The recent release of Ork Records: New York, New York — the newest excavation from archival label Numero Group, known for its subcultural archaeology — proves that not every stone had been left unturned when it came to punk rock. The boxed set resurfaces every single released by one of the first punk and indie labels in its prime (1976–1979), placing influential, albeit lesser-known, acts (the Feelies, a post–Dead Boys Cheetah Chrome, The dBs) alongside debut releases from what are now marquee names (Television, a post-Television Richard Hell, Big Star’s Alex Chilton).

At the center of it all sits Terry Ork, the bearish and eternally grinning founder of Ork Records and early manager of Television, who followed Andy Warhol to New York from his native San Diego, where Warhol was filming San Diego Surf in 1968, just before an attempted assassination on Warhol. During the film’s production, Ork — a film lover and a gay man — started to ingratiate himself with Warhol and his coterie. After several years around the Factory, however, Ork faded out of the “It” social circle, left with little but a surplus of charisma and a love for the avant-garde. He parlayed both into his pseudonymous record label. Equally important, though a little later in the story of Ork Records, was Charles Ball, the more business-minded one, who did his best to whip a drain-circling do-it-yourself label into the shape he felt it deserved, in a proto-DIY era, no less.

Nearly every resurfaced artifact of New York’s first-wave punk scene has been welcomed with a wave of nostalgia that can make the present feel somehow less-than, if you let it. The past, by comparison, seems like a petri dish of salt and dirt and concrete that schooled cool, brilliant people. Every kid with a chip on their shoulder, on all sides of the Hudson River, knows the broad strokes of punk’s birth (on this side of the Atlantic, at least). From the glue-sniffing apathy of the Ramones, to the lipstick-trace insanity of the New York Dolls, to the philosophical bounce of the Talking Heads, essentially, the scene was fucked-up near-children making hard music in a hard city, wholly unconcerned with their own longevity. That it all coexisted both temporally and socially is delicious thing, but it can be limiting. Thinking that the scene around CBGB (or Max’s Kansas City, or whatever your iconic venue of choice may be) simply can’t happen now in a new, exciting form — that it was an artistic Valhalla free of worry and cancer and consequence — robs the present of its possibility. It’s a useless recreational impulse — convincing yourself that you missed all the important stuff — but it’s a familiar waste of time to rock-and-roll fans, at least. By that logic, spending my own teenage years obsessing over early punk’s desperate screams starts to resemble an act of regression, not some novel protest.

With all this in mind, I reached out to David Godlis, a photographer who was in close orbit around Terry Ork and Charles Ball during their most productive stretch in the late ‘70s, not to mention other formative punks who lined the Bowery back in those days. Needing a link to the past to dispel this strain of nostalgia, I wanted to go back in time with Godlis on the East Village streets of today. Godlis documented the era with as distinct an eye as his subjects; his early work was jittery, character-driven, and took place well after the sun had set. (Fittingly, Godlis will release History Is Made at Night, a book of photographs from CBGB, this spring.)

“It can’t be,” he says of this particular pastime (yearning for a bygone golden era). “It’s the same way people wait for rents to go down. I had a good time with a bunch of people in a place at a time when things were a certain way. When you were in CBGB, you felt safe.”

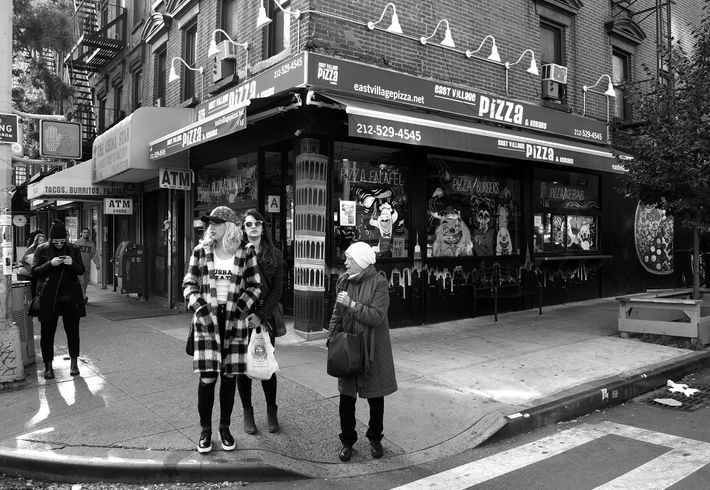

On Halloween afternoon — one that grew increasingly surreal, as sailors and Iron Men steadily grew in number across lower Manhattan — Godlis and I met up on the corner of St. Marks Place and Second Avenue and ended up walking for six hours, retracing the paths of photo shoots and visiting former punk haunts he hadn’t visited in 35 years. As we walked — north to 17th Street, then zigzagging south into Chinatown — the current chain-store milieu of New York revealed itself to be filled with life, just not the kind Godlis and his ilk led. With Godlis’ sarchive of original shots at hand, that juxtaposition becomes even clearer.

