Gaspar Noé’s Love is what one might call a “penis-forward” movie. Its opening shot, set to the mournful strains of Erik Satie’s “Gnossienne No. 3,” is a fixed-frame view from the foot of a bed of a young man whose erection is being stroked by a lithe brunette, her dark nipples and ’70s pubic triangle facing toward the camera while he rubs her clitoris. We watch for three full minutes, our eyes trained on the couple’s facial contortions and involuntary muscle spasms as they give and receive, the rhythmic touching of flesh the only sound other than the swells of the orchestra, until he ejaculates and she licks him clean. This, by the way, all happens in 3-D.

“It’s not shocking, come on! It’s a sweet double hand job,” says Noé, on a cold September morning in Toronto, when I ask him if audiences will be taken aback by his movie’s opening cum shot (out of a total of three). This is, after all, a kind of unicorn: a widely distributed full-frontal three-dimensional movie, complete with a very long, very graphic threesome and a trip to a Parisian swingers’ club in which the extras were French porn stars and some of the movie’s crew members who felt like stripping down. European film’s most Dionysian provocateur, Noé is often mentioned in the same breath as director Lars von Trier, but where the latter approaches carnality with an existential chilliness, Noé’s work is brimming with a glutton’s appetite for libidinal indulgence that suggests he actually likes sex — an appetite that he matches with an exhilarating cinematic ambition. The kind of ambition needed to make a beautifully shot, technologically advanced, emotionally wrenching, high-art skin flick.

On the day we meet, Noé has just flown in from Paris for Love’s North American premiere at the Toronto Film Festival and looks like it, in a rumpled black T-shirt and black jeans, with rampant stubble and a black horseshoe mustache that contrasts with his bald pate and genial air. We’re still talking about the film’s opening scene, because how can you not? “When it’s raining outside, you just want to stay in bed and have sex,” he continues. “I tried to put what I consider the sweetest things in life [in the film]. Why would you always portray your fears but not also your pleasures?”

