It has been a rough year for makers of original media, with the increasing use of generative AI threatening the livelihood of writers, editors, and artists of all kinds as well as the intelligence of readers. What a joy it is, then, to consider the books of 2024, the best of which have a specific point of view that is robotproof: a unique perspective on what it’s like to experience the world in all of its sorrow and wonder.

10.

Colored Television, by Danzy Senna (Riverhead)

Selling out isn’t as easy as it looks. When her agent and editor reject her epic second novel, “a four-hundred-year history of mulatto people in fictional form,” financially struggling L.A.-based writer Jane trashes it (along with her moral and aesthetic principles) in favor of pitching a sitcom about a “kooky but lovable mulatto family.” Perhaps here, she thinks, is a way to package the topic of racial identity palatably enough for the American public. Yet the TV world isn’t as welcoming as she’d bargained for. In this scathing yet mirthful satire on race and art-making in America, underappreciated author Danzy Senna finds the darkest of humor in the realities of creative life.

➼ Read Madeline Leung Coleman’s review of Colored Television.

9.

The Coin, by Yasmin Zaher (Catapult)

Yasmin Zaher’s debut novel follows the schemes and obsessions of a young Palestinian teacher living in Fort Greene as she begins to lose the plot in her daily life. The unnamed narrator finds affirmation in the designer labels and luxury items that surround her, the spoils that inherited wealth brings. But no amount of intense exfoliation or other fastidious grooming and cleaning can slough away her inner conviction that she is filthy, a “dirty Arab,” as she at one point calls herself. With its dry wit and devastating final pages, The Coin is an ugly and beautiful addition to the mini-canon of Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown novels from Plath to Moshfegh.

8.

The Freaks Came Out to Write, by Tricia Romano (PublicAffairs/Hachette)

If you haven’t heard, the media are in trouble, with billionaire moguls chipping away at the integrity and stability of journalism. It feels poignant, then, to allow oneself a dose of nostalgia for the age of alt-media when The Village Voice was at the pinnacle. Tricia Romano’s oral history of the independent downtown NYC paper covers a who’s who of influential culture writers like Vivian Gornick and Hilton Als, Stanley Crouch and Ellen Willis. Romano pays tribute to the paper’s history without idealizing a moment; sometimes, just a clever juxtaposition of quotes points readers toward the infighting, the tonally obtuse managerial decisions, and the writerly rivalries (and so much sex with co-workers!!) that pervaded the Voice. What results is a gossipy, essential history of a media institution that challenged the status quo, at least for a little while.

7.

