This post originally ran on September 25. WeÔÇÖre resurfacing it to correspond to the release of The Martian.

ThereÔÇÖs a specific moment that happens on some of the better reality-competition shows, when the seasonÔÇÖs big villain is eliminated and the other contestants can finally get to work. ItÔÇÖs the point where you realize that you like everybody whoÔÇÖs left, and whatÔÇÖs even better is that they like each other, too. ItÔÇÖs become an unmitigated pleasure to spend time with these talented people, and now that the camera-hogging villain is gone, thereÔÇÖs more room to showcase what it is they do best.

You donÔÇÖt often get moments like that in the movies, where slavish adherence to the three-act formula means that most films will feature an asshole antagonist, a conflict between our heroes, a misunderstanding that leads to a dark night of the soul, and a reconciliation that happens only at the end. If youÔÇÖre looking for simple, pleasurable scenes where the characters get along and thrive in their work or love lives, your best option is to imagine what comes after the closing credits, because once most movies vanquish their villain and exhaust their amped-up central conflict, theyÔÇÖre over.

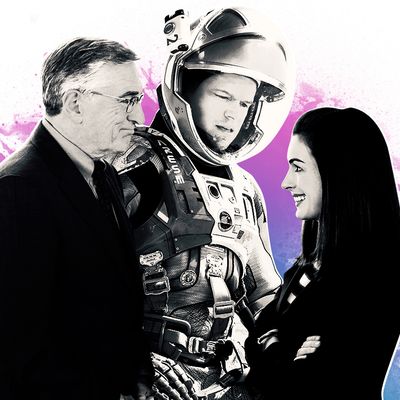

Imagine my surprise, then, to find that two of this fallÔÇÖs biggest movies go about things in a different way. A sweet comedy like The Intern and a space adventure like The Martian might not appear at first to have much in common, but theyÔÇÖre both fairly radical in the way that they circumvent a modern moviegoerÔÇÖs expectation of conflict. In the age of the antihero, these films are entirely populated by nice people, and the protagonists donÔÇÖt labor mightily over two hours to become better, or even decent: TheyÔÇÖre already pretty great, and thatÔÇÖs the reason why youÔÇÖre watching them! Since both films eschew a villain, it gives you ample time to exult in these talented folks, who are fond of each other and excellent at what they do. Both movies are such a pleasure that after watching them, I started to wonder: Is conflict overrated? In the age of the antihero, I thought, maybe we just need more movies about nice people doing nice things.

ItÔÇÖs not as though thereÔÇÖs no conflict at all in The Intern (written and directed by Nancy Meyers), but to some, it might seem like the protagonists are facing nothing but Champagne problems. Robert De Niro plays a sweet-hearted, successful widower whoÔÇÖs simply looking for a nice 9-to-5 gig to lure him out of retirement, while the dot-com boss he goes to work for, Anne Hathaway, is successful, wealthy, and well-liked. The conundrum sheÔÇÖs grappling with is whether to bring in a more experienced CEO to serve above her, but the fate of her company does not depend on the decision, and thereÔÇÖs no underling trying to sabotage her; instead, all she has to mull over is whether she wants to relieve some of her workload at the expense of her sole ownership. Both protagonists, then, are simply trying to figure out the best way to spend their time, and there are far worse ways to spend your own than watching them figure out their lives with proficiency and kindness.

The scene that best showcases The InternÔÇÖs warm, unconventional attitude comes halfway through the picture, after Hathaway has accidentally assigned De Niro to another department. TheyÔÇÖve grown to really like each other, but Hathaway had forgotten about the transfer request sheÔÇÖd put in earlier, when she was more skeptical of De NiroÔÇÖs presence in her office. Now that heÔÇÖs become an indispensable confidante to her, heÔÇÖs gone. I braced myself and did the motion-picture math in my head: Right on cue, the misunderstanding had arrived that would split our bonding protagonists apart, and an explanation, proof of devotion, and rapprochement would take at least 15 more minutes of screen time. That irritated me. I wanted to go back to the way things were, when there was no plot point introduced only to sever the pleasure of Hathaway and De NiroÔÇÖs company.

