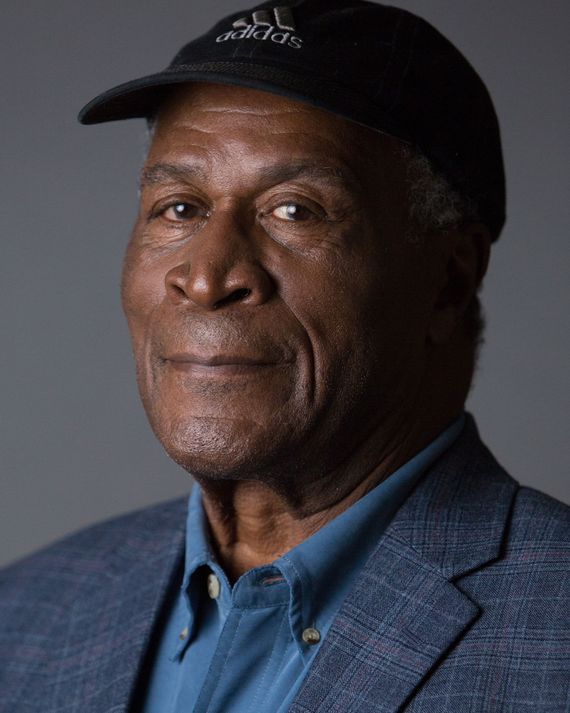

This interview with John Amos was originally published in 2015. We’re republishing it now with an expanded intro following the actor’s death at 84.

John Amos was one of those actors fortunate enough to have more than one iconic role on his résumé. His two biggest parts were as patriarch James Evans Sr. on Good Times and the elder Kunta Kinte on epic miniseries Roots. But even his smaller roles endured — Cleo McDowell in the two Coming to America movies, Admiral Fitzwallace on The West Wing, or the one that first brought him fame: Gordy the weatherman on CBS’s The Mary Tyler Moore Show. Amos appeared roughly a dozen times over the course of that show’s first three seasons, and even though he left in 1974 for the regular gig on Good Times, his character was vital enough that he returned with his own spotlight episode during Mary Tyler Moore’s final season.

Amos, a New Jersey native, died of natural causes on August 21 in Los Angeles at the age of 84, though his passing wasn’t officially announced by his publicist until today. While family drama related to his children and their squabbling resulted in a slew of unfortunate headlines last year, that messiness took nothing away from Amos’s status as an icon of 1970s television and one of the most beloved small-screen dads in the history of the medium. It was not a conventional path to stardom: He was nearly 30 years old when he got his first big Hollywood job in 1969, landing a gig as a writer on a variety show starring future Roots castmate Leslie Uggams. He’d spent much of the previous decade trying to make it as a professional football player — including a brief stint training with the Kansas City Chiefs. During his time in Kansas, Amos started doing some writing, and the response from his teammates and coach Hank Stram to a poem he’d penned gave him the confidence to make a career change. “Stram said, ‘I don’t know if you’re going to make it in football, but I got a feeling you’ve got another calling,’” Amos recalled in a 2014 interview with the Archive of American Television. And while writing didn’t end up working out either, it opened the door to decades of success as an actor.

In 2015, Vulture caught up with Amos by phone to dive deeper into his Hollywood career — like his work on The Mary Tyler Moore Show and the time the show’s producers had to retaliate against a racist crew member. He talked to us about his bumpy ride on Good Times, working with co-stars Esther Rolle and Jimmie Walker, and how he ultimately patched things up with producer Norman Lear after a very public falling out. Throughout the conversation, Amos made it clear that for him, his time in front of the camera was never just about a paycheck or achieving celebrity, particularly during his run on Good Times. “I was carrying the weight of being the first Black father of a complete family, and I carried that responsibility seriously,” he said. “I was not going to portray something that was less than redeeming.”

I want to talk to you first about The Mary Tyler Moore Show, since you’re part of this new PBS tribute to Ms. Moore. Your role on MTM was sort of your first big national exposure as an actor, though you’d worked as a writer for Leslie Uggams’s CBS variety show back in 1969. I read an interview with you where you talked about how you had wanted to break into performing on her show, but the producers said you couldn’t do both. Why was that?

