While World War II raged overseas, pop-culture creators on the American home front were in an awkward spot: How could their art help the war effort without becoming dry and preachy? How could they adapt light entertainment to document the anxieties and deprivations of life during wartime? Nowhere was this artistic crisis felt more than in the still-young (and insanely popular) mediums of cartooning and comic strips. Warren Bernard’s gorgeous new collection of rare drawings from the war years, Cartoons for Victory, dives into that strange period.

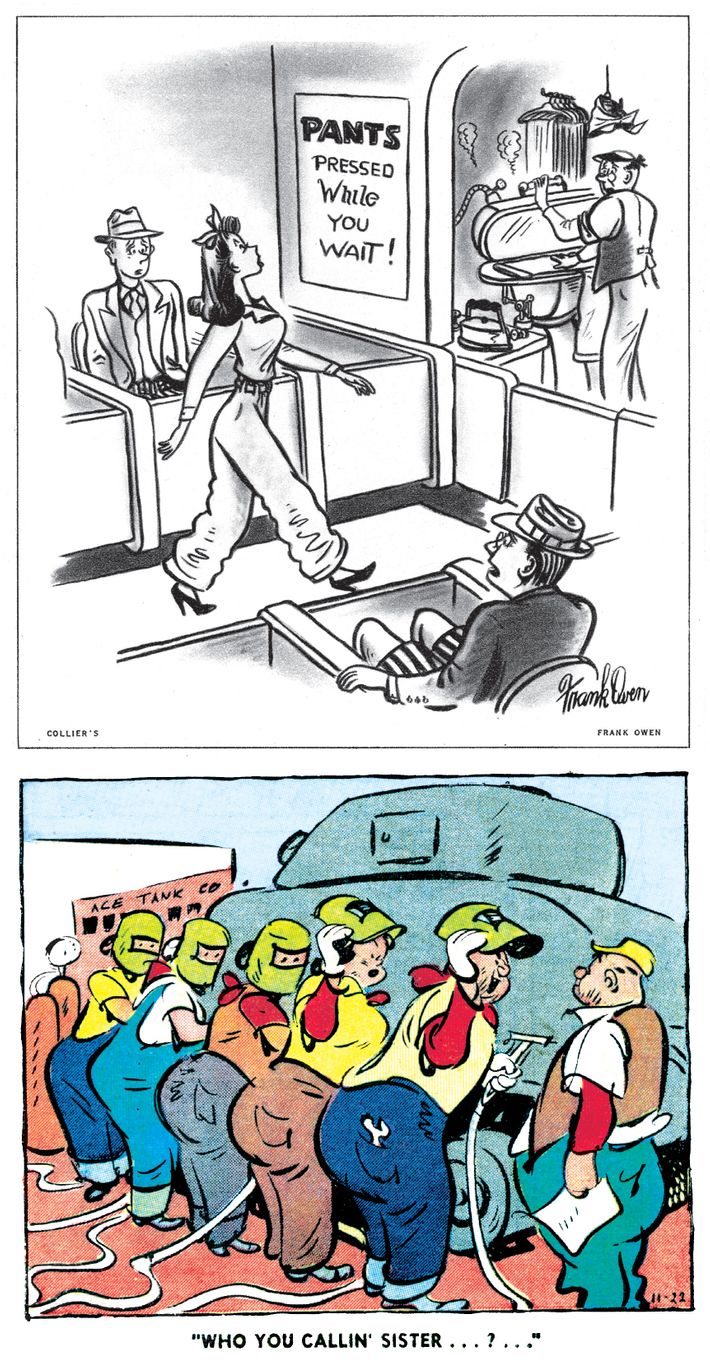

The collection features single-panel editorial cartoons as well as comic strips and advertisements, boasting a high percentage of previously unseen material. There’s wartime work by cartoonists such as Charles Addams (The Addams Family), Harold Gray (Little Orphan Annie), Harvey Kurtzman (Mad magazine), Will Eisner (The Spirit, A Contract with God), as well as many less-known artists of the period. More than 90 percent of the cartoons and comics in this book have not been seen since their first publication. Bernard gathered them over years of unstinting research through private collections and the obscure holdings of public sources.

