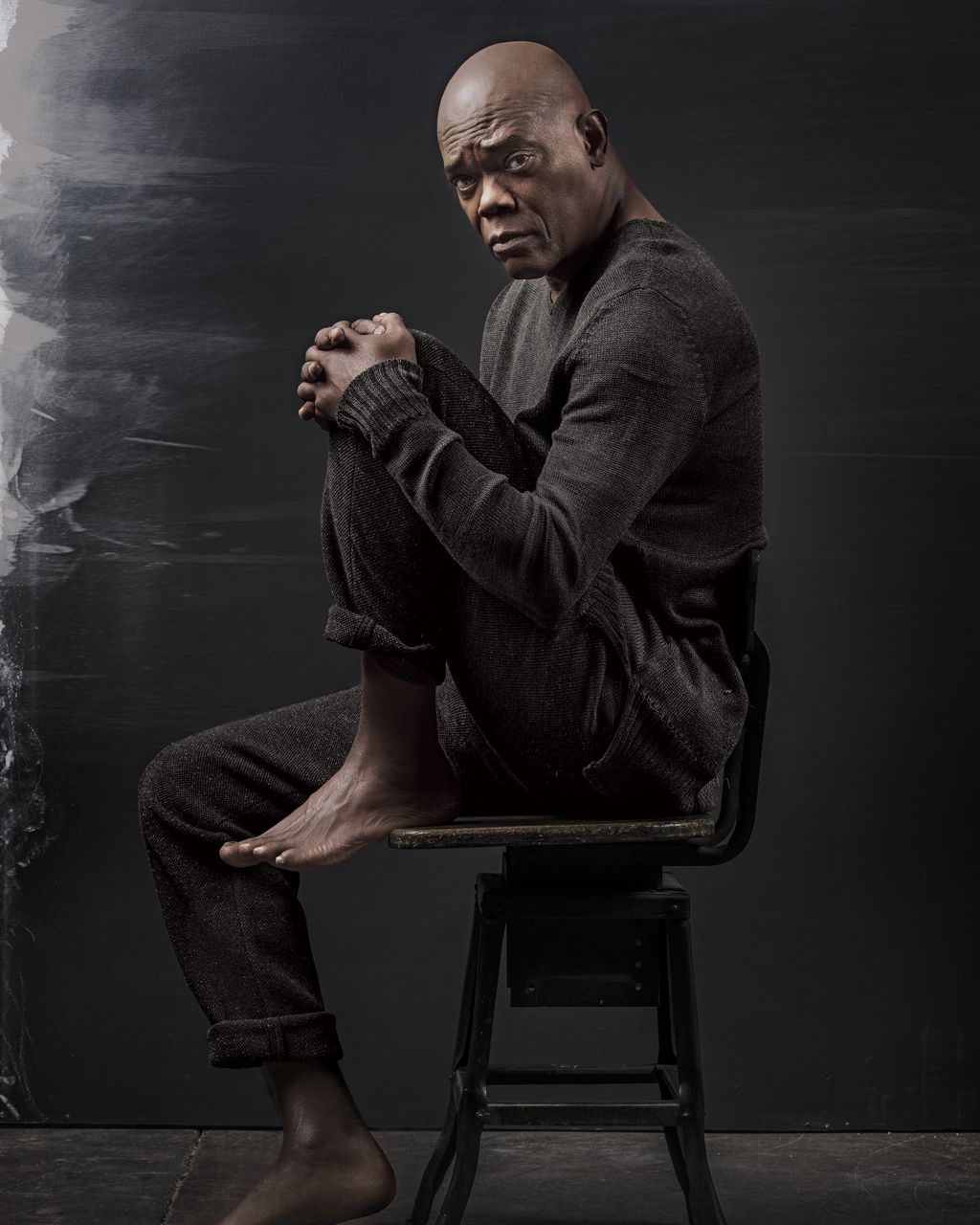

At 66, Jackson radiates a self-assurance and contentment that ought to be bottled and sold at John Travolta’s Scientology meetings. We’re talking at a photo shoot in Los Angeles, to which he’s just returned after a three-week vacation cruising the Amalfi Coast and Côte d’Azur on Magic Johnson’s yacht. They live across the street from each other in Beverly Hills, go to the same church, and do this trip every year with their wives. Jackson always travels with 30 to 40 movies, usually old-school and emerging Asian cinema, which he watches with the guys while, he says, “the ladies watch whatever series that they didn’t binge-watch all year.”

Lunch arrives, and Jackson joins the photo crew, chowing on a lamb burger out of a takeout box. He tried veganism but abandoned it recently after “somebody threatened to fire me from a job if I didn’t gain 20 pounds,” he says. Group conversation lands on Japanese tidying expert Marie Kondo, and Jackson’s manager explains to him Kondo’s philosophy of picking up every object in his house, asking if it brings him joy, and, if not, thanking it for its service and discarding it. Jackson does a double take. “Do you know how long that would take me?” he says. “A long fucking time!”

The shoot’s stylist interrupts us to tell Jackson he can have that gray cashmere sweater he liked for the low, low price of $375. He gives her all the cash he has, and his assistant goes to the ATM to get the rest. “Something else I have to apologize to, to get out of my house,” Jackson says and pretends to talk to the sweater, Kondo style. “I’m sorry I brought you here. I know I only wore you once, but they took my picture in it. I have to let you go.”

This year alone, Jackson has shot The Hateful Eight; reshoots for Tarzan; Tim Burton’s Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children; and Spike Lee’s Chiraq, a hip-hop retelling of Lysistrata. It’s only their second movie together since Jungle Fever; they had a public falling-out when Lee criticized Tarantino’s use of the N-word in Jackie Brown, and Jackson took Tarantino’s side.