Back then you were lucky to be in the business in any working capacity. The idea that I would be in there as a writer, and then want to perform, too? That was just an abstract concept to the producers at that time. They weren’t ready for somebody who thought they could act and write. I had to wait until my turn came.

When you say they weren’t ready, was it because you were young, or because you were African-American?

I think it was a bit of both. I was just getting started, and that was my first network writing job. Although I had written comedy and performed on a local television show, Lohman & Barkley, which won an Emmy. In fact, we all wrote and performed, the “we” being the entire writing staff, which consisted of Craig T. Nelson, Barry Levinson, the late McLean Stevenson, amongst others. We were all just getting started, and that was wonderful training for us. Having written and performed on a local show that did successfully, I had every reason to believe I could do that at the network level. But they said, “No, you can only do one.”

So how did you ultimately make the jump to performing, and to MTM?

One day I had lunch with two of the writers on the Uggams show, Lorenzo Music and Dave Davis. And they said, “John, when you act out these sketches for our guest artists, we think you’ve got the chops. We’re involved in the development of something called The Mary Tyler Moore Show, and we think you’d be right for one of the characters.” I just took it with a grain of salt. It sounded too good to be true. But later they stayed true to their word. When The Mary Tyler Moore Show was picked up to series, they called me.

Did you have to try out for the gig?

I auditioned for Mary, Grant Tinker, and the powers that be, and got the job as Gordy the weatherman. It became a recurring character.

Because of The Dick Van Dyke Show, Ms. Moore was already a TV icon of sorts even before she got her own series. What was your experience working with her?

The joy of working with Mary was, you knew who the star of the show was. It was The Mary Tyler Moore Show. So there were no attempts to upstage her, or any of the other things that usually go with actors surrounding the star. It was a harmonious set. She and Phyllis and Valerie got along great, because all they would talk about, all day long, was diets and health food. [Laughs.] As soon as they got to the set, the conversation would start. So they had a nice little group going. And they all got along great. It was a wonderful atmosphere. I felt, for the first time, that I was part of a real, meaningful ensemble. I had no idea the show was quite as successful as it was, and as it became, until later. But I was gratified to have been involved.

For someone looking to break into TV acting, it had to have been an amazing opportunity.

I couldn’t have had better training. The ensemble cast speaks for itself. Everybody was stage-trained and extremely competent, and they all spun off into their own shows successfully.

Any other memories of the cast stand out?

Ted Knight was an absolute comedic genius. And he loved his part so much. He’d fashioned him after George Putnam, who was a very right-wing news personality at that time. And he did a magnificent job — so much so that … one day he shared with the cast a fan letter he had gotten from a lady who just could not stand Ted Baxter. She said, “Ted, you are the most obnoxious, most egotistical news person I’ve ever seen in my life.” She thought that he was real. He couldn’t wait to share it with us. This woman had bought into his character 100 percent, and he loved that.

How did the role of Gordy go from a one-off to recurring?

After my first episode as a guest character, the co-creator Allan Burns came over and said, “You did well. We’ll see you soon.” No commitments, no promises. But then one day he came over and gave me a compliment. It was after one episode where I’d had a little more dialogue than usual, and I’d handled it fairly well. And he said, “This guy’s a starker.” And I said, “A starker? What the hell does that mean?” I thought I’d been called everything in the books. But the bottom line was, it was a compliment that meant you were a very competent craftsman at comedy or whatever was presented to you. I had to get that explained to me by Gavin MacLeod, or it might have been Ed Asner. I saw it as a badge of honor. I was being accepted.

What was sort of great about Gordy is that he was a weatherman — and not a sportscaster. Back in the early 1970s, that was definitely playing against stereotype.

That was indicative of Jim Brooks’s and Allan Burns’s sensitivity. They did not pander to the lowest common denominator in terms of stereotypes or cheap humor. In fact, they were so skilled as writers, they had Cloris Leachman — her character Phyllis — assume I was a sportscaster, because I was a fairly large guy and I was Black. And those were the only faces you saw in any prominence on the TV screen in those days. So they played against that. They had her make that assumption, when in fact Gordie was a meteorologist, which blew Phyllis’s mind. But I loved it! It was going against the grain, and it showed their sensitivity. They capitalized on the stereotypical thinking.