The shock of witnessing characters like Batman and Donald Duck talking about the 20th century’s largest war is akin to discovering a photo of your grandmother in an embarrassing outfit, taken decades before you were born. This tension between recognition and knowledge, of familiarity with these characters and the stark difference of context in which they lived back then, exposes an integral facet of the war: It politicized everyone and everything, even Mickey Mouse.

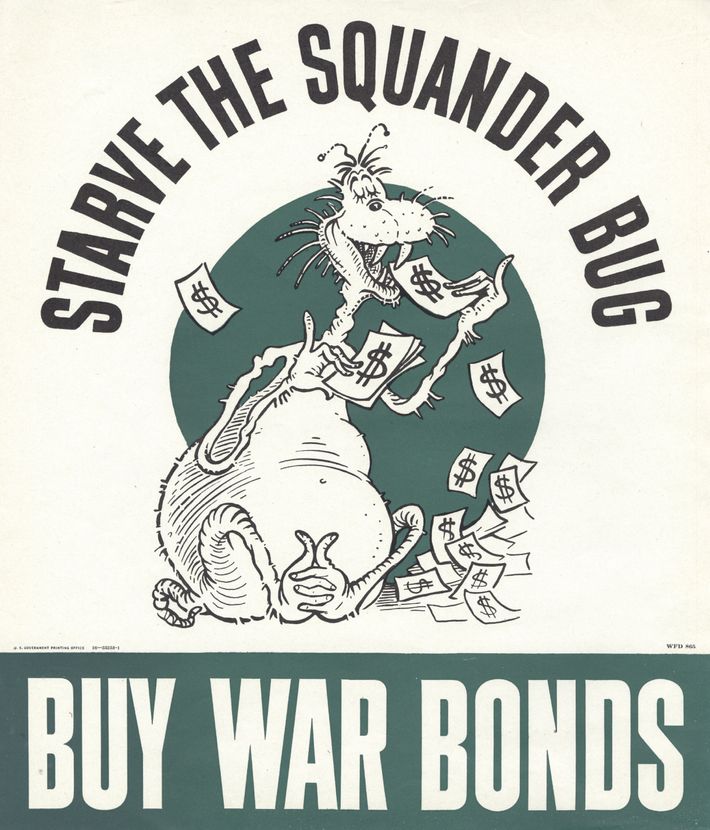

And yet, cartooning was, in many ways, the ideal medium for talking about the war. As a mass medium, it was an efficient and simple way to communicate messages — both propagandistic and otherwise — about wartime hardships. And the laws of physics don’t apply in the world of cartoons. These are worlds where extraordinary and unexpected things are possible. While they offer us escape and transcendence, they also provide a darker dimension, facilitating distorted perceptions that mimic the language of reality but conceal the graphic truth of our times. We caught up with Bernard to talk about collusion between cartoonists and censors, the shameful blot of cartoon racism, and exploding the “Greatest Generation” myth.

How did the war politicize the world of cartoons?