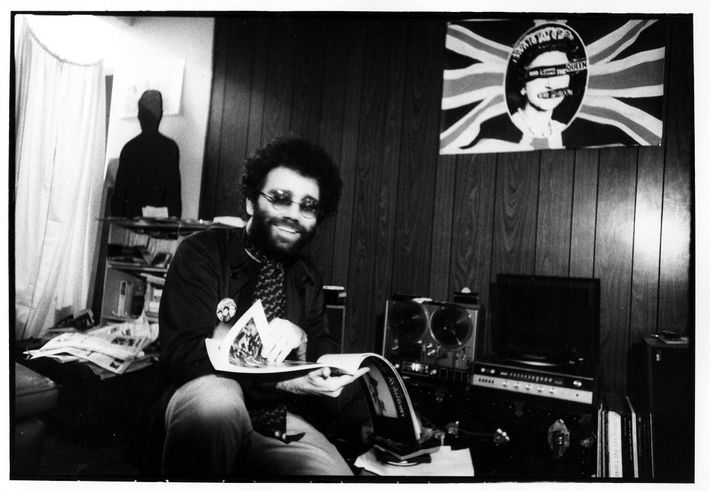

Charles Ball’s Apartment: 59 St. Marks Pl.

“It still looks the same, that’s what I love.” As we stand in front of the building where Charles Ball held court, a woman nervously ducks in the front door, closing it quickly behind her as Godlis points his camera. “He smoked pot, he played me music. We’d argue constantly. Charles was argumentative, he was a Mensa-smart person. I didn’t know until years later, after he died and I spoke with his brother, that he aspired to be a photographer. So he’d constantly tell me what I was doing wrong.” Godlis says that a project of Ball’s, in which he wanted to compile a cross-section of the clamorous, nihilistic, and self-aware No Wave scene, which arrived simultaneously as part of and as a reaction to the still-active punk scene in the late ’70s. In contrast to punk’s punch to the face — which then morphed fully into the shimmy of New Wave once the major labels got their hands on it — No Wave offered an eye-roll and a broken bottle. Ball’s compilation was pulled out from under him by none other than Brian Eno. “Eno had the better record deal, so he took these bands and put out No Wave New York.”

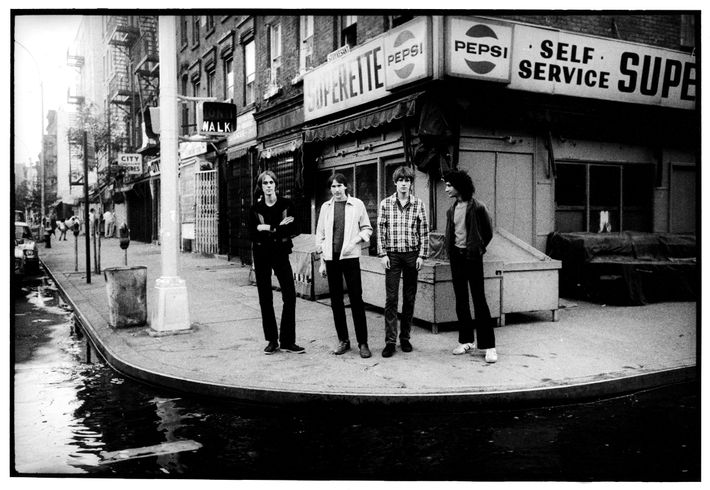

Television Puddle Photo: E. 9th St. at First Ave.

“The drain obviously didn’t work, there had been a storm of some sort. Or maybe they didn’t have fuckin’ drains. The street was at this odd bend, unattended to. They must’ve thought I was crazy — I mean, nobody cared it was Television I was photographing.” Godlis is like a methodical hummingbird, backing up into traffic and bicycles carefully, comparing the picture he took 35 years ago to the street before us as passersby stared and giggled. Two grown men yelling across tourists and costumed children will do that. When he finally finds the correct angle, you can see the post–Richard Hell lineup — Tom Verlaine, Richard Lloyd, Fred Smith, and Billy Ficca — in front of you, awkward and unknowing that their debut, 1977’s Marquee Moon, would eventually garner classic-album status.