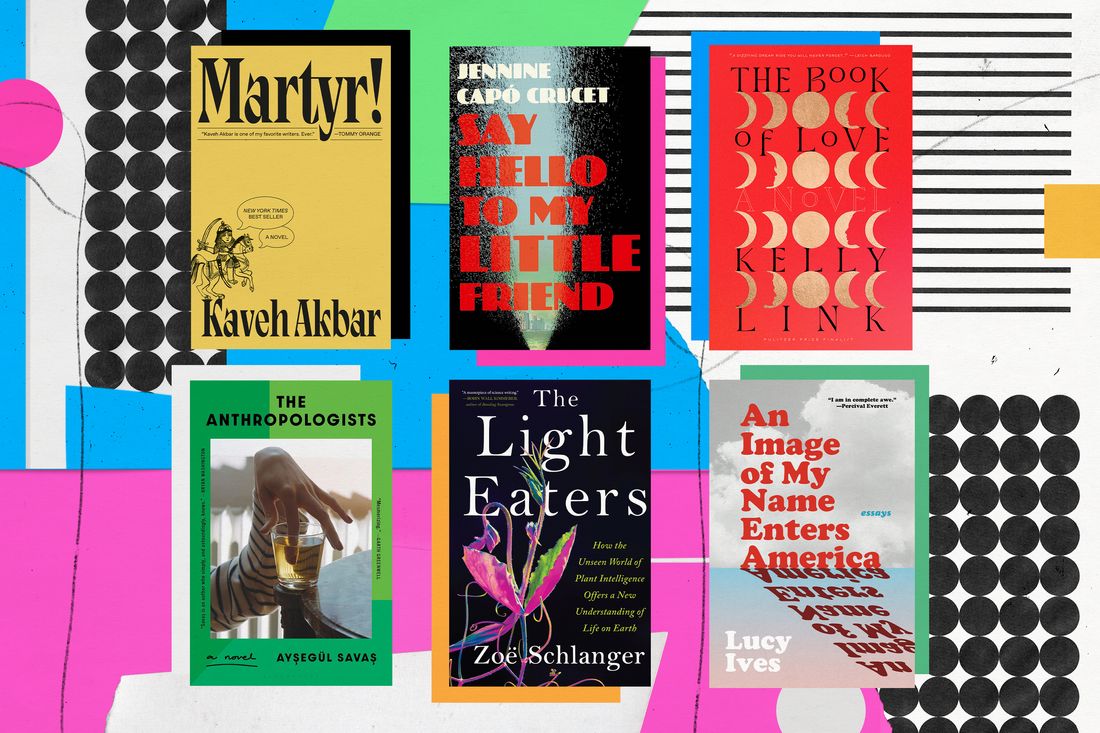

Martyr!, by Kaveh Akbar (Knopf/PRH)

An energetic novel bursting with big ideas, Martyr! tells the story of Cyrus Sham, an aspiring writer and former addict who has multiple obsessions: the deaths of his parents, his Iranian heritage, how to create art that matters, and how to know what’s worth dying for (or maybe even living for). With these thoughts in mind, he takes an impulsive trip to New York City to see a conceptual artist in the style of Marina Abramovic, whose final project is to spend her last days living inside the Brooklyn Museum before she succumbs to cancer. Told primarily from the perspective of Cyrus’s overactive mind, Martyr! includes multiple points of view from his family members and friends as well as passages from his work in progress: The Book of Martyrs. If the plot of poet Kaveh Akbar’s first foray into long fiction verges on the chaotic (in the best way!), then his dazzling prose is what keeps it grounded. Bonus tip: The audiobook version, narrated by Succession’s Arian Moayed, is exquisite.

6.

The Light Eaters, by Zoë Schlanger (Harper)

Woe to an environmental reporter in the 21st century with new climate-change-related catastrophes seeming to arise daily. After suffering burnout from her reporting job, Zoë Schlanger, now a staff writer at The Atlantic, took time off from work in order to study plants and fall in love with the physical world in a way she hadn’t before, one that requires deep noticing of our surroundings. Even if plants don’t have eyes, ears, and brains as we know them, she wondered, does that mean they can’t feel? Can’t communicate with one another? Can’t hear? Can’t remember things? The more Schlanger learns about the work of some of the most unconventional and enterprising botanists of today (Robin Wall Kimmerer makes a memorable appearance), the more difficult it is to distinguish the human world from the plant world: “A wall I’d unwittingly constructed between the two was getting thinner, more transparent, like the wet membrane of a soap bubble threatening to tear. Hard green buds were poking through.”

5.

Say Hello to My Little Friend, by Jennine Capó Crucet (Simon & Schuester)

A maximalist novel with an audacious premise, Say Hello to My Little Friend absolutely shouldn’t work; there’s simply too much going on. It’s the story of Ismael “Izzy” Reyes, who flees Cuba for Miami as a child and then briefly becomes a Pitbull impersonator in his early 20s (the titles of each section of the novel are Pitbull albums and songs) before deciding to try to live his life like his cinematic hero, Tony Montana. Meanwhile, in the midst of trying to pull a Scarface (or at least to do the first half of the film), Izzy makes a spiritual connection with an orca named Lolita living unhappily at the Seaquarium, and their fates become intertwined. All of the strands of Say Hello to My Little Friend come together brutally yet tenderly, for that rare kind of book that makes profound political statements about the nature of borders and captivity yet still manages to brim with jokes.

4.

