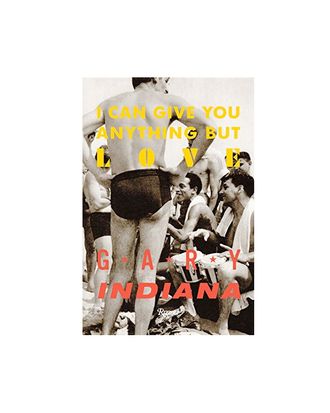

Writers have a hard time controlling what they’re known for: It could be the wrong book, or no book at all but instead some provocation, feud, love affair, scandal, or autopsy. In his new memoir, I Can Give You Anything But Love, Gary Indiana laments that a young reporter profiling him seems mostly interested in “the art criticism I wrote for three years in the mid-1980s … a bunch of yellowing newspaper columns I never republished and haven’t cared about for a second since writing them a quarter century ago.” A memoir, of course, is an opportunity to shift the emphasis. But it’s no surprise that a crucial player in the East Village art scene of the ‘80s — an era that’s attracted acute nostalgia as one of the last gasps of downtown authenticity, and a phase when there were still giants in the pages of the Voice — would be identified with that time. The cultural appetite for a bygone Manhattan is evident in the laurels and big advances for touristic historical novels like Rachel Kushner’s The Flamethrowers and Garth Risk Hallberg’s City on Fire.

Indiana, by contrast, is the real thing. But nostalgia isn’t part of his equation. He’s the author of seven novels, and a prolific essayist and critic; he’s been a playwright, stage director, and film actor, and has been exhibiting his visual art for a decade or so. You don’t need a complete knowledge of his works to see that his novels mark him as the nearest thing we have to an inheritor to the Burroughs strain in American fiction. That’s the strain that breaks or simply ignores middle-class taboos; embraces narcotics and all kinds of sex; takes an interest in the uglier emotions, like disgust, shame, and hatred; applies actual pressure to American myths (the Western, the P.I., the gangster); has recourse to science fiction and narrative fracture; keeps its eye on the varieties of societal control (family, state, corporation, media); and doesn’t shy away from anything that might be mistaken for sin. Indiana’s also a writer of significant stylistic range. There’s miles between the baroque paranoid pastiche of his most recent novel, The Shanghai Gesture (2010), a heady reimagining of the Fu Manchu in a seaside town afflicted by an epidemic of narcolepsy; and the speedy realism of Resentment: A Comedy (1997), a Dos Passos–goes-to-Hollywood panorama of the Menendez brothers, faded starlets, the AIDS plague, and the dawn of sex on the internet. The sturdy prose of I Can Give You Anything But Love, a mosaic of a nascent writer’s worldly education with occasional outings to the pistol range of memory, falls somewhere in between.

“People like us are lucky because every shitty thing that happens to us is just more material,” Indiana has recalled Burroughs telling him. The first shitty thing, in Indiana’s mother’s view, was “the incident at the lake.” The boy, still short of 10, a child of rural Derry, New Hampshire, was blindfolded, gagged, hogtied, rowed out to the middle of a lake, and abandoned on a raft by a pair of teenage swimming teachers, one of whom, Shirley, had been kind and generous to him all summer. After a few hours of terror and humiliation, they untied him and brought him back to shore. He ran home shaking and “curled up in a fetal clump” under the bed. Indiana himself isn’t so sure that it’s what “flipped me over to the dark side”: “In the 1950s … where I came from, if something awful happened to you, you sucked it up, regardless what ‘it’ was.”

The bigger “it” was his family: his father a drunk and a less than lucky gambler; his grandmother openly cruel; his brother disloyal; an uncle given to teasing him for being insufficiently masculine; his mother kind but weak-willed, provincial, and convinced, when she discovers a notebook in which he’s written an erotic fantasy about another boy, that “an evil outside influence infected me with a disease only psychology can cure.” No surprise, then: “I incessantly hope a different, better family will adopt me.” Instead, he left at 16 for Berkeley, shortly after his bones had grown too big for him to be a jockey at the local racetrack.

Formally, I Can Give You Anything But Love runs mostly on two tracks. Each of its 15 chapters opens with Indiana at work on the book in Cuba, where’s he’s lived intermittently for the last decade and a half. He writes about Havana (“built for giant people with histrionic lives, the bygone lives portrayed in the Brazilian telenovelas everybody watches here”); its nightlife, beaches, and sex workers; his friends and lovers on the island. Like Indiana’s other books, the memoir takes sex as an essential part of life, and his writing about it has a matter-of-fact directness that pays the reader the compliment of being treated like a confidante.