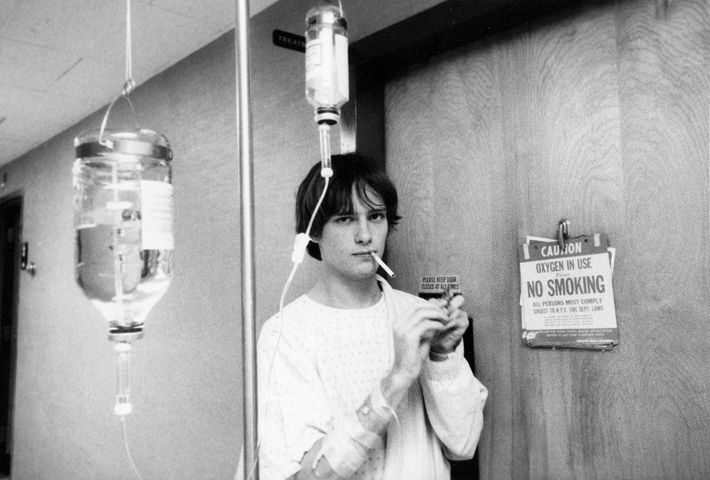

Beth Israel Hospital: E. 16th St. at First Ave.

We continue up First Avenue, toward the hospital where Television guitarist Richard Lloyd, to this day a friend to Godlis, was taken after getting “dope sick.” As we walk, Godlis mentions The Legend of Nick Detroit, a fumetti starring Richard Hell as the titular Nazi-fighting spy (and co-starring David Johansen, Debbie Harry, David Byrne, and Lenny Kaye); I’m unfamiliar with the term fumetti. “What they would do in Europe, magazines would have black-and-white pictures and use cartoon bubbles to tell a story. Punk magazine imitated that, with photographs of punk stars to create a story.” As it turns out, punk rock owes a bit to the insane aesthetes of mid-century Europe, particularly French New Wave — a term appropriated by Godlis and Co. to name the nascent scene in front of them. Those artists’ headfirst leaps into creation, done so with little regard for the patience or preparedness of their audiences, have a clear through line of inspiration to New York’s downtown rock scene in the ’70s.

As we reach Beth Israel, Godlis remembers traipsing the halls with Ork, Lloyd, and Lloyd’s girlfriend Judy during Lloyd’s stay. They mounted a photo shoot, involving IV-bag fuckery and copious amounts of cigarette smoke, that would be shut down immediately these days. “When we went back to his bed, Richard was selling pot,” Godlis says. “He was weighing out the pot for someone and had the curtains pulled, we were inside. The guy next door is asking, ‘What’s going on in there?’ Richard says, ‘None of your business. Shut up!’” Across the street from Beth Israel lies the original Stuyvesant High School, which Lloyd attended. Even in the past, the past is strange.

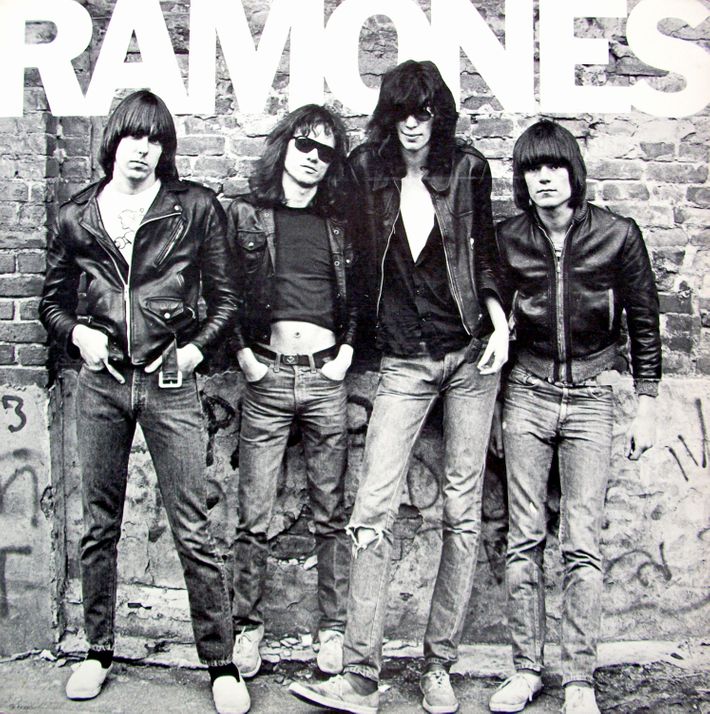

Hudson’s: E. 13th St. at Third Ave.