There’s Always This Year: On Basketball and Ascension, by Hanif Abdurraqib (Random House)

The literary equivalent of a gravity-defying slam dunk: How lucky we are when a masterful writer of prose (and a poet) takes on a familiar subject, in this case, basketball, and lets us see it through their own discerning eye. Hanif Abdurraqib spent his childhood on the neighborhood courts in Columbus, Ohio, with all of the mythology that surrounded them, and he places his own experiences parallel to the rise of local hero turned international superstar LeBron James. Structured around a basketball game with the clock ticking down second by second, There’s Always This Year takes frequent digressions that turn out to be much more than mere asides; they add to the crux of what turns out to be a propulsive treatise on who gets to succeed and on what terms, delivered with the grace and agility of the most virtuosic athletes.

3.

The Book of Love, by Kelly Link (Random House)

The escapist masterpiece of the year. Kelly Link has been writing exquisite, fantastical short stories for years, so it was a new delight to see her take on capacious, messy, and magical subject material in her supersized debut novel (it’s 642 pages). With the precision of a short-form writer and the imagination of the best kind of fabulist, Link transports us to a small New England town where a trio of teenagers are there but not — they’re caught in a liminal space somewhere between life and death — and the high-school music teacher who may just know how they got there and how they might get out. We follow their trials (literally, they must complete a series of trials to return to their loved ones) as Link pulls back to reveal a greater battle between good and evil beginning to bubble up all around them.

2.

An Image of My Name Enters America, by Lucy Ives (Graywolf)

My favorite kind of writing is the kind that, through the seamless blending of high and low culture and all the beautiful muck in between, shows how everything is connected: our personal biographies, the art we consume, literary theory and philosophy, and historical context. It is a pleasure to follow Lucy Ives’s big, dazzling brain in this collection of five interconnected essays as she takes us from My Little Pony and Alanis Morissette to Lacan, Derrida, and Freud to cover topics like the insufficiency of language in talking about mental illness and the ways pregnancy and birth are an affront to reason. Part criticism, part personal essay, part intellectual jubilation, An Image of My Name Enters America is the most inventive and exciting work of nonfiction this year.

1.

The Anthropologists, by Aysegül Savas (Bloomsbury)

2024 was the year of the breakup book; you couldn’t encounter the new-releases table at the bookstore without running into a flurry of wonderful, fucked-up novels and memoirs in which emotions run high and the fights are epic. Here is an antidote. Turkish novelist Aysegül Savas’s third novel follows a couple in an unnamed city in an unnamed country where neither was born as they experience the quiet yet colossal beauties of their daily lives. Manu and Asya’s concerns are modest: to find community in the absence of their biological families, to look for an affordable yet homey apartment, to pursue creative endeavors, and to eat and drink a bunch. It’s a joy to be on this journey with them. Each sentence sings, and watching Manu and Asya find a home in each other rather than in the places they’ve been is defiantly, explicitly hopeful.

Other Book Highlights From This Year

Throughout 2024, Vulture contributors maintained a “Best Book of the Year (So Far)” list. Some of those selections appear above in our top-ten picks; below are more books (but not all) that stood out to us this year, listed by U.S. publishing date with the newest releases up top.

My Lesbian Novel, by Renee Gladman

Renee Gladman is one of the most unclassifiable writers working today. Her latest novel is a conversation between an author and an unnamed interviewer about the author’s attempt to write a lesbian genre novel. Excerpts from the unfinished novel appear regularly in the text between reflections from the author about her process writing the book and her views on the genre. Page by page, though, the conversation about the unfinished book itself becomes the novel Gladman is trying to write. It is a disorienting and thrilling revelation, one that reshapes the entire book that precedes it. For Gladman, the book is a sentient creature: “We walk the woods or leave for vacation without telling the book, either of the books, but I think about the book the whole time I’m away.” Her process is one of connection between author and book and world, where all are constantly influencing each other’s growth. My Lesbian Novel is an acrobatic book, as brilliant as it is erotic. It’s hard to think of another writer who might pull this off. —Isle McElroy

Small Rain, by Garth Greenwell

Garth Greenwell’s first two books — What Belongs to You and Cleanness — highlighted the author’s masterful descriptions of intimacy and sex. In his latest novel, Small Rain, Greenwell writes about a kind of embodiment stripped of pleasure: illness. After nearly dying at home, a poet endures a prolonged stay in the ICU during the early days of the pandemic, where he is forced to cede control to the staff at the hospital. For as powerfully as Greenwell writes about the physical pain of sickness, what stands out most is his attention to the mind. Greenwell’s sentences deftly capture the twisting abstractions of thinking through pain, the desire to be anywhere else instead of becoming an object of study for strangers. A doctor’s last name is enough to send the narrator into a searching meditation on Mahler: “[The song] didn’t just light some chamber of myself that had been dark, it made a new chamber, somehow, it made me capable of some feeling I couldn’t have felt before.” Small Rain is a wise, humbling novel full of longing and grief that plumbs the uncomfortable depths of being alive. —I.M.