I shouldnÔÇÖt have worried. In the very next scene, after Hathaway realizes that De Niro has been transferred, she rushes to find him in a coffee shop and explains herself. De Niro is nonplussed. He still likes her, and he understands the mistake. TheyÔÇÖre friends again ÔÇö it was that simple. In a scene like that, some filmmakers would be too abashed to give the audience what they wanted. Nancy Meyers, on the other hand, has made a career out of it.

The same canÔÇÖt be said of Ridley Scott: In most of his recent films, Scott has defiantly stymied audience sympathies by filling his casts with characters who are near-impossible to root for. Everyone is an aphorism-spouting moral muddle in The Counselor, while the crack team sent into space in Prometheus is comprised mostly of jerks who touch things they really, really shouldnÔÇÖt. ThatÔÇÖs why ScottÔÇÖs new film┬áThe Martian┬áis so startling: The filmÔÇÖs ensemble features over a dozen notable characters, and not a single one is a prick.

The central conflict in The Martian is far bigger than the company quandaries of The Intern ÔÇö Matt DamonÔÇÖs astronaut has been stranded on Mars during a mission gone wrong, and must struggle to stay alive while NASA figures out a away to save him ÔÇö but the people in it are no less decent. Damon doesnÔÇÖt have to resolve some sort of a personal failing in order to self-actualize on Mars: He just has to use his formidable brain whenever thereÔÇÖs a problem. Back on Earth, NASA officials have different ideas for how to rescue Damon, but thereÔÇÖs no penny-pinching, officious bureaucrat whoÔÇÖd rather leave him to die. Even the crew that accidentally strands Damon is empathetic: You would have made the same decision they did, and when a dangerous scheme is suggested that will allow them the chance to right their wrong, not a single brave astronaut declines it. These are great people doing smart things to help each other. ItÔÇÖs kinda nice!

And while the whole stranded-on-Mars thing presents a high-stakes problem for Damon, the film never slams down on that pedal too hard. Every time a new problem crops up, Damon or his support crew promptly figure out an ingenious way to circumvent it. The obstacles here arenÔÇÖt meant to build and build to a point of unbearable tension. Like the challenges on a good, early episode of Project Runway, they simply serve as the impetus for unconventional problem-solving, and itÔÇÖs invigorating to watch these characters work at the top of their abilities: When Damon faces a particularly daunting problem, he grits his teeth and says heÔÇÖll have to ÔÇ£science the shit out of this.ÔÇØ What is that line but a more expletive-laden version of Tim GunnÔÇÖs famous Project Runway motto, ÔÇ£Make it workÔÇØ?

I found both The Intern and The Martian a total pleasure to watch, but some people donÔÇÖt know what to make of movies like this: TheyÔÇÖre conditioned to expect conflict, and lots of it. Reviews have been mixed for The Intern ÔÇö ÔÇ£drama often is shortchanged,ÔÇØ wrote one disappointed critic for The Hollywood Reporter ÔÇö and while most moviegoers at the Toronto Film Festival went gonzo for The Martian, I still talked to a few people who felt the movie went down too smooth. They expected a bad guy, or a supporting cast culled down by just-for-the-sake-of-it deaths. Without the usual signposts, they were as adrift as Matt DamonÔÇÖs astronaut.

But sometimes itÔÇÖs nice when you donÔÇÖt know what to expect. Too many movies model themselves after existing works, resulting in conflict-laden characters and plot points that feel derivative; meanwhile, too few movies present the people we aspire to be like and give us the exceptional escapism that we want out of cinema. I like a good antihero as much as the next guy, but both real life and cable TV are now filled to the brim with people making moral compromises. Maybe itÔÇÖs more daring just to be good.