All week long, Vulture explores what happens to reality TV contestants after the show ends — and the future of the genre itself.

“Picture this: Sicily,” jokes Evan Marriott, invoking Estelle Getty’s signature Golden Girls preamble to set the scene for his surreal experience filming Fox’s Joe Millionaire 13 years ago. Actually, the location was France’s Loire valley countryside, and Marriott recalls that most nights, he’d be sitting with the windows swung open. “I had this beautiful view, and I would sit there every night with a beer in my hand and the phone in my ear. I was talking to a girl named Amy, who I broke up with before I went to do the show, because I was trying to get back together with her.”

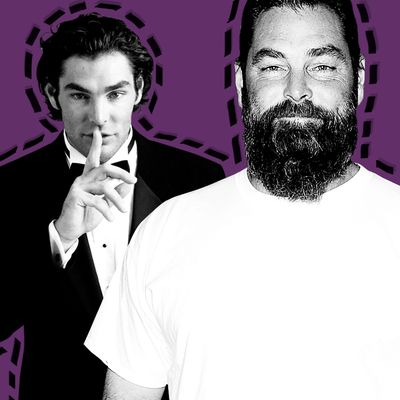

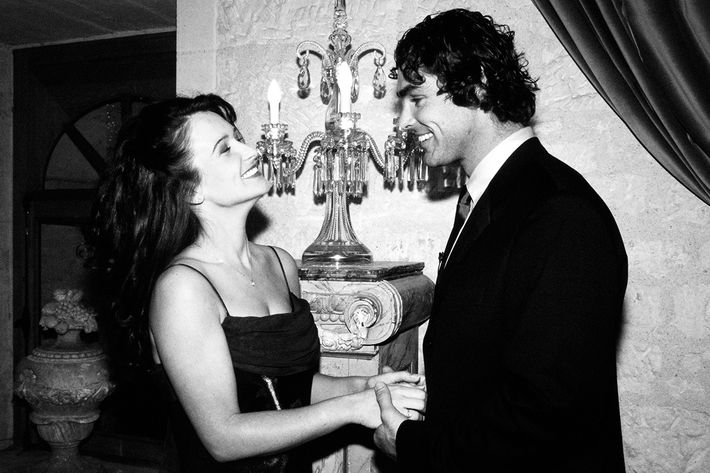

It can’t be, you might say. After all, the whole premise of Millionaire was for Marriott to be wooed by 20 women led (falsely) to believe he was worth seven figures when, in reality, their sugar-daddy dreamboat was a construction worker earning $19,000 a year — not rich, but still hot, at least. Sly and ethically dubious as the final reveal might have been, a nation still watched him and these women go through the now-stock-in-trade routine of heady dates and stolen smooches. And that’s no exaggeration. Millionaire was a transcendent pop-culture phenomenon. Forty million viewers tuned in to the final hour of the February ’03 finale (compare that to, say, the climactic hour of this year’s Bachelorette, which was considered a success by tallying around 8 million), during which Marriott opted to stick it out with contestant Zora Andrich.

“When I signed on to do the show for Fox, reality was very embryonic,” reminds Marriott. The show’s runaway success was held up as a paragon for the burgeoning genre; the media said it marked the “triumph” of reality television as a ratings bonanza for networks. “The goal is to see reality shows affect the entire schedule,” then–Fox entertainment president Gail Berman said after the finale aired. “MTV knew they had something with The Real World, and [there was] Who Wants to Marry a Millionaire, and a couple seasons of The Bachelor, but the social media wasn’t there, and you didn’t have podcasts,” Marriott adds. “It was basically a watercooler thing, so you didn’t know what you were getting into.”