Creation Lake, by Rachel Kushner

Fresh off a botched assignment for the U.S. government, a newly freelance spy makes her way to a small town in France to meet the charismatic figurehead of an anarchist commune. The group may have plans to disrupt a government project, and Sadie Smith has been hired by an unknown client to figure out its intentions — or, perhaps, to stir up trouble from within. Compared to scheming, keen-eyed Sadie, everyone she meets seems hopelessly naïve: the bickering anarchists, the comically resentful commune dropout, the man Sadie married to gain access to the group. Her only true equal seems to be Bruno Lacombe, a much older intellectual who has chosen to live an isolated life in a network of caves nearby. Kushner’s new novel, after 2018’s The Mars Room, is the kind of highly satisfying literary thriller that always seems in short supply. —Emma Alpern

Highway Thirteen, by Fiona McFarlane

Each of the characters in Fiona McFarlane’s short-story collection Highway Thirteen are linked to Paul Bigba, a fictional Australian serial killer. Not all victims, they each process their own anxieties and obsessions by way of the killer’s crimes and violence. Despite the subject matter, not every story is serious. It’s funny (and surprisingly accurate) to read a transcript of a pair of feminist true-crime podcast hosts discussing a recent development in the killer’s case or a story about a couple that is upset that the killer’s eventual death is overshadowed by the rise of COVID-19. And in “Hostel,” one of the standouts of the collection, a woman obsessively recounts the story of her friends who saw a news report of a victim’s death and connected her picture to a woman they nearly (or supposedly, who knows) took in months before (though memory is tricky, you know). After the friends eventually separate, the narrator is desperate to hear the story one last time: “It felt as though this might be my last chance to get close to the largeness of life, its terror and mystery, while remaining perfectly safe.” —Ashley Wolfgang

God of the Woods, by Liz Moore

When Barbara, the 13-year-old daughter (and first-time camper) suddenly vanishes from the camp her family owns — and her brother disappeared from 14 years earlier — a rookie small-town detective attempts to uncover secrets the community can’t seem to escape. We never hear from Barbara herself; her story is instead told over the span of 25 years from the perspectives of everyone around her.

Very early on in God of the Woods, a camp counselor tells the story of Pan, the Greek “god of the woods”: “He liked to trick people, to confuse and disorient them until they lost their bearings, and their minds.” There’s no magic here, nor an ounce of paranormal trickery; it is mythical, though, in a way that local legends will never fail to fuel the campers. More than a mystery (although the twists are delicious), what makes the book shine is how each of the multilayered perspectives work together to capture how the family dynasty that owns the camp, the teenagers that attend, and the community working for them all tragically fail each other as they yearn for a second chance. —A.W.

Bear, by Julia Phillips

Off the coast of Seattle exists an archipelago where Sam and her elder sister Elena have spent their entire lives. Their days on San Juan consist mainly of catering to wealthy tourists in order to make ends meet and caring for their terminally ill mother, and Sam copes by dreaming of the day she and Elena can finally leave the island and start anew. So passes the first two-thirds of Bear: an unhurried, intimate portrait of sisterhood, inherited trauma, and the monotony of poverty in a society emerging from a pandemic. But a glimpse of a new life (and a not-so-subtle representation of the threats that lie beyond the islands) arrives on San Juan in an unexpected form: a wild grizzly bear in transit. Elena, captivated, and Sam, terrified, must now contend with the new presence. A rapid escalation of events ensues as the sisters’ drastically different yet equally ill-advised approaches to the unexpected visitor lead to devastating consequences. Bear may be a slow burn, but by the final chapter, Sam’s whole world is engulfed in flames. —Anusha Praturu