“Hudson’s was the only place you could get ‘em,” Godlis says, referring to the black jeans and Keds (not the Chuck Taylors you might have expected) that the Ramones sported on the cover of their first album. Punk’s favorite surplus store is now a bar called the Penny Farthing, while a Think! Coffee across the street has replaced the porno theater where Robert De Niro’s character in Taxi Driver popped in to pass the time.

“Hudson’s had a lot of things that were left over from the last era, from the ‘60s,” Godlis says. “Levi’s wasn’t making black jeans, but there were plenty in stock.” Fashion is in the fabric of New York City, but its connection to punk gets fuzzy around the time hard core took over in the early ‘80s, a scene in which a less-considered wardrobe was de rigueur. Blondie’s taste in T-shirts and the Ramones’ plimsolls defined the eyes through which you saw them, but in later incarnations of punk, you were considered kind of a poseur if you cared too much about how you dressed.

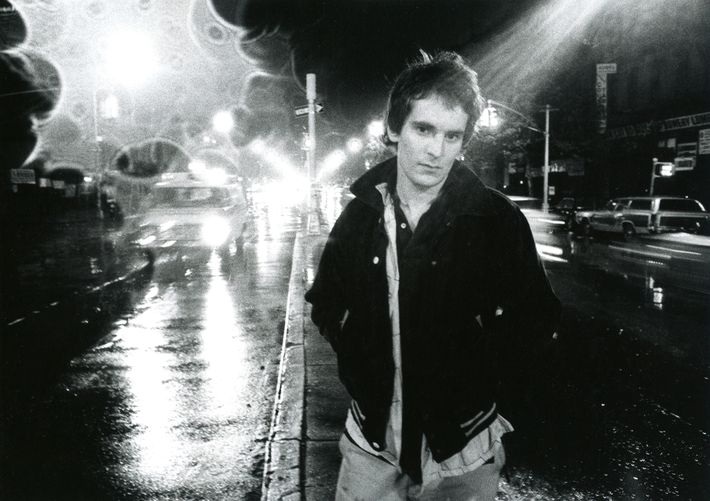

Alex Chilton on the Bowery: E. 1st St. at Bowery

Though Alex Chilton isn’t exactly a household name, his playful rock with Big Star, the Box Tops, and solo would go on to influence countless bands. The Replacements would name a song after him, and put the track on Pleased to Meet Me, the record where he ended up joining them in the studio. At the time of Godlis’s portrait on the Bowery, Chilton had the respect of his peers but remained widely unknown.

“[Famed Memphis-born photographer] William Eggleston knew Alex Chilton’s parents,” Godlis says. “The thing I spoke to Alex about was photography. Eggleston did one of the pictures for the ‘Singer Not the Song’$2 7-inch on Ork, and I did the other side. It was an honor.” In the picture, which also appears on the cover of Holly George-Warren’s biography of Chilton, he stands on the median in the middle of Bowery right near CBGB, his eyes the only thing piercing through the dreamlike haze of headlights. “A raindrop had fallen on my lens, and I didn’t realize it.” When I ask about the characterization Chiton receives in the extensive liner notes of the Ork Records boxed set — that he was drunk and broke and miserable — Godlis says he saw none of it. “He was happy, playing music. He really liked the whole punk thing.” I had never associated Chilton with punk, but as it turns out, he was — like everyone, I’ve come to realize — a lot more punk than most of the punks I grew up with.

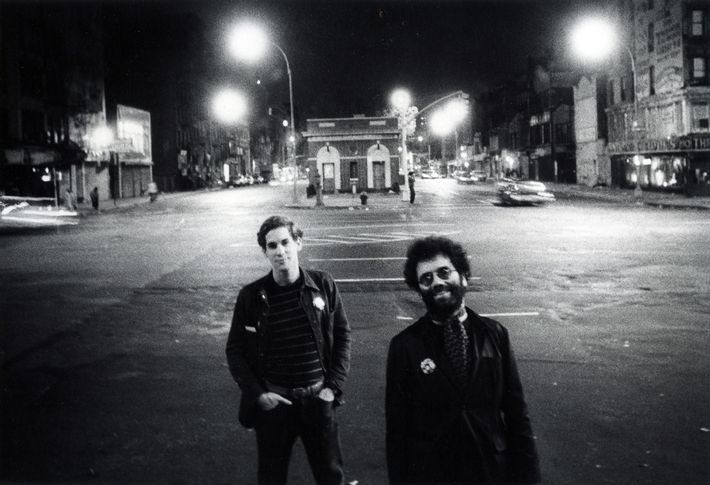

No Wave Punks: Outside CBGB (176 Bowery)

