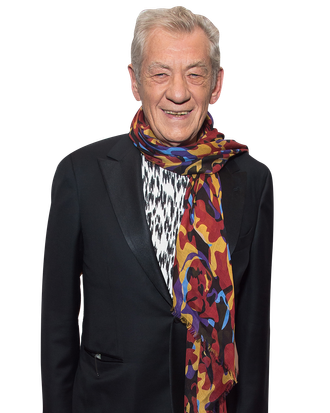

A few weeks ago, at the end of a brutal Los Angeles heat wave, I met up with Ian McKellen at the Chateau Marmont, where he was the only one not breaking a sweat. It helped, of course, that the 76-year-old McKellen was dressed casually in a youthful blue T-shirt and white sneakers, clothes that were a far cry from the smart period tailoring of Mr. Holmes, the summer indie smash that had him in L.A. for an awards-season push. In that Bill Condon–directed film, McKellen plays an aged-up, late-in-life take on Sherlock Holmes, and in our far-ranging conversation we talked about the movie, how McKellen cracked a film career, and holding hands with cute boys.

The last time you were nominated for an Oscar was in 2002, for the first Lord of the Rings movie. I remember it well, not least because you brought a hot young man as your date.

We sat in the front row and held hands. People told us that, at least. I wasn’t aware we were holding hands … we were just out on a date, weren’t we? [Big smile.] Obviously the director of the show was gay, and saw this. Other gay people saw it. And the world becomes a better place.

It was meaningful to me because at that point, it was rare for any famous actor to be openly gay. Have any actors who’ve since come out thanked you for it?

Well, younger actors, yes. I think actors of my generation just think, “Oh, McKellen is bellyaching on again about gay rights. Shut up!” What they don’t realize is that there are people who need to hear that message. I don’t know about you, but it seemed to me that coming out makes one receptive to other people’s problems. You are aware that your own problems with being gay, visited on you by society, make you sympathetic to people who you’ll never meet in other countries where even worse conditions prevail. I mean, I’ve just had to turn down a lifetime achievement award at the Dubai Film Festival because it is the law of the land that you must not be gay. And a visiting gay person who makes a fuss — and by “fuss” I mean, be themselves — will be thrown in jail or deported. That’s not the happy environment in which you want to receive a present.

Your first Oscar nomination was for 1998’s Gods and Monsters, directed by Bill Condon. It took you almost 15 years to work together again, but now you’ve made two films back-to-back: Mr. Holmes, and Bill’s upcoming re-do of Beauty and the Beast, starring Emma Watson and Dan Stevens.

Was it that long? Well, we always said we’d try to do something else, and he called me up one day and said, “I think I found it.” So, that was that. I don’t develop things of my own. There’s no point doing that, takes too much time. It’s true that I did suggest to him, “What am I playing in Beauty and the Beast?” And he said, “Play the clock.”

And how are you playing the clock? Do they cover you in dots for motion-capture?

No, not me. Some figures are animated, like the clock, but then the clock becomes a human being at the end. So, all I had to do was the bit where I woke up, and [the rest was voice]. Other people have dots, I think. The Beast, he had to be in one of those suits.

They painted dots all over Dan Stevens? That’s unfortunate.

[Laughs.] Well, that’s what they do. Fortunately I didn’t have to worry about that. I wouldn’t mind doing motion capture. It’s interesting, but it’s not come my way yet.

In those 15 years since you and Bill worked together, you signed on for two franchises, and his career skyrocketed, too. Did it change your working relationship to get back together after so much success?

I suppose we were both a bit more confident. We got better at our jobs because we’d done a bit more work. But we’d been friends all that time. Whenever I went out to Middle Earth — which was a lot, over a number of years — I would always stop, break the journey here, and stay with him here. So, we had kept in touch with each other. We both thought, “Aren’t we lucky that everything is working out?” He was making the sort of varied movies he wanted to make, big movies and small movies — and the same for me, really. But, as people, our relationship was just good pals. You know Bill, he’s so engaging. He knows exactly what’s going on in every department, but he’s not a control freak, so he casts very well. You don’t really see a bad performance in a Bill Condon movie. It’s the sign of a good director.

