The madly (as in angrily) prolific Alex Gibney is back with another provocative doc on someone who has had more impact than Julian Assange, Lance Armstrong, Tom Cruise, and almost anyone else whom Gibney has profiled put together: the demigod Steve Jobs. The movie — Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine — isn’t exactly a takedown, although anything less than worshipful of Jobs and the world he ushered in will be experienced as such. It’s a skeptical essay, a meditation, a corrective. Gibney makes a reasonable case that the man who presented himself as a counterculture Zen visionary striking a blow for individualism and freedom was a more ruthless and powerful species of capitalist than most who’ve walked the Earth. Little here is new, but the archival footage is well chosen, the interviewees are illuminating, and Gibney, as usual, potently synthesizes what’s out there. He also knows enough to throw a spotlight on what can’t be synthesized: the contradiction between everything Jobs strived to be/said he was/thought he was and the harsher reality.

Not so by-the-way, I’m typing this review on a MacBook Pro, on which I watched Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine via an internet link. I’ve been a Mac guy since the early ‘80s, seduced by the ease of the machines (no MS-DOS or other computer language to learn) and also by their futuristic elegance. I was in the cult long before the iPod or iPhone and I’m still in it, although at this point by default. Gibney begins the film by giving you a sense of how vast that cult is. It’s October 2011, on the day of Jobs’s death, and men and women stand solemnly in front of Apple stores holding up iPads with candles burning on the screens. Little kids deliver online paeans to Jobs’s genius. The names of Einstein, Bob Dylan, John Lennon, and Martin Luther King are invoked. Gibney observes in voice-over that this is an unusual response to the death of a businessman whose chief motivation was, in the end, making himself and his shareholders rich(er). He then goes on to probe the extraordinary attachment we’ve collectively formed with this brand and its public face.

The young Jobs saw early on — not earlier than some scientists but way ahead of business leaders — that computers could bring about a paradigm shift that would, he said, “outstrip the petrochemical revolution.” But he also intuited something about that technology that few outside the realm of sci-fi considered: that a computer could be sold not as a piece of technology but as something positively intimate. This is you, he said. And the company that gave you yourself wouldn’t be impersonal, faceless, like the giant IBM. Its name would come from nature. (Was the tree-of-knowledge connection intentional? Unclear.) Apple’s distillations/enlargements of you would be colorful, personal, made by artists whose names Jobs had etched on the inside of the hard plastic case. The company’s 1984 commercials explicitly invoked 1984. In this seductive scenario, bold individualists would liberate you from a depersonalized, robotic, Orwellian IBM future.

Gibney charts Jobs’s rise with an emphasis on his genius for creating a brand, but with many shuddery digressions about his treatment of colleagues and employees. Tasked by Atari with his pal Steve Wozniak (somewhat undercovered here) to develop quickly a more complex Pong, he split the payment 50/50. Unfortunately, he told Wozniak that the payment was $700. Woz would later learn it was $5,000. It’s the first of many times you think, What an asshole. Still visibly shattered, Bob Belleville speaks of the soul-consuming nature of the early days and the loss of his wife and family. Although worth $200 million in the early ‘80s — when that was real money — Jobs agreed to pay only $500 per month in child support for his first daughter and, when challenged, denied paternity, insisting that he was infertile. (A DNA test proved that he was, indeed, her father. And he wasn’t infertile by a long stretch.)

Jobs’s fervent Japanese aesthetic — which helped to give Macs both their clean, elegant lines and often blobby shapes — led to a lifelong search for enlightenment, which brought him to the doorstep of the late Zen priest Kobun Chino Otogawa. In archival footage, Otogawa recounts Jobs’s eager pleas to become a monk and Otogawa’s dubious response. “He’s brilliant but too smart, I think,” says the sensei. It’s a line that the whole movie seeks to unpack. Claiming to cultivate an inner calm, Jobs ruled by chaos, says one colleague — “seducing you, vilifying you, ignoring you.”

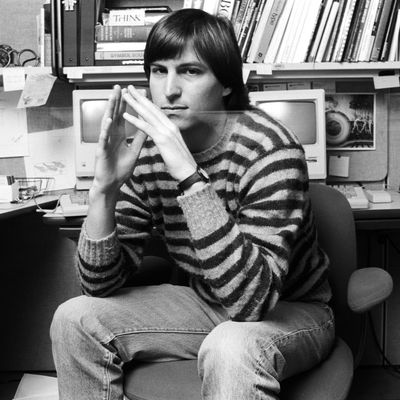

Footage of him from all periods shows the same hungry, wolfish countenance and predator’s awareness of everything in the room. Under the movie’s sway, you might begin to see Satan in that visage.

It isn’t until the last 45 minutes — Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine runs over two hours — that Gibney hauls out the big guns and challenges nearly every aspect of Jobs’s meticulously constructed brand. When Jobs returned to Apple after a ten-year exile (during which he started Pixar, among other things), his countercultural, humanity-liberating posture existed side-by-side with axing all Apple’s philanthropic programs, colluding with other Silicon Valley giants not to hire away one another’s employees, underreporting profits, channeling more than $100 billion into Irish shell companies to keep from paying U.S. taxes, and backdating stock awards. Gibney and his interview subjects (among them Peter Elkind, Andy Serwer, and Joe Nocera) make it pretty clear that Jobs lied and kept lying (there is footage of him in a deposition pretending to be vague on the subject of accounting) and that he would have gone to prison had he not been the most indispensable person in the Valley’s — maybe the country’s — most indispensable company. He was too big to prosecute.

China … well, you probably know all that. But the accounts of explosions, individual and eco poisonings, and suicides associated with Foxconn get a fast going-over. Apple makes $300 in profit on every iPhone but won’t endanger share prices to ensure Chinese workers a decent wage. Nocera says when you write about this stuff, you get threatening emails — not just from Apple but from people who “love the company.” Not that Jobs didn’t make threats — and act on them. Just ask the Gizmodo editor whose door was bashed in and computers appropriated by a special task force. Jobs ended his life by telling lies about the diagnosis and treatment of his cancer. Maybe he believed them. He had, many say, a reality-distortion field.

Gibney gives Sherry Turkle a good platform for promoting her book, Alone Together, about the isolating effects of social media. This is a subject worthy of much more time than Gibney gives it — he too readily assumes we agree. (I do, somewhat, but the jury is still out.) But his coda is remarkably effective. As his camera prowls Japanese gardens and shoji screens, Gibney describes Jobs as, among other things, a man who sought but never found inner peace, who had “the focus of a monk but not the empathy … [who offered] us freedom but only within a closed garden to which he held the key.” Gibney still bows down before Jobs’s mystery — and the mystery of why so many of us felt a religious connection to “the man in the machine.”