Parade, by Rachel Cusk

In an interview with The New Yorker, Rachel Cusk said she believes character no longer exists. That a person — an author or their fictional creation — should be constrained by their name, their past, and their habits is an old conception that’s wearing away, and good riddance. This view governed her Outline trilogy, which shows its narrator in relief, standing apart from the people she talks with, both peers and strangers. In her latest novel, Parade, Cusk takes her belief in the death of character even further as a cast of voices, many of them named G, wax philosophical about their spouses, avant-garde painting, and a random act of violence. Formally frenetic and sharp line by line, Parade doesn’t mimic decades-old experimental modes. (Renata Adler’s Speedboat comes to mind at times, though.) Instead, Cusk has written something genuinely new — again. And whether Parade is a character-driven story in spite of itself is an open question as exciting as its mutable storyline. —Maddie Crum

➽ Read Andrea Long Chu’s review of Parade.

Sex Goblin, Lauren Cook

When Lauren Cook publishes a new book, it is like a minor holiday to me. Cook is a trans naturalist and writer who came up on the Tumblr-era internet; his previous book, I Love Shopping (2019), is sold out and impossible to find — if you have my copy, please give it back. His latest, Sex Goblin, is a collection of poetry and short prose that read like posts on a porn sub-Reddit until you realize your guts are on the floor. In a sparse, direct, half-naïve first-person idiom, there’s an emotional acuity that sneaks up on you, making the mundane (waiting in a drive-through at Starbucks) and the surreal (a witch who turns an offending man into underwear) feel unpredictable and immediate, like the rumbling before an earthquake, when the ground might crack open. —Erin Schwartz

Wait, by Gabriella Burnham

After the success of her debut novel, It Is Wood, It Is Stone, Gabriella Burnham returns with an emotionally grounded political novel. When out dancing with friends, Elise learns from her younger sister that their mother has disappeared. Elise returns home to Nantucket Island, where she soon discovers that her mother was arrested and deported to São Paulo, after more than two decades away from Brazil. As Elise struggles to bring her mother back, she falls in with her wealthy best friend, who has recently inherited her grandfather’s mansion. No matter how close the two friends may have been, there remains an unbridgeable class divide. Burnham is a skilled observer of the hypocrisies coursing beneath our desire to do good and be good. This is especially clear when she writes about wealth. Wait is an empathetic and clear-eyed exploration of the everyday injustices that slowly erode friendships, families, and lives in America. —I.M.

All Fours, by Miranda July

An artist of niche celebrity plans to celebrate her 45th birthday by driving alone across the country, from L.A., where she lives with her husband and child, to New York. But when it comes time to hit the road, she finds herself stopping in a nearby suburb, meeting a younger man who works for Hertz, and spending the entirety of her vacation in a motel, which she renovates to Paris-inspired perfection for the cool sum of $20,000. It’s not just that Miranda July’s latest novel is so propulsive you might have to cancel plans or set aside PTO just to scarf it down. It’s that her dazzlingly horny intelligence wrestles with marriage, queerness, and desire in ways sweet and hilarious, making even the smallest sizzle. —Jasmine Vojdani

➽ Read Christine Smallwood’s review of All Fours.

Ghostroots, ’Pemi Aguda

The 12 stories in ’Pemi Aguda’s mesmerizing and unsettling debut collection, Ghostroots, revolve around life in Lagos, the author’s home city. Aguda is a precise and exciting prose stylist, and her stories offer vivid insights into tradition, family, and trauma. Throughout the collection, the past invades the present, in the form of unwanted lineages and regretted decisions. A woman who cannot produce milk for her newborn blames herself for this ailment. The child was conceived the evening she forgave her husband for having an affair — she believes she’s being punished for being so forgiving. In “Manifest,” a young woman who resembles her grandmother — an evil woman, she is told — begins to adopt her grandmother’s most terrible traits, leading to an act of violence she cannot take back. The horror in Aguda’s stories are borne out of a sense of inevitability. Her characters, unable to change the past, are forced to confront futures they find terrifying and dangerous. This is a smart, playful, and compassionate collection worthy of repeated reads. —I.M.