I understand not every single person on the set had such advanced thinking — that one time someone on the crew made some pretty ugly comments toward you as a “joke.”

It was so infrequent that happened. The producers created an atmosphere of tolerance so that if someone said something like that, they stood out like a sore thumb. One particular day, we were rehearsing a scene, and they wanted the photographer to shoot some good stills. And this one, let’s call him an “unenlightened individual,” said, “John, smile so we can see your teeth and we can know where you are.” There was complete silence on the set. I didn’t say a word or react at all. I knew that was coming out of left field from someone who was a little bit deranged, so no sense in me reacting. The next day that person was gone, never to be seen again. And he had been with the show since its inception. But his views on race got out of hand, and his mouth took control, and it cost him his job. They weren’t going to have anything that was going to be a disruptive factor on their set.

How many episodes did you end up ultimately doing?

All told? I’d say I did maybe ten, 12 episodes over the course of the show. It might have been as high as 14. I can’t recall. I just remember it was a wonderful experience — terrific. I couldn’t wait to get to work every time they called me. I was living fairly close by, in Topanga Canyon, and I was just starting my family, so it couldn’t have come at a better time. And I really regretted leaving the show — I didn’t realize how much I’d regret it — for Good Times, because Good Times was originally only a pilot. And nobody knew if it was going to fly. I had to make a commitment; I couldn’t do both shows. So I opted to take the Good Times offer and contract. It meant more money, but the working conditions were not as … I wasn’t as happy. I’ll leave that way.

When you got the offer for Good Times, did MTM and Mr. Tinker counteroffer a spinoff, or maybe discuss making you a series regular?

I was happy with being a recurring character. And I knew they had so much talent on the show, they had to spread it around. I was never offered the role as a regular. I’m sure that had I not gone on to the Good Times series, that was probably a discussion that might take place at some time. They had slowly been developing the character. By my second or third episode, I knew I had a last name, and there was some mention of me having a wife or family. I would have been very content to ride it out with them for the run of the show, or until they said, “Hey, Gordy had a heart attack,” or he got hit with a bolt of lightning, since he was a meteorologist. [Laughs.] But bottom line is: It was a great experience. I can’t look back at one day on that set when I didn’t spend it laughing, or at least being in a mood where I was ready to laugh.

So Good Times remains one of my favorite comedies of all time, because when it was at its best, it stood shoulder-to-shoulder with any of Norman Lear’s shows. You alluded earlier to some of the negative aspects of the show for you, but I’m wondering, overall, what your main recollection of the show is four decades later?

I remember — I couldn’t forget — the fact that Norman was probably the most courageous producer/writer/director that had come into television. I was very fortunate to get to work for him. We tackled subject matter that nobody touches today, things like seniors being forced to eat pet food because of financial constraints. J.J. getting shot by a gang member. You can’t open the paper today without seeing some subject we covered 40 years ago. I knew I was in a blessed situation. And also, I was carrying the weight of being the first Black father of a complete family, and I carried that responsibility seriously. Maybe too much so. Norman thought I was taking on too much of a burden with it. But it was my responsibility. I knew that millions of Black people were watching. I knew that my own father was watching. My own children were watching. And I was not going to portray something that was less than redeeming.

You were vocal when the show started moving in a different direction, playing to the popularity of Jimmie Walker’s character, J.J.

The writers began to lose focus on my other two children: Bern Nadette Stanis, who portrayed Thelma, and of course Ralph Carter, who portrayed Michael — the militant midget, we called him, because of his political convictions. With their aspirations to become a Supreme Court justice and a surgeon, I thought we could’ve gotten a great deal of mileage out of that. They chose to go for the obvious and the comedic. It started to dissipate into something I wasn’t terribly proud of. I thought there was a little too much buffoonery. And it wasn’t a matter of being jealous of [Jimmie Walker]. I love comedians; I love anyone who could make somebody laugh. But by the same token, I had these other two children in the family, and I felt it was doing a disservice to them and to the image of young people to say, “You guys don’t really matter. We’re more interested in seeing J.J. with a chicken hat on. At least that’s the way I saw it.

