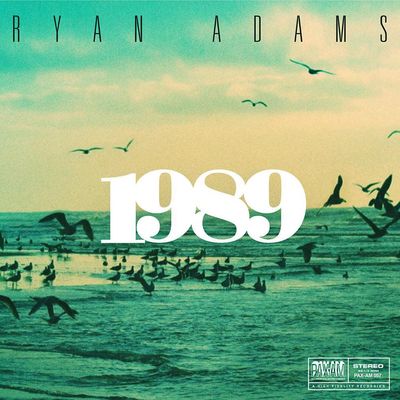

If there’s one song at the heart of Ryan Adams’s 1989, it’s a single not off Taylor Swift’s album of the same name, but rather one from her second album, 2008’s Fearless. “White Horse,” the acoustic ballad that breaks the fourth wall on the storybook romance that propelled her preceding single, “Love Story,” is what triggered Adams’s immense admiration for the then-17-year-old singer. As Adams told Zane Lowe yesterday, it’s near impossible to sing “White Horse” without a lump forming in your throat when the chorus swells. So it came as little surprise to hear Adams explain what drew him to 1989: While the obvious story was Swift removing the country façade in full embrace of dance-pop, all Adams heard “was the emotional content” of the album. Even lyrically, where others focused on diss tracks and “haters gonna hate” anthems, Adams was reminded of what he got out of listening to the Smiths and Hüsker Dü in another part of his life. His goal with 1989, then, especially as he was “going through a hard time” — i.e., getting a divorce from Mandy Moore — was to take these songs that punched him in the guts and make the world see what he saw in them.

Point is, of the many reasons to be a Taylor Swift fan, Ryan Adams is 100 percent in it for the feels. His sad-bastard overhaul of 1989 works as well as it does — and to be sure, it doesn’t in some places — because Taylor Swift, for better or for worse, is the most earnest pop star of our time. That’s the quality Adams heightens in her music, and with any other Swift release before 1989, it likely would not have had the same effect — she provided enough stripped-down feeling right there on the surface. Yet to hear Adams turn 1989’s heavier moments into solid steel anchors into the heart is to reach the rock bottom of his own despair: When he screams, then whispers, “When you’re young, you run, but you come back to what you need” on a gorgeously desperate piano take on Swift’s “This Love,” it doesn’t feel like that much of a stretch. These two are cut from the same emotional cloth.

In fact, the idea that they’d be mutual fans of each other’s work is not terribly surprising at all, despite the internet’s odd initial shock that two heart-on-my-sleeve, formerly-country-tinged singer-songwriters might vibe. If this were 15 years ago, when Adams was still showing rockists that country ain’t all that bad, releasing a full cover album of a global pop icon would be one of the boldest poptimist statements ever made. (Can you imagine if, instead of making Summerteeth, Wilco covered Celine Dion’s Let’s Talk About Love?) But this is nothing that attentive listeners haven’t heard for the last half-decade in our increasingly genre-agnostic musical landscape, one in which indie stars covering chart-toppers is commonplace. Perceptions of ironic intentions are, at this point, more on the listener than the artist.

The difference is that instead of simply forsaking core rock fans who may have held onto their “ew, manufactured pop stars” attitude, Adams invites them along by covering these songs through the lens of the alternative canon: Sonic Youth’s Daydream Nation gets a shout-out on “Style” instead of James Dean; the Smiths and the Cure are obvious reference points on certain songs; and there’s no shortage of classic alt reverb. In the process, Adams toys with listeners’ perceptions of authenticity. While big pop isn’t necessarily relegated to guilty-pleasure status anymore, rock and roll still has a historical monopoly on “realness.” By taking the basic structure of Swift’s songs and dialing them way back in instrumentation and production, Adams is at once affirming these beliefs about musical authenticity and dismantling them: These songs were here all along, he’s telling the pop haters, and Taylor Swift wrote them. Mostly, he’s taking us back to a time when pop and rock could exist synonymously. His biggest influence here, the Smiths, are the masters of the pop-rock split: rock’s raw emotion in the lyrics, pop’s undeniable hooks in the chorus; neither more important than the other.

If you’re coming into this as I suspect a fair number of listeners are — having heard 1989 at the time of its release and being at least peripherally aware of Ryan Adams’s whole thing — you’re basically getting a brand-new experience with an album you already know the words to, which can be pretty fun. The songs on Swift’s original that sound like nothing special, or even downright cloying, are improved under Adams’s watch. What was once an opening track skipped by default (and embarrassing as a New Yorker), “Welcome to New York” is made at least tolerable via Adams’s semi-unintelligible Springsteen warble; “Shake It Off” is given a quirky little Postal Service–style synth line and transformed into a compelling anti-anthem about someone battling demons by dancing alone in the dark while repeating a comically lighthearted mantra under his breath.

And the opposite is also true: Songs that Swift made distinct are forced into different styles that feel far less original. “Out of the Woods,” with its vertigo-inducing onslaught of electronics, is transformed into a “Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want”–style play for slow-dance nostalgia. Similarly, the sinister beats (well, for Taylor, at least) that made “Bad Blood” feel wholly different from the rest of her catalogue (save for “I Knew You Were Trouble”) are replaced by coffeehouse-singer-forcefully-covering-“Wonderwall” strumming and a jangly counter-melody in the chorus that hints at Johnny Marr’s sensibilites. There’s a little overlap, too: “Style” is glorious on both versions of 1989, as a slicked-back ‘80s synth-burner from Swift, and a Stones-style rock boogie from Adams. Like Swift, Adams has moments on 1989 where he sounds like a parody of himself, and others where he doesn’t really resemble his past work.

Far more than his peers, Adams is the guy who runs back into the studio seemingly every time he’s got something to say. It’s why his discography spans so many different styles, and why the most common critique of his work is that he lacks editing foresight. As Adams mentioned on Beats 1 yesterday, his 2014 breakup inspired a forthcoming double album in the vein of 2004’s Love Is Hell; afterward he still had emotion to spare, so he poured it into reimagining 1989 as something quite different. Depending on how you look at it, his exercise is either the musical equivalent of those pointless but nonetheless amusing movie-trailer recuts that frame, for example, The Shining as a vacation comedy (Father John Misty hammered this particular point home with his parodies), or it’s a touching statement on how fans use music as a salve for life’s bruises and scrapes. To me, it’s a bit of both — but not some grand plan to unite the pop and rock worlds. Ascribing such a lofty purpose to the project is a big part of why it’s easy for one half of the internet to think this was the greatest idea ever, and for the other half to still be rolling their eyes over it. Then again, when a project involves Taylor Swift, that’s the most-likely outcome anyway.