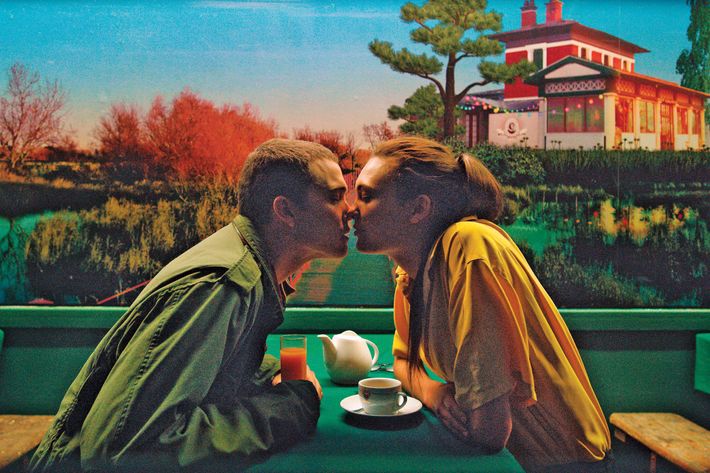

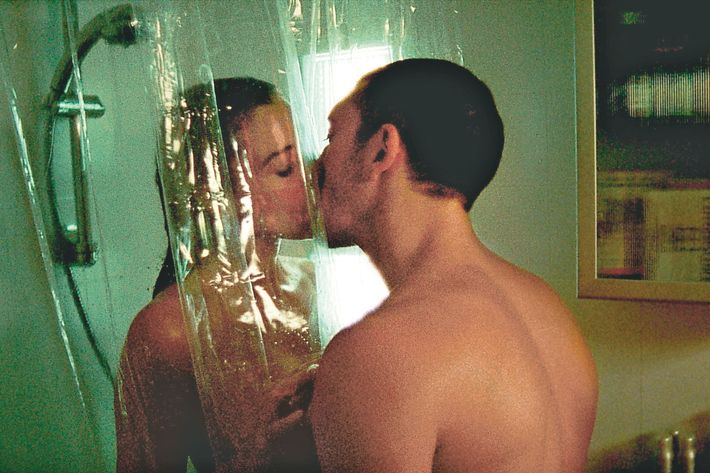

Fear and pleasure have long been a specialty of the Argentina-born director, whose critically divisive yet very memorable movies have hinged on such extreme subjects as incest (1998’s I Stand Alone), rape (2002’s Irreversible), and hallucinogenic out-of-body experiences (2009’s Enter the Void). The move to 3-D is just Noé’s latest experiment in visceral immersion, an extension of a sensibility that’s employed swirling cameras and strobe lights to convey the experience of tripping on DMT while flying over Tokyo at night and placed us at eye level with a man whose skull is getting bashed into something resembling regurgitated beef. Noé tells me that with Love, he wanted to channel his trademark cinematic hyper-intensity into a realistic portrayal of the emotional and erotic experiences of people in their 20s, an age ruled by self-discovery and inhibition. Using a nonlinear structure, improvised dialogue, and mostly nonprofessional actors, the movie shows the rise and collapse of a passionate relationship — between Murphy (Karl Glusman), an American film student living in Paris, and his painter girlfriend, Electra (Aomi Muyock) — that can’t withstand a surfeit of drugs and sexual partners.

Noé, as you’ve by now inferred, is not a bashful conversationalist. He tells me that as a teenager he’d masturbate two to three times a day to Penthouse magazine and ’70s soft-core (recorded on VHS, no less). Much of the inspiration for Love came from his believing we need more of the kinds of visuals that turned him on as a horny young man. “There’s nothing like erotic cinema anymore,” says Noé, “so if you want to see sexual images, you end up Googling these gang-bang images with the guys who look like firemen and shaven girls who look like bodybuilders — and that has nothing to do with what these teenagers are going to experience. So maybe it’s better to clean their eyes with images that are closer to life.” Plus, unlike your traditional films that show full-frontal and ejaculation, two-thirds of Love is expository, and every scene but the first is imbued with loss. “The movie is mostly arousing on a sentimental level,” says Noé, who follows that sweet double hand job with a flash-forward in which we learn that the girl has fallen into a depressive, drug-abusing state owing to the guy’s infidelity and has gone missing. “I cried during editing,” he says, “it was so sad.”

Noé’s longtime producer Vincent Maraval marked the occasion of Love’s world premiere at the Cannes Film Festival in May by tweeting out a flyer for the movie featuring a single breast and a penis spouting semen with the caption “Love à Cannes, Champagne!” (He’d borrowed the joke from Noé.) Both Irreversible and Enter the Void had previously shown at Cannes in the prestigious competition for the Palme d’Or; this time, the festival made Love an official out-of-competition selection, to be screened, as seemed fitting, after midnight — still quite an honor. The festival’s typically hierarchical admission methods had been ditched for frenzied first-come-first-served seating. I’ve never seen a Cannes screening so charged at curtains-up, and the audience’s energy rarely abated, from some very pointed walkouts to an extended standing ovation led by Noé’s friend Benicio Del Toro. After the screening, Glusman told me that he ran into the Spanish actress Rossy de Palma, a muse of Pedro Almodóvar, in an elevator. “As soon as she recognized me,” he recalled, “she said, ‘Ah, your dick! Is it your dick?!’ ” (It is, in fact, his dick.)

Love has actually been 17 years in the making. Noé wrote the seven-page story treatment while shooting his first feature, I Stand Alone, and presented it to the French actor Vincent Cassel after the two met in a nightclub. Noé originally thought that only a real couple or an ex-couple could deliver the intimacy the project needed. Cassel, likewise, thought the film might be a good one for him to do with his real-life partner at the time, Monica Bellucci. “But when they read the script,” says Noé, “and saw all the love and sex scenes that it involved, they said no.” (Instead, they starred in the deeply disturbing Irreversible, in which Bellucci’s character is violently assaulted.) The idea to shoot Love in 3-D, though, came to Noé just two years ago, while visiting his dying mother in Buenos Aires. “She was the brightest woman I met,” he says, “but at the end her brain fell into pieces.” He wanted to have something of her to hold on to, so he began filming her with a handheld 3-D camera that he’d recently bought. “Then, when I was watching those images, I saw that they were more realistic and more touching than 2-D images because of the depth of the screen. And I thought, Well, maybe if I do the movie in 3-D, it’s going to become more emotional.” Also, he adds, “by putting on glasses to watch a movie, you create a tunnel effect. You are less aware of who’s sitting next to you.”