It’s what led to you getting fired from the show, right?

I was categorized by Norman as a “disruptive element.” When he made the call telling me I would no longer be with the show, he said that’s how I was described and assessed by the rest of the cast, and certainly the production company — a disruptive element. So they killed me off.

You weren’t alone in your concerns about the direction of the show, though. Based on everything I’ve read, Esther Rolle shared your sense of responsibility to put out the right image to viewers.

She’d come from very modest circumstances. I think Esther didn’t get her first pair of new shoes until she was 13 or 14 years old. She knew deprivation, and she knew hardship. So her reaction to playing that character was based in truth, as mine was. We always felt that we would be the ultimate litmus test for the veracity of the dialogue and the character situations. I remember having a [conversation] with her, and telling her that we were going to have to stick together and make sure that what we felt about the characters, and their integrity as a family, became a bond with us. And she had no problem with that.

The show was built around a character she had first played on All in the Family, but from what I’ve read, she was very interested in having another strong adult character on the show to play opposite.

Were it not for Esther Rolle, quite frankly, I would not have gotten the job as James Evans. She insisted that she have a husband on the show. She did not want to perpetuate the negative stereotype of another matriarchal family. She told Norman, “I want a husband. I want a husband who works. And I don’t want him to be an alcoholic or druggie. I want a husband who’s going to be a family man.” And when I got to read for her, for Ms. Rolle and Norman, in his office, at the conclusion of the reading, she turned to Norman and said, “He’ll do just fine.” And that’s how I got the job as J.J.’s daddy. I thank Esther to this day for the opportunity.

If there was any upside to your exit from the show, it was that it gave Ms. Rolle one of her most iconic moments on the series— when she broke down in the kitchen after your death and screamed, “Damn, damn, damn!” I’ve always wandered if you watched that episode. It would’ve been strange to see your character mourned like that!

It’s a very rare experience. [Laughs.] Not too many people get to see their own funeral. I saw the episode years and years ago. It’s still a mystery to me how my character died. It’s a matter of conjecture. Some people say he died on the Alaskan pipeline. Some say he died in a truck crash. All I know is that I died. And hopefully there was some insurance for the family.

Your departure from Good Times also made you available for Roots. It’s being remade for next year, and LeVar Burton is associated with it. Any feelings about whether this is a good idea?

All I know about it is that LeVar is onboard as a co–executive producer, and that Laurence Fishburne has been cast as the late Alex Haley. I’m curious about how they’re going to do the story this time. Are they going to do a replication of the original, or is it going to be a new script? I have faith it’s going to be done right, though, because it’s a Wolper project. Mark — David’s son — had the rare privilege of learning at his father’s knee what goes into a project to make it the resounding worldwide success that Roots became.

Ms. Rolle quit Good Times a year after you were fired, in part because she had many of the same concerns you did about the direction of the show. Did you ever talk to her about her decision to leave?

She never expressed to me personally why she left the show. But it was obvious. And from what I was able to infer from the articles I read, she left the show after I’d been killed off the show. She thought it was going downhill into an area of buffoonery and away from what her intentions were initially. But the show suffered so badly in the ratings, they brought her back for one more year, and then the show ultimately went off the air.

You’ve put the whole experience behind you and made up with Mr. Lear, right?

I certainly did. It was a matter of me maturing, and [understanding the impact of] the posttraumatic stress syndrome I’d suffered as a result of playing football and boxing. Once I’d matured, I’d realized the mistakes I’d made in addressing my grievances about scripts. Everything to me at the time was confrontational. I was younger, I was angry, I was mad at the world. I wanted to right every wrong with every line. And they got tired of it. I told Norman to his face, when I was at an event honoring him, “I would have fired me, too.” Because life’s too short to put up with somebody who’s unhappy on a job where they’re making an incredible salary and receiving the acclamation of millions.

How is your relationship with Walker?

I’m not angry at anybody. Jimmy is a hardworking comic, and he is a good comic, as evidenced by the fact that he’s had a long career. In regards to any personal differences we had at the time, that’s over and that’s behind me. I try to look forward. He’s a welcome guest for dinner in my home any time he decides to stop by.