Long Island, by Colm Tóibín

Bad historical fiction is weighed down by descriptions of locomotives and teacakes and tchotchkes. Colm Tóibín’s novels, by comparison, are trim and spare, his descriptions limited to what his characters are looking at. In 2009, he turned an immigration narrative we had all seen before (boats, jobs, love story) into the transportive best seller Brooklyn. Fifteen years later, he finds his heroine washed up in the suburbs and gives her a plotty excuse to return to Ireland: Her husband has conceived a baby out of wedlock, making her angry enough to leave (or think about it). Back home, a love triangle involving Ireland’s rocky beaches makes the book feel as tightly cranked as the first, though it’s somehow even sadder, especially in the exchanges between a mother and daughter who lost each other years before. —Adriane Quinlan

Atta Boy, by Cally Fiedorek

The first chapter of Cally Fiedorek’s debut novel, Atta Boy, invites readers to Liffey’s, the kind of sordid Port Authority dive where many a fledgling writer has spent a disconsolate Christmas Eve, but which rarely appears in the increasingly Brooklyn-centric canon of contemporary New York fiction. Gleaming façades notwithstanding, the scene where erstwhile bartender and failed actor Rudy Coyle finds himself upon moving to the East Side proves no less disreputable. Befriended and employed as a lackey by Jacob Cohen, a thinly veiled likeness of the longtime Trump attorney Michael Cohen, Rudy gets tangled in the fallout of a monopoly on taxi medallions that has spawned an epidemic of driver suicides. By means of hard-boiled prose and intermittent flights of Bellowian introspection, this Queens boy’s apprenticeship in the loan-shark biz erupts a nascent class consciousness amidst the flimsy opulence of Manhattan’s nouveau riche. —Andrew Marzoni

The Husbands, by Holly Gramazio

Holly Gramazio’s debut novel has a killer hook: What if you had a magic attic supplying you with an endless cycle of husbands? It’s the best kind of high-concept question, one that opens up plenty of space for a writer to play in. And Gramazio (whose background is in game design), has lots of fun exploring every corner of her husband-filled world. The protagonist, Lauren — single and loving it, until she comes home to find a husband she doesn’t remember, who keeps turning into a different spouse whenever he goes into the attic — has the unique opportunity to examine the little ways we all soften at the edges to fit the people in our lives. Lauren, it turns out, learns a lot more about herself and what she values (or doesn’t!) than she does about any individual husband. —Emily Heller

Thieving Sun, by Monica Datta

This debut novel from academic Monica Datta came out in March with little fanfare and didn’t pick up steam until an early-summer endorsement from publicist Kaitlin Phillips, who dubbed it “book of the year.” A small, experimental book structured around microtonal music scales, it follows Julienne, a sculpture student, and Gaspar, a composer, who meet in college, spend the next decade together, then drift apart. As Julienne struggles to find herself working odd jobs, Gaspar flits around the world until tragedy befalls him. It’s an intricate story that requires some effort (or in my case, a pencil), but the payoff is worth it. The writing is dazzling and mysterious, and the world Datta builds — one filled with grief, questions of origin, and the act of creation — is expansive yet so precise. I don’t know why this book isn’t getting more attention. —Lauren Ro

James, by Percival Everett

A re-imagining of a classic work of art has become a time-honored — if sometimes spotty — pursuit, and with James Percival Everett creates an original masterpiece that both complements and rivals one of the most iconic American novels, The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Written from the perspective of Huck’s loyal companion, the runaway slave Jim (James), the titular adventures of Mark Twain’s book are instead experienced here as the life-or-death trials James faces while he evades capture and strategizes a way to free his enslaved family. There are plenty of references to the earlier novel — and there’s still humor to be found despite the constant danger — but Everett grounds the narrative in James’s rich interior life and a larger historical context that brings a new depth to the familiar characters. This book will linger with you. —Tolly Wright

➽ Read James Yeh’s review of James.