That went for both Marriott and an audience who’d never previously been voyeur to what’s now a customary reality con used on shows like Joe Schmo and I Wanna Marry Harry. It applied twofold for Andrich, who absorbed the truth of her beau’s humble backstory for the cameras in real time, and in doing so, earned a $1 million bounty (which she and Marriott split before going their separate ways). Thinking back to that strange dichotomy of stringing Andrich and her competitors along for the cameras before making clandestine, moonlit calls, Marriott can only figure, “I should have won an Emmy for that dance and kiss with Zora at the end of that show, because all I wanted to do was get back to Amy.”

Viewers — encouraged by tabloid media — made Marriott the fall guy for what was a salacious but unsavory experiment. He was, in essence, a primitive reality villain — a “babe in the woods,” as he tells it — molded and manipulated by opportunistic executives producers and cast out once he’d satisfied his purpose.

He audibly shakes his head recollecting that when he was first approached about Millionaire, “I thought I was doing something like Blind Date.” Once the concept became more apparent, he told producers, “‘I don’t think this is for me.’ That was when they said, ‘We’ll give you 50 grand if you just go with the flow here and do what we say.’ So I said, ‘Okay, fine.’” The resulting hysteria, he avers, “wasn’t anything that I planned. Anybody today that gets into it, they know exactly what they’re getting into.”

At present, a happily single 41-year-old Marriott’s just wrapped a long afternoon under his current, much more comfortable guise: owner of a heavy-equipment rental-contracting company based in Orange County, California, where the Virginia native now resides. It’s the logical extension of his life before Millionaire transformed it. (As for his surprising rare appearance at a reality panel earlier this year, at which he unveiled an impressively grizzly beard and carried an extra few cozy pounds since his trim Fox days, Marriott says he only participated to reconnect with Chuck Woolery*, who gave him instrumental advice amid the Millionaire fallout.) But as a result of the show and all the money and notoriety that came with it, that journey was deferred by a few years of partying, searching for work in show business, and learning just how disorienting life is post–reality TV.

“They absolutely threw me under the bus,” Marriott says of how the network distanced itself from him once Millionaire’s controversial finale generated backlash. “I don’t hold that back at all. The last thing I remember [then–Fox TV Entertainment Group chairman] Sandy Grushow saying to me when I walked in the morning after the season finale [was], ‘Evan, you’re now part of the Fox family. We’re gonna have a great relationship in the coming years, and we’re glad you’re aboard,’ or whatever bullshit he spewed. I was happy, not because I thought they were gonna make me Magnum, P.I. But I thought, At least if they need someone to sweep up a set, I’ll be there, because they basically plucked me out of a life I knew and made me a household name. But, man, two weeks after that little speech, they took my lot pass and I was out in front of the Fox studios with the door slammed in my face. It was that quick.”

Twelve years ago, there was no established exit strategy for someone jettisoned back into public life by the reality merry-go-round. No agents, no sense of how life-altering the aftermath would be. Marriott was arguably unscripted prime-time TV’s most recognizable (and polarizing) face to date, and moreover, people couldn’t seem to differentiate him from the Joe Millionaire persona. After a while, neither could he.

“I was having an identity crisis,” he says. “I wasn’t Evan Marriott, the guy that could go have a casual beer with friends. It’s dissipated, but the first three years, everywhere I’d go [in L.A.], everyone would look up. And what that does is you start to get paranoid. Even though people could have cared less if I got a hamburger or a haircut, I kept thinking, years after the show, somebody’s at my window, somebody’s taking pictures of me, somebody gives a shit about what I’m wearing today. I talked myself into this, and some of it was true and some wasn’t, but it took me a while to talk myself out of it.”

At his lowest emotional point, Marriott compounded that anxiety with a healthy dose of self-loathing and, he admits, “a lot of Scotch.” He resented Hollywood for seducing him, which was complicated by how perversely insulated he felt within its city limits. “When you’re in L.A., if you’re a B- or D-list celebrity, you’re just the next asshole walking through the restaurant.” He found himself desperately thinking, “Somebody give me something. It doesn’t have to be in front of the camera. Something in this business where I can stay in L.A. and be safe in my cocoon.”