Noé calls Love “my first first-degree movie,” meaning it’s “the closest thing I know to life, and the most personal.” This, he explains, is in opposition to second-degree movies, which are about other people, or third-degree movies, which are movies about other movies. (Quentin Tarantino, Noé offers, is a third-degree filmmaker.) Of all the outré situations depicted in Love, Noé says there are only two he hasn’t experienced himself: The first is accidentally getting a girl pregnant, “but it happened to many of my friends, so I relate, or maybe I had that fear my whole life and you can see it onscreen.” The second is having a girl cajole him into having sex with a transsexual while she watched, which turns out to be one of the movie’s more comical scenes. Noé also appears in the film as Electra’s gallerist ex-boyfriend, and for those of you who make it to the point where he pulls an erect penis out of his pants, yes, that is his organ. The director previously made a (flaccid) penile cameo in Irreversible, in a scene set in a gay sex club. Why? Why twice? “I don’t know,” he says. “When you make a movie, it’s like playing a game. It’s kind of funny to show your dick to everybody in the country.” Now 51, Noé has a partner, filmmaker Lucile Hadzihalilovic, and says he isn’t a swinger and is agnostic about free love, but “I party a lot, and I was a party monster.” While we discuss his feelings on monogamy, he also mentions something called “occasion felon” that happens to artists on the road, where “temptation makes the thief. You’re not naturally a robber or a thief, but it’s the situation that sometimes makes it easy to steal.”

To find Love’s actors, Noé used what he terms “savage” casting (casting sauvage, in French) — which amounts to meeting people at bars or on the street, having a drink with them, and filming them on an iPhone to see if they’d pop. He also places a heavy importance on feeling interpersonally simpatico with his actors. “You should do a movie with people that you would enjoy taking a holiday with.” Once he’d narrowed his list of potential actors, he began playing matchmaker. “That’s why it took a long time to do the casting,” he says, “because sometimes you would meet the guys, but for one reason or another they were repulsive to some girls, or vice versa.” Muyock is a Swiss model Noé met at a party; the other female lead, Klara Kristin, who plays a teenage neighbor whom the protagonist couple invites into their bed, is a Danish painter’s assistant he saw dancing at a nightclub. Glusman, who has since landed roles in upcoming movies by Tom Ford and Nicolas Winding Refn, was an unknown New York theater actor recommended by a friend. Noé Skyped with him and liked him, though the audition didn’t involve disrobing. He says, “I knew a girl who had seen him naked and I asked her, ‘How is he?’ And she said, ‘He has everything you need.’ ”

The first time Glusman and Muyock kissed was the first day on the Love set, a day that began with a close-up of Glusman’s genitals. “Maybe the hardest thing for Karl was on the day I said, ‘Can we do this cum shot on the camera?’ ” says Noé. “I barely knew him. He said, ‘Can you please move? Because I lose concentration.’ He was staring at me, and the guy with the mustache behind the camera was maybe not the best way to concentrate on what he was thinking of. But, yeah, he came on the camera.”

The director and the star are still close, and Glusman accompanied Noé to Toronto. They made a funny pair, this short French-Argentine and his towering, Oregon-raised sidekick. The last I saw of them was at a party at a Toronto pub chain called Gabby’s that their publicists had brought them to after the premiere. It was one of those decidedly un-starry, late-in-the-festival casual affairs beloved by media folks and attended by zero famous people. Glusman awkwardly mingled with the crowd. Noé ordered shots for everyone and at 2 a.m. could be found loudly singing the Clash’s “Rock the Casbah” at the karaoke machine up front — though he substituted in the words “Run Gaspar.” Watching him, I was reminded of something he’d said earlier that day about how much joy he derives from people storming out of his movies: “It’s like a magician who pulls a rabbit from his hat. He’s happy, but if you pull a dragon from your hat and people scream and run away, you’re even happier.”

*This article appears in the October 19, 2015 issue of New York Magazine.

*This article has been corrected to show that Lucile Hadzihalilovic is Noé’s partner, not his wife.