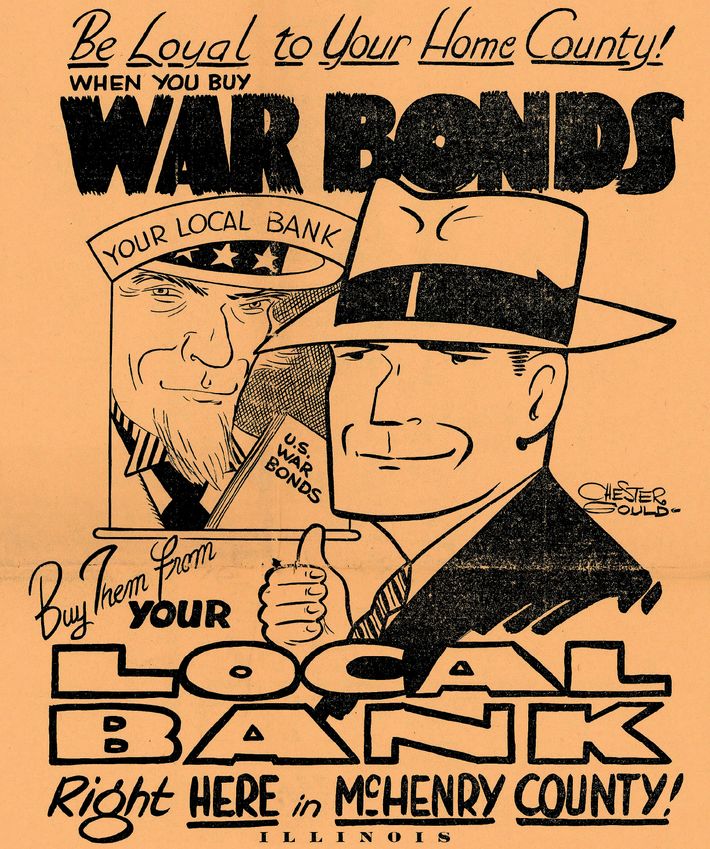

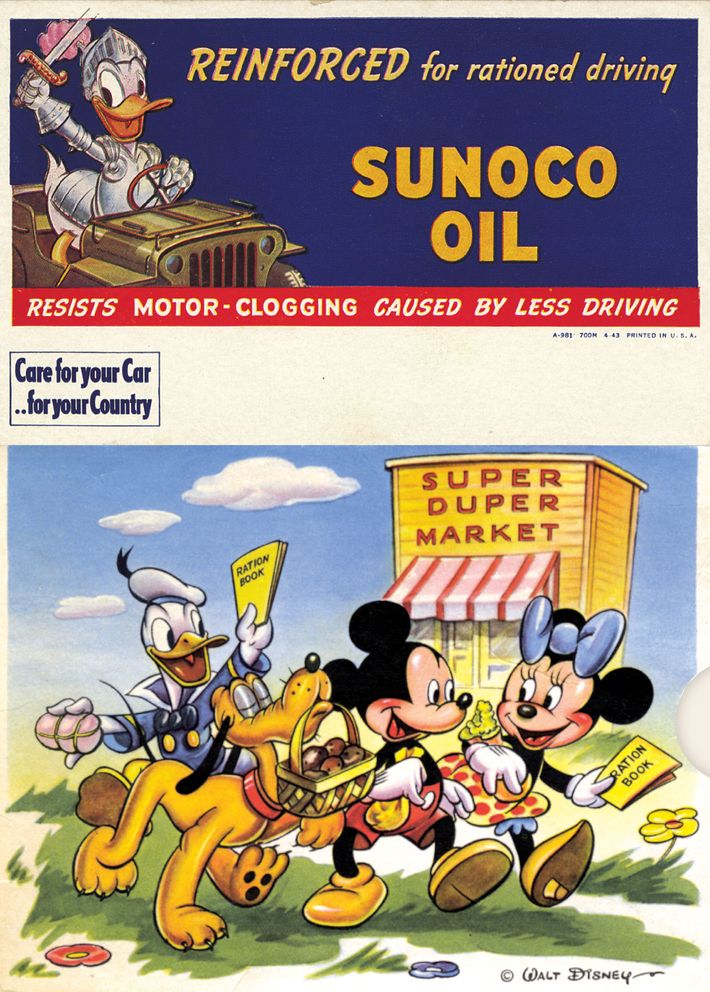

Walt Disney turned his studio into a propaganda arm of the government, making a number of cartoon training films for the armed forces as well as propaganda films for the public which used Donald Duck, Mickey Mouse, Goofy, and other Disney characters. Entertainment suddenly had a political purpose to it. By October 1940, Ham Fisher’s Joe Palooka had joined the Army as a recruit. 1941 saw further comic strips and comic-book characters deal with war themes, all of them either promoting preparedness or advocating intervention (a minority view at the time), culminating in the introduction of Captain America in early 1941 and in late 1941 Superman, also fighting the Nazis.