“The guy on the far left? Nobody knew who he was,” Godlis laughs. “Turns out he’s a friend of Thurston Moore, and he hated all these bands. Thurston told me later, ‘That should’ve been me in that picture!’” That this group of high-minded noisemakers had a turd in their midst feels all too appropriate, considering the scorn they brought to their creativity. Also pictured (from left to right): Harold Paris; Kristian Hoffman, future keyboardist for Lydia Lunch; Diego Cortez, who would go on to curate the ahead-of-its-time MoMA PS1 show “New York New Wave” in 1981; Mudd Club co-founder Anya Phillips, nearly all of Teenage Jesus and the Jerks (including No Wave’s de facto leader Lydia Lunch, James Chance, Jim Sclavunos, and Bradley Field); and Liz Seidman, who many years later would produce The Rugrats Movie (among other animated features).

Cinemabilia: 10 W. 13th St.

Given Terry Ork’s obsession with French New Wave, Cinemabilia was a fitting birthplace for his label. Filled with esoteric prints and books documenting the cinema revolution that had taken place in Europe in the previous decades, the shop drew in the young and the curious, like Richard Hell, who worked under Ork’s management there. It is now one of four Beacon’s Closet thrift stores around the city. “What can you do with this,” Godlis asks, shrugging as customers mill for late-minute Halloween costumes. “Nostalgia is just history to me. I don’t want everything to be like it was when I was at that age … but I’m happy it was.”

Ramones Cover Shoot: E. 2nd St. at Bowery

Godlis’s friend Roberta Bayley was the one responsible for the Ramones’ now-iconic first album cover, but serendipity strikes, so we pop in. The garden that houses that stark brick wall, now a sickly off-brown beige, is open for the last time before closing for winter. Godlis is thrilled: “This is never open!” He hands me his camera, and I take his photo against the wall. As we wander the little garden, its groundskeeper — a mouse of a man with a New York accent thicker than the bricks he tends—- tells us: “That’s the wrong spot. You’re doing the Ramones thing? Yeah. Wrong. It was over there.” We can’t take a step without encountering a metaphor. We also can’t stop laughing.

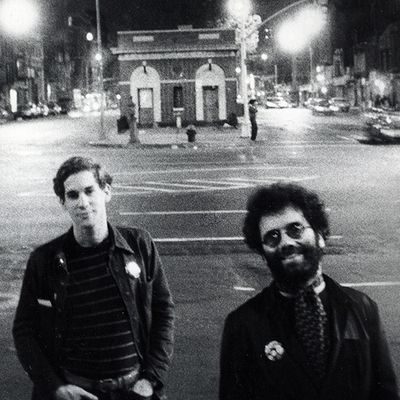

Boxed Set Cover Shoot: Allen St. at Delancey St.

It’s easy to see why the Numero Group chose the photo they did to cover the Ork boxed set. A smirking Charles Ball, hands half-tucked into his jeans, stands just behind and to the left of Ork, who’s sporting sunglasses at night like the cool-guy jester he was. The pair look like they know a secret, but would be happy to share it with you if you asked. “Terry was always game for a portrait. Both of them were.”

Terry Ork’s Mysterious Loft: E. Broadway at Market St.

We end the day trying to locate the location of Terry Ork’s loft, where both Richards Lloyd and Hell practiced, and where many doped-out nights were spent. Godlis had asked his famous friends for its exact location, but they could only remember the broad strokes. We wandered West on East Broadway, through Chinatown, attempting to re-create the mental state of the drunk and drugged, who would make their pilgrimage south on Chrystie toward Ork’s at the end of the night.

Godlis seemed overwhelmed by the end of our day — you could see it in on his face, a kind of weary wonderment for what he’d been part of decades ago. “I have a lot to think about now,” he says as we part ways. It was the same for me, except I had been retracing the construction of my early personality, which was assembled in part through the music of Godlis’s real-life friends and subjects. The day had dismantled the last scraps of reverence I held for this scene, like flipping the back cover of a just-finished novel you couldn’t put down. We can talk again, I thought to my imaginary friends, but next time we’ll be the same height.