Indiana’s account of his early life picks up “in the long rancid afterglow of the summer of love … The hippie saturnalia had continued as a sinister Halloween parody of itself, featuring overdoses and rip-offs and sudden flashes of violence.” Indiana dropped out of Berkeley and passed through a series of communes flavored with Trotskyites, lectures by Herbert Marcuse, scream therapy, and peyote, until he fell in with Ferd Eggan, a former civil-rights activist and future AIDS activist who at the time was directing a narrative porn film, The Straight Banana, and moved into the commune where Ferd lived with his girlfriend Carol. Ferd was the scene’s charismatic bisexual ringmaster who “shot smack more as a fashion statement than to quell an actual addiction”; Carol “had the vibe of somebody who’d lived the nightmare in a big expensive way … implacable enough to launch a military coup in South America … a vulpine den mother to a shifting cast of acolytes and hangers-on.” The 19-year-old Indiana found himself enthralled with their mix of experience, intellectualism, and avant-garde connections — Carol knew Kenneth Anger and Andy Warhol, and might have been Lenny Bruce’s ex. But some shitty things happened, and after he was raped brutally by a biker in the commune’s basement, he shipped back East.

He didn’t stay long: “Boston. A mean, provincial town with a heart of shit.” It was soon back to California, this time Los Angeles. In his mid-20s, Indiana moved between the punk scene, the gay bars, the piano-bar circuit, a day job at a grim Legal Aid office in Watts, and a night job at a Westwood art cinema. Speed and sex, but also long, solitary spells of reading and fitful attempts at writing. He passed a lot of time commuting on the 101, half out of his head:

I live in a goulash of stalled creative yearnings, surges of paranoia, fits of depression, frequent spells of drugged euphoria. “I” is a blur, something like photo paper in a developing tray. I swallow speed each morning in place of a vitamin pill. I hear voices. I talk into a tape recorder driving to work, preserving logorrheic routines in my head. I’m inhabited by a cast of characters sucked from outer space by amphetamines: a morbidly obese cab driver fond of guava jelly doughnuts who gets his own talk show after running over Al Pacino. Gary X, a gay liberation terrorist recruiting for a Baader-Meinhof branch in California. A jilted studio hairdresser, May Fade, improvises verbal suicide notes, digressing often to recall her work on tragically hirsute or alopecia-stricken movie stars.

In L.A., Indiana lived on the fourth floor of the Bryson Apartments, then owned by Fred MacMurray and possessed of “the seedy desuetude of a James M. Cain novel.” His fellow tenants could have been escapees from the Manson family or a Tennessee Williams play; one expressed a practitioner’s interest in necrophilia; everyone seemed to want to bum a ride. His sometime-boyfriend was an emotionally unavailable exterminator. Ferd and Carol turned up in town, and Ferd talked Indiana into holding a trunk that might have held his radical gay commune’s weapons cache. He landed a little harrowingly in the trash-strewn home of his possibly homicidal speed dealer, and then, finally, after a night on the tiles, in his flipped-over VW on an embankment beside the 101. He climbed out without any broken bones, the cops let him off because he should have been paralyzed or dead (and because drunk driving, when nobody got hurt, wasn’t yet much of an offense), and then he got out of town.

He came to the East Village, where he’s lived most of the last 37 years and made his career, a phase almost entirely elided in I Can Give You Anything But Love (but drawn on as a fictional landscape in early novels like Horse Crazy and recalled in stray essays). The exceptions are spiky portraits of his late friends Susan Sontag and Kathy Acker. Of a preening novelist he and Acker appear with on a PEN panel, she says, “He’s going to pull an American flag out of his ass and fart ‘The Star-Spangled Banner’ in a minute.” Indiana mentions a couple of his and Acker’s “little skirmishes,” but concludes: “Ultimately we were against the same things and up against the same clubby establishment.”

Sontag was a creature of that Establishment, its voracious (usually distant) star-making mascot: “On one hand, I was grateful for a friend whose appetite for reading was even larger than my own,” Indiana writes. “On the other, I found her mentoring urge, expressed in the pushy demand that I absorb any arcane cultural phenomenon she happened to think of, an oppressive generosity.” His catalogue of her flaws is in the end a sympathetic one: After all, it was her “misfortune to live in a country that cares less about intellectuals than it does about the ash content of dog food.”

Or the sort of country that lets Gary Indiana’s novels go out of print. (Semiotext(e) is bringing them back, starting next month with Resentment.) But so it goes. Acker and Sontag are gone; the woods of hardscrabble Derry have been carved up by developers; it’s hard to get beat up on the gentrified streets of Boston; grimy Haight-Ashbury and seedy Wilshire Boulevard have hardened into clichés unlike the pictures you’ll find in this memoir of vanished and unvarnished landscapes. Even Havana, as he writes, is going the way of the iPad and the credit card. Indiana isn’t particularly nostalgic, or particularly proud of his youth: “Like everything irreversible and embarrassing, I’d like to remember it differently.”

*A version of this article appears in the September 7, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.