As the war raged on, the cartoon industry solidified, and the armed forces became the incubating ground for some amazing talent. The newspaper Stars and Stripes was a training ground for Dick Wingert, whose Hubert cartoon found itself carried in newspapers around the United States after the war. Future Superman artist Curt Swan found some of his early spot illustrations in Stars and Stripes, as did future Pulitzer Prize–winning editorial cartoonist John Fischetti. Over in the Navy, ex-Disney animator Hank Ketcham found himself drawing cartoons and illustrations that were syndicated out to dozens of Navy-base newspapers to help sell war bonds to Navy personnel. This was a strange moment in history where the “lowly” art form of cartoons intersected with a horribly important war. I wanted to see how the two things affected each other.

A lot of the cartoons that made it into the book came out of your personal collection. What got you interested in collecting WWII cartoons, and what do they mean to you?

Well, growing up as a kid in the ‘50s and ‘60s, it was difficult to escape the whole WWII thing. There was a lot of stuff on the TV at that time, there was combat, there was the absurdity of Hogan’s Heroes. There was a certain glory about it. American society during the Second World War was very different to what it is today, and there were opportunities for cartoonists that you don’t have today. The Saturday Evening Post had a circulation in the millions. So the role of pop culture from the American-society perspective got me interested. If you think of cartooning, it really lasted [as a dominant medium] for 15 years before TV started taking over. When you put all this together, there were these four years when a huge change in society occurred on top of this amazing outlet of cartoons. That’s what led me down this road.

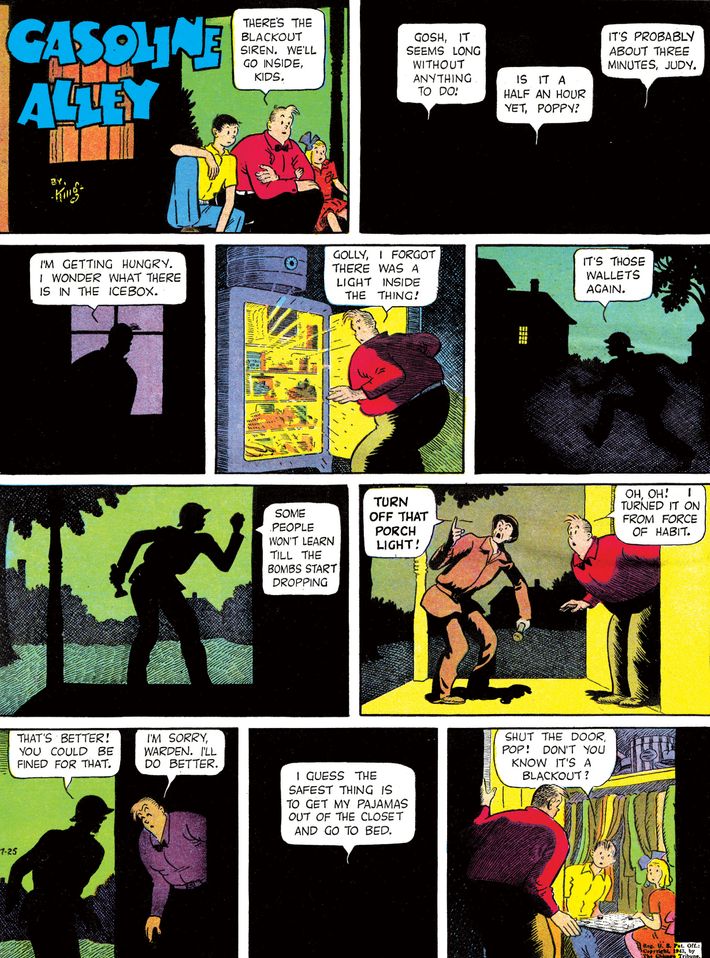

Why was the medium of comics regularly employed as a tool of instruction and propaganda?