In the period between Marriott’s Millionaire run ending (Fox did bring it back for one more low-rated season, with a new Joe) and 2005, he managed to drum up some income starring as himself in various advertising campaigns; appearing at everything from furniture stores to professional conventions to take photos and sign autographs (now a lucrative cottage industry for reality vets); and, in what would be his final flirtation with being an onscreen personality, a fleeting gig hosting Game Show Network’s Fake-a-Date, which Marriott now characterizes as the “worst show ever in the history of television.” One afternoon, after introducing himself to an incoming GSN exec as “Evan Marriott, host of Fake-a-Date,” Marriott claims his new boss replied, “‘Well, about that,’ and he literally fired me as he was unpacking his office.”

That dismissal and his ensuing unemployment constituted, pardon the pun, Marriott’s essential reality check. “I realized, ‘I’m not doing anything in my life, and what the fuck do I do with it?’” he says. “My account is getting low, and I can’t keep drinking every night, drinking every day, spending money [with] nothing coming in.” By 2005, on the advice of a friend, he invested his Millionaire earnings and tangential revenue into his own blue-collar business, finally escaped L.A., and has emerged on only a handful of occasions, largely as an outspoken critic of the unruly genre he unwittingly helped pioneer.

“I was part of what was responsible for it,” he offers, before clarifying that, ultimately, “Fox was responsible. I was their vehicle. They used me and the girls to create all this hype. Fox did a very good job with the buildup to my show, which created a lot of buzz, which in turn created viewers, which in turn created other networks saying, ‘Hey, there’s something to this drama and the thought of these gold-diggers, and we need to take this formula and run with it.’ Producers are the sheep-herders, and we are the sheep. I do feel like we blazed the trail for all this stuff now, and it is a shame that I sit back now and go, ‘God, this is what this all morphed into.’”

Despite his unreserved cynicism about networks and producers, Marriott doesn’t feel compelled to be an advocate for anyone choosing his past predicament. “It takes two to tango,” he puts it bluntly. “If you’re gonna sit there and let somebody take advantage of you, then shame on you. Or maybe you like it. I don’t blame the production company for anything they might have done or not done. I’m a grown man. I had every opportunity to say I did or did not want to do this or that. There’s people I know of who were on reality TV, and when it was over, they stayed in L.A., slept on couches, did whatever they could to get agents, and it’s all because they thought, This is my big break. And they were dirt-poor and miserable because of it, and nothing ever came of it because nobody cares about reality personalities. They’re the redheaded stepchild of TV. It’s sad to think about, but do I really feel that bad for them? No.”

Marriott’s mostly held fast to that conviction over the past decade, even as nostalgia for his generation of reality “pioneers” — e.g., first-ever Bachelorette turned lifestyle maven Trista Sutter — has generated curiosity about their whereabouts. “I’ve been offered all kinds of things as far as interviews and shows, and I’ve said no so much over the past ten years that a lot of people think I’m crazy,” he attests. “I’ve got a good job I can fall back on. If something else comes along, I’ll do it, but I don’t really have to, and I’m not gonna let the media make me look any worse than they did on my way out the door when I last had my opportunity. I think a lot of people aren’t as strong as I’ve been. They’ll do anything. They’ll sell their mother up the river for a shot on TV again. And I don’t really care.”

Marriott’s chief concern by now is returning to his home in Orange County to mind his business, brick-and-mortar and otherwise. And though he’s survived reality infamy intact and urges others to heed his warnings, Marriott realizes that, much as he did, they’re going to have to “learn it for themselves.” Or, failing that, be awfully savvy and thick-skinned. “They have to have a very strong personality,” he implores from a place of hard-earned authority. “Going into reality television thinking you’re gonna do anything on your terms, you’re fooling yourself. When you sign on that dotted line, they own your ass, and they don’t care about you one iota.”

*An earlier version of this piece mistakenly identified Chuck Woolery as Dick Clark.