Headshot, by Rita Bullwinkel

In a shabby gym in Reno, Nevada, teenage girls face off in a youth boxing tournament under a shifting ray of daylight that “fills the whole space with a dull, dusty brightness” and surrounded by a sparse crowd of mostly uninterested coaches and parents. The novel enters deep into the girls’ minds as they assess one another’s weaknesses and coax themselves through the rounds, which are described in brutal, bloody detail. Each fighter has her own source of competitive energy, but they’re all realistically ambivalent, too — unsure about why, exactly, they’re drawn to a sport that gives them so little for their trouble. Rita Bullwinkel’s debut novel is as tense and disciplined as its characters, and she has a gift for capturing the way their minds wander far from the ring and back again: One girl counts off the digits of pi, while another obsesses over a death she witnessed as a lifeguard. There’s a mesmerizing sense of limitlessness to the narrative, which roams far into the future of these fighters even as they’re absorbing hits in the ring. —E.A.

Lessons for Survival, by Emily Raboteau

Raboteau emerged on the scene some two decades ago as a writer of sharp, incisive fiction that mapped the contours of identity and race. In recent years, she has become a literary voice of consciousness about the ongoing climate crisis. Across a series of essays, book reviews, and conversations, Raboteau has charted the progression of the crisis, our shared culpability, and our responsibility to develop practical solutions. Lessons for Survival is, in many ways, a culmination and continuation of this work. Raboteau travels locally and abroad to capture stories about the impact of the environmental crisis, and the resilience of communities that find themselves on the front lines. She also writes authentically — her prose seamlessly melds slang and heightened language — about her own experiences as a Black mother, whose identity has shaped her understanding of these issues. This is scintillating work, an essential primer for our times. —Tope Folarin

The grand irony of this juncture in history is that at the very moment when the problems we’re facing — climate change, economic inequality, cross-border violence — require global solutions, our societies have become more atomized than ever. This is the case both within various societies, in which individual concerns increasingly trump collective interests, and between societies, whereby individual countries pursue their objectives at the expense of global cooperation. In their new book, Solidarity: The Past, Present and Future of a World-Changing Idea, Leah Hunt-Hendrix and Astra Taylor offer an essential antidote: a renewed commitment to solidarity. Their book is ambitious and comprehensive. It traces the evolving meaning of solidarity from ancient Rome through the Black Lives Matter movement and identifies different kinds of solidarity, how they arise, and how effective they are in forming and maintaining social bonds. They persuasively argue that in order to create a more “egalitarian world,” we must learn to cultivate and practice the kind of solidarity that “chang[es] the social order toward one that is both freer and more just.” —T.F.

Help Wanted, by Adelle Waldman

Set at a big-box store in upstate New York, Help Wanted recalls Mike White’s Enlightened in its textured portrayal of how small humiliations and injustices at work inevitably boil over into righteous rage. It’s a novel that lingers in the imagination, by which I mean, after you read it you’ll think of it every time you shop at Target, forever. —Emily Gould

➼ Read Emily Gould’s interview with Help Wanted author Adelle Waldman on the Cut.

Stranger, by Emily Hunt

Emily Hunt’s second book of poems considers real intimacy mediated by apps. In “Company,” a long poem originally published as a chapbook, the speaker works for a flower delivery startup, gently pulling roots from soil, culling, clipping, and handing off arrangements. These moments are sensorily rich, slotted into 15-minute assembly-line shifts, and short lines. In “Emily,” Hunt uses messages from Tinder as her source material, not to mock (or not only to mock) the senders or the stilted situation of meeting online, but to construct a self in relief, as seen and spoken to by strangers. A funny and surprising interaction with dailiness, including our phones — the hardware and the relationships maintained through them — and whatever else is still tactile. —M.C.

Dead Weight: Essays on Hunger and Harm, by Emmeline Clein

Emmeline Clein’s Dead Weight seems destined to fundamentally reshape how we think and write about the subject of eating disorders. What separates Clein’s book from others on the topic is her commitment to treating the sufferers of eating disorders with the kind of dignity that clinicians tend to withhold. She writes as an insider, telling both her personal story and sharing the stories of her “sisters,” which range from Tumblr accounts to clinical studies co-authored by their subjects. Throughout, she refrains from including the graphic details that have historically plagued books about the subject. “Too many people I love have misread a memoir as a manual,” she writes. The book she writes instead confronts the complicated entanglement between eating disorders, race, capitalism, and the ongoing erosion of social safety nets. Stereotypes about eating disorders commonly portray the illness as one rooted in control. Dead Weight not only exposes how little control patients have had over their own narratives and bodies, it returns the narrative to those who have suffered from the disease. This is a moving, brilliant, and important book. —I.M.