You spent much of Mr. Holmes acting opposite the young actor Milo Parker. Do you feel that working with a child brings out something different in you?

[Long pause.] I’d rather work with grown-ups.

There are certainly less restrictions on their time.

Well, there’s that. And with another actor, you can talk about what you’re doing — there’s a shared language. But you couldn’t talk to Milo about that. It’s only the second time he’d been on a film set! Are there any bonuses? Well, he’s a very particular little boy, and he was very good at being particular. He never got in the way. He wasn’t a brat. I think all child actors are taught to be nice to the grown-ups, and he certainly was. But it was artless, what he was doing. There was no cunning to it. There didn’t have to be, and it would have been awful if he had known what he was doing, but he had enough native wit. No complaints at all, but on the whole, it’s easier working with adults.

Well, the artlessness is interesting, because I would guess that when a person starts acting, he would operate more on intuition than intellect. Did your own approach to acting evolve over time?

I began to be interested in acting as an audience. I wanted to find out how they did it, I wanted to be backstage, I wanted to be behind the camera. How’s it done? Where’s the best place to stand on the stage? How do you rehearse? Things like that. And the only way to find out was to do it myself, so I started acting! And I think when I decided to become professional, my only aim, really, was to get better as an actor.

What do you gauge “getting better” as?

Well, finding it easier. I had to learn how to be funny. It’s not easy.

Comedy didn’t come naturally to you?

It’s not easy to be funny, for me. And you can only be funny if you are absolutely truthful. So, I’ve learned how to do that. It was all at the service, to begin with, of me as a gay man who wasn’t entirely open about being gay, in a job where your only requirement was to be truthful. I was able to express myself in my work in a way that society didn’t want me to express myself in real life, and when I came out, I completed that journey. When there was nobody in the world I minded knowing I was gay, everything made sense. Relationships made sense, family made sense, and acting became not about disguise, but about revelation. So that was the big thing that happened, just at the time I was beginning to be allowed to be in movies.

You phrase that like Hollywood wasn’t letting you in.

My impression of the first 20 years of acting was that I was very happy being a theater actor, although I did do films, none of which were successful. And watching contemporaries like Albert Finney and Tom Courtney and Alan Bates and Anthony Hopkins, who were all thriving in the film industry, I thought, “Good on them, but they’re not playing Macbeth with Judi Dench. They’re not playing King Lear at the National Theater of Great Britain and going on a world tour.” I thought I was very happy doing that, but now my friends say I was always going on about, “Why aren’t I in movies?” You’re not always a good witness to your own life.

So how did that change?

I know exactly how it happened. We had been touring Richard III from the National Theater, and when we landed in this town, I finished the screenplay and spent two years raising funds to try and get that made into a film. In between time, I visited other people’s movies. I was with Arnold Schwarzenegger and his only flop, Last Action Hero. I worked for James Earl Brooks, a tiny little part. I was in Cold Comfort Farm, one of John Schlesinger’s last films. All the while, I was trying to figure out, “How do I act in film?” I asked all those directors, “Show me how to do it.” They never did. You’re on your own, really. And then Richard III came, and it worked, and that was like a huge calling card. It was like taking out a full-page ad in Variety.

And then they came to you.

I was considered respectable, I think, and Bryan Singer called me in, having seen that, and asked would I like to be in Apt Pupil. And then he said, “Oh, I thought you were older. You’re too young. What a pity.” And then we chatted. It was here, at the Chateau. And he said, “Have you seen John Schlesinger’s new movie, Cold Comfort Farm? Who’s the guy who plays the old preacher in that?” I said, “That was me.” He said, ”What? Oh, you can play older?” So he put me into Apt Pupil, he put me into X-Men. That wouldn’t have happened if it weren’t for Richard III.

And in Mr. Holmes, here you are again playing older.

Always playing older. At university, I always played the old parts. I actually thought, If I’m going to be a professional actor, I’ve got to do the difficult thing, which is to play your own age. No disguise. That was hard for me when I wasn’t secure about myself.