Jackson even squeezed in time for some Capital One commercials. “They’re hilarious. I used to watch Alec Baldwin and Jimmy Fallon do them and think, How would I say that? ‘What’s in your wallet? What’s in your wallet?’ So when they called, it was kind of like, ‘Really? For real? Okay!’ ”

The man has done so many movies — including three Star Wars prequels and his nine-picture deal with Marvel as superspy Nick Fury — that Guinness World Records lists him as the highest-grossing actor of all time. When I intimate that he doesn’t have to worry about money anymore, he scoffs. Those grosses belong to studios and producers. “Everybody worries about money, except for billionaire people,” he says. “There’s no b in my money.”

Yet all that activity somehow feels like biding time between Tarantino movies. “Quentin and I have a kind of cinematic affinity,” says Jackson. They discovered it on the set of Pulp Fiction when Jackson was doing his usual binge of Asian movies. “Quentin would walk by my trailer, and he would always hear the sounds of either kung-fu fighting or bullets going off, and he would look in the door and say, ‘What are you watching?’ ” says Jackson. They also realized they’d both spent much of their comic-book-obsessed childhoods in Tennessee in the care of their grandparents, and to this day they do regular movie nights at Tarantino’s house, because, says Jackson, “he’s got a bigger theater.”

“It feels, to me, that Quentin’s leading man is Sam,” says Tim Roth, an original Reservoir Dog and a member of the Hateful Eight. “And I think that’s an extraordinary circumstance, for a white man, however talented, to be able to write for a leading man, a black actor, and give him such a range of roles.”

Take, for instance, 2012’s Django Unchained, in which Jackson plays Stephen, an elderly house slave who’s risen to power by torturing his fellow slaves — or, as Jackson calls him, “the most despicable negro in cinematic history.” Jackson says some of the stuff he did as Stephen was so twisted Tarantino didn’t include it in the final cut. “He was like, ‘People hate you enough. I don’t know if I want people trying to kill you on the street.’ ”

The Hateful Eight, set seven or eight years after the Civil War, is in many ways a Django sequel. Jackson plays Major Marquis Warren, an ex-slave and veteran of the Union Army. He’s also the smartest guy in several very small rooms — a stagecoach and then a trailside watering hole, where Warren and his travel companions of questionable trustworthiness escape a blizzard and find themselves trapped with more untrustworthy outlaws who act as though the war isn’t over. The movie has changed since a copy of the script leaked, but its essence as both a shoot-’em-up and a whodunit remains. Tarantino and Jackson have taken to calling Marquis “Hercule Negro, like Hercule Poirot,” says Jackson, “because he is a bit of a detective.”

The cast, a collection of Tarantino all-stars — in addition to Roth and Goggins, there’s Michael Madsen and Kurt Russell — spent nearly six months in close quarters, much of it on an L.A. soundstage set to 34 degrees to mimic blizzard conditions. They’d sit in a circle drinking coffee, smoking, and telling stories “in various states of disarray and blood, waiting to go back into the fridge,” says Roth. Jackson gave everyone a vintage-style Colt 45 with the movie’s title engraved on the handle as a wrap gift. The cast is still so attached they have a months-long group text chain called the Hater Board where they all check in with one another two to three times a day. Jackson’s wrap text to them: “Go out hard, motherfuckers!”

As usual, Jackson is bracing himself for the barrage of complaints from people who say Tarantino uses the N-word too much, or that as a white filmmaker, he doesn’t have the right to use it at all. He recalls how Django was rendered an “entertainment popcorn movie” as soon as 12 Years a Slave came out, even though he thinks Django was far more disturbing. “Unfair comparisons were made between the two films, and it was more about Quentin using the word nigger 102 times in the movie,” says Jackson, “and it’s like, well, there’s one song in 12 Years a Slave where they say nigger like 300 times! But it’s a song, so it’s art?”

The actor makes a credible Tarantino defender: He was suspended from Morehouse College in 1969 for barricading the board of trustees in a building (“We had to let Martin Luther King’s dad go. He was complaining of chest pains, and we didn’t want to get charged with murder”). Jackson served as an usher at MLK Jr.’s funeral and was a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. When anyone from Spike Lee to young black filmmakers criticizes Tarantino’s choice of words, Jackson says, “I tell them, ‘He’s telling his story. If you’ve got a problem with that, then you need to write your story.’ We’re talking about people living in a specific time who speak a specific way, who still do speak a specific way in parts of the country. I grew up in the South in segregation. I heard it every day. And people who didn’t say nigger said niggra, which was like, Why don’t you just go ahead and say it? It sounds the same to me.”

Though it was written in 2013, the movie’s exploration of how the Civil War didn’t end racism is unexpectedly relevant now. Jackson, for one, thinks that taking down the Confederate flag is an ineffectual gesture. “People still got it on their license plates. It’s just part of the fabric of the South,” he says. “I don’t mind knowing who the enemy is if they want to announce it.”

The afternoon is waning, and Jackson wants to use the remaining hours to fix his golf swing. Then he’s headed to New York to catch the opening night of Hamilton, followed by the premiere of Show Me a Hero, David Simon’s new HBO show, starring his wife of four decades, LaTanya. He’s also planning on catching Straight Outta Compton in the theaters. Jackson likes to sit with a real audience for most movies, especially his own. He claims to have seen 2014’s Kingsman: The Secret Service, in which he played a billionaire ecoterrorist, eight or nine times. “I’m 66! I can show my ID at the theater and get a discount. And I do!” he says, clapping his hands together loudly. “I’m not too proud. I’ve earned it.”

*This article appears in the August 24, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.