There were a couple of reasons. One was the outright popularity of it. Secondly, the Army and the Navy had a problem with illiteracy. They had a lot of people who couldn’t read or hadn’t gone past eighth grade. You can’t give complex manuals to people who can only read up until an eighth-grade level. Plus, they believed they could teach people better by combining images and words. If you read something that says, “Don’t put your finger behind the trigger of a gun,” and you see someone trying to do it, that adds a level of reinforcement.

Was there an entertainment value to these cartoons?

Cartoons served many purposes. They were there to get people to laugh about rationing and blackouts and other deadly serious things. It’s hard for us to imagine walking into a Home Depot and not seeing any household items for sale, or walking into Whole Foods and seeing an empty meat counter. Some people had mandatory six-day working weeks. And then there was this huge thing hanging up there, 3,000 miles away, and that thing was disrupting every single part of your life. There is a certain amount of stress you have under those circumstances. In times like that, you hope cartoonists will come along and make things a little bit easy.

Did you encounter a dark side of this medium in terms of racist propaganda or ugly jingoism?

That’s one of the reasons I made the last chapters about the internment of Japanese-Americans and Jim Crow. There is this image we’ve got of WWII that’s like a typical Hollywood film where everyone pulled together, everyone rationed willingly, but guess what? Bad stuff happened. There were also crude depictions of Germans and Japanese. Less so of Italians. And it’s not a justification, but the Germans and the Japanese did the same to us. If you look at the German iconography, Roosevelt was a Jewish swindler who wanted to take over the British Empire.

What kinds of contradictions did you find between how Americans of the time perceived themselves and how they actually were?

One of the books that I found from that time was a cartoon from the creators of the Blondie strip with an A-B-C about war. It had a page that said “T is for Tolerance.” Well, we weren’t tolerant towards the Japanese-Americans, we weren’t tolerant of our Germans, we certainly weren’t tolerant of African-Americans. I was very happy to find the cartoons I included in the last chapters that were anti-racist. I found a cartoon from January 1945 in which Japanese-Americans and African-Americans are handing Uncle Sam the Constitution in a pair of glasses, asking him not to forget what we fought for. That was the perfect exclamation point for the book.

In terms of how people viewed themselves and how the battle was going on, there was a purity to it that you see in these cartoons that I think people embraced. If I hadn’t put in the chapters about Japanese-Americans and African-Americans, you would come out feeling pretty good about the selflessness with which American went and fought the war, and that was the basis of Tom Brokaw’s The Greatest Generation. There’s no question that the cartoons that came out of [the war] added to that mythology, and if I had not tailored things, you would get a different impression. So I tried to provide that counterbalance to the “we are the arsenal of democracy” mythos. There were sacrifices on the war front and sacrifices at the home front, but it wasn’t that clean. And I think there is an appropriate cynicism about that now that didn’t exist back then.

How did cartoonists get along with wartime censors? A lot of these creators, especially people like Harvey Kurtzman, went on to have extremely subversive careers after the war.

I found during my research that there was collusion between the government and the cartoon community, which dictated that certain things were to be represented properly. The environment around this war was unique because the level of subversion one would have expected from these cartoons didn’t materialize. The state knew where the media outlets were and how to get into them and use them in really sophisticated ways for their own purposes. Rather than subversion, the opposite was true. The concept of patriotism was really different from what it is today. There had been an isolationist movement in the United States, but the second Pearl Harbor was attacked, it evaporated in a heartbeat.

What would you like the reader to take away from this book?

People today are not impacted by the wars we fight, unless there is some relative or friend in the armed forces. We no longer have our skin in the game. Back then, every American had to make a sacrifice, every American had to get involved. I want people to reflect on that. I also want people to know that the media can collude. During World War II, independent media became an arm of the United States government, whether this was done implicitly or explicitly. Lastly, the war was not as clean as people would like it to be. After the war, Americans forgot and glossed over the uncomfortable truths. [Air Force general] Curtis LeMay said that if we had lost the war, he would have been tried as a war criminal. We must remember that.