Wandering Stars, by Tommy Orange

Orange’s Pulitzer-finalist debut, 2018’s There There, is a tightly constructed, polyphonic book that ends with a gunshot at a powwow. His follow-up, which shares the first one’s perspective-hopping structure (and several of its characters), is a different beast, an introspective novel about addiction and adolescence. The story begins in the 1860s, when a young Cheyenne man becomes an early subject in the U.S. government’s attempts to assimilate Native Americans. The consequences of this flurry of violence and imprisonment will reverberate through generations of his family, eventually landing in present-day Oakland, California, where three young brothers live with their grandmother and her sister. The oldest brother, Orvil, was shot at There There’s powwow, and even though he survived, the heaviness of that day is weighing on him and his family. Prescribed opioids for the pain, he finds that — like several of his ancestors, though he has no way of knowing that — he likes the sense of removal they give him. Orange’s novel is unusually curious and gentle in its treatment of addiction; he lets his characters puzzle out why they’re drawn to intoxication, managing to balance a lack of judgment with an understanding of the danger they’re in. —E.A.

➽ Read Emma Alpern’s full review of Wandering Stars.

Come and Get It, by Kiley Reid

In Come and Get It, the second novel from the breakout author of Such a Fun Age, the University of Arkansas serves as the backdrop for Kylie Reid’s assessment of race, class, and social hierarchy on a college campus. Over the course of a semester that shifts between the perspectives of Millie, a meek yet dutiful R.A., Kennedy, a shy transfer student with a traumatic secret, and Agatha, a visiting professor out of her depths, the primary characters are forced to grapple with the heady concepts of desire, privilege, and the rules of social conduct in an environment where the the game is rigged and fairness is reserved for a select few. Light on plot and heavy on character development and social commentary, Come and Get It is the kind of book you put down and immediately want to discuss. But fair warning: If you ever lived in a college dorm in the U.S., this book might inflict a non-negligible amount of PTSD. —A.P.

The Rebel’s Clinic, by Adam Shatz

In these chaotic times, Franz Fanon’s work is constantly and enthusiastically referenced. A new generation of activists — as many before them — has repurposed Fanon’s words to describe our current travails, and to propose how we might move forward. Fanon persists in the activist imagination as a kind of radical soothsayer, an intellectual who can speak authoritatively about our moment because of his identity as a Black man and colonial subject who personally experienced the barbarity of a colonizing power. In The Rebel’s Clinic, Adam Shatz complicates our understanding of Fanon’s life and work, and persuasively conjures the human being who wrote the words that have inspired so many. Among Shatz’s most important interventions is to highlight Fanon’s vocation as a doctor who “treated the torturers by day and the tortured at night.” Shatz’s book is a chronicle of a man who, because of his identity and gifts, was obliged to constantly reconcile opposing ideas and ways of being. —T.F.

I Survived Capitalism and All I Got Was This Lousy T-Shirt, by Madeline Pendleton

Finally, a book about money that knows money is evil. TikTok’s favorite Marxist small-business owner wrote a book on financial literacy, and it delivers on its promise. Half memoir, half how-to, the book explores Pendleton’s journey to fiscal solvency while also including handy tutorials on things like buying a car and enduring financial stress. (Pendleton starts the book with the death by suicide of her partner, primarily motivated by looming bankruptcy, so that how-to hits especially hard.) Pendleton’s personal story brings pathos and relatability to her finance guidance. Every hardship someone of her generation could fall prey to, she does — predatory loans, for-profit college, go-nowhere internships, not realizing couch-surfing is the same as homelessness and therefore taking longer to embrace class solidarity. But for every setback, she notes a resource for resilience. Everything from the kindness of the punk scene to good grifts to pull on the phone company, this book gives you the tools to create a sustainable life in late capitalism. —Bethy Squires