Patti Smith’s Horses, which turned 40 this week, is such a perfectly formed rock-and-roll artifact that it’s difficult to imagine that Patti didn’t just wake up like that, walk into Electric Lady Studios, and birth one of the most seminal records in music history. The reality is that it took her several years of exploration and experimentation before she reached that point. Patti wasn’t afraid to try something to see if it fit, or even just to do something for the hell of it. So she read her poetry as an opening act for glam rock bands; tried her hand as a cabaret act, wearing a satin halter top and a feather boa; worked as a rock critic for CREEM and other publications; acted in Off–Off Broadway plays and co-wrote one herself; joined a Parisian troupe of street performers. She wanted to try out different forms of art and performance, and she did so fearlessly, realizing that finding out what she didn’t like was almost as important as finding out what she did. Here’s a rundown of her sundry pursuits on the road to her crucial debut.

1967: Bookselling

Patti arrives in New York City because — as she recently reminded David Remnick during the New Yorker Festival — she needed a job. She started at Brentano’s, and then had a grueling stint as a cashier at F.A.O. Schwartz during the Christmas season. Next, she was hired to work in book restoration at Argosy Books, because she was always hanging around the store, but had no experience or aptitude for it. It was only then that she ended up at the legendary Scribner’s on Fifth Avenue, where she worked her way up from phone sales to the main sales floor. And later she would work at Strand Books downtown on Broadway, right up until she went into the studio. (Patti would say later that she always thought that she’d go right back to the bookstore once Horses was done and dusted, and had no idea that it would propel her into an actual career.) Patti often returned to see her co-workers at Scribner’s, who in turn hung her Rolling Stone cover on the door of the break room.

1969-71: Off-Off Broadway

Warhol star Jackie Curtis would see Patti hanging out at Max’s Kansas City, and would hire her based on her look and attitude to perform in Femme Fatale, Curtis’s play at the Theater of the Ridiculous. Despite Patti’s self-deprecating retelling of that time in Just Kids, the actors who worked with her remember quite the opposite: They insist she had stage presence and charisma, and also that she took direction well. This led to Patti being cast in other performances at La MaMa and the American Place Theater. These weren’t mainstream productions in any sense, but were important to a certain downtown crowd, and provided Patti with valuable cache and underground cred. She would also later note that acting gave her an inkling of what it felt like to stand on a stage and command an audience, and she decided she liked that aspect of it, although she found acting itself too confining.

In 1971, Patti would co-write and co-star in the play Cowboy Mouth, along with then-paramour Sam Shepard. Her involvement in this production would be short-lived (when Shepard returned home to his wife), but Cowboy Mouth continues to be revived, and still generates extreme reactions in its audiences.

1969, 1972: Paris

Patti traveled to Paris twice, in 1969 and then again in 1972, for extended periods of time. In 1969, she and her sister Linda arrived in the city for the first time, staying in the Hôtel des Étrangers, where her poetry heroes Arthur Rimbaud, Paul Verlaine, and Charles Cros met. They stayed for three months, Patti drawing and writing. They joined a troupe of street performers, Patti playing a toy piano (which would later accompany her when she read poetry at the Mercer Arts Center). In 1972, she came back nursing a broken heart, this time looking for Jim Morrison’s ghost. Patti would have an epiphany resulting in the prose poem “jukebox cruci-fix,” later published in CREEM, notable for how many of the themes and lines showed throughout Patti’s future work. Her love affair with Paris would continue throughout the years, and France would make her a commandeur in the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres, an award granted for “significant contribution of the French cultural inheritance.”

1971–2: Spoken Word

Patti had shown up at random poetry open mics around the Village before getting her big break opening for Gerald Malanga at the Poetry Project at St. Mark’s Church in February 1971. And she continued reading after that appearance, most notably as an opening act for the half-dozen or so glam bands that performed regularly at the charmingly named Oscar Wilde Room at the Mercer Arts Center, an alternative theater that rented out its stages to rock bands. Patti would read poetry to open for bands like Teenage Lust, Ruby and the Rednecks, and most notably the New York Dolls. She made $5 a night for approximately 10 minutes of work; sometimes, much of that 10 minutes consisted of putting down hecklers, other times her brash delivery and unorthodox subject matter would get through to the crowd. It helped her begin to develop her rock-and-roll stage presence, not to mention her ability to marshal a snappy comeback.

1971–73: Proto–Rock and Roll, Blue Oyster Cult Edition

Patti’s quasi-rock-and-roll performance at St. Mark’s Church raised her profile as a talent to be reckoned with, drawing the attentions of various impresarios and tastemakers, who tried to enlist or at least direct her attentions. Producer-songwriter Sandy Pearlman was managing a new band called Blue Oyster Cult, and tried to get Patti to join up — even just as a songwriter if she didn’t want to be a performer. She would end up co-authoring a few songs along with BOC’s Allen Lanier, with whom she would also have a long-term relationship, but she would never officially or unofficially be part of the band.

Additionally, artist manager and club owner Steve Paul would try to align her with his latest project, a guitarist named Rick Derringer; they would co-write one song together, and get some promotional photos taken, but the project didn’t go any further than that. He also tried to pair her with his other act, Johnny Winter, telling her to give up the poetry and focus on rock and roll; that suggestion went nowhere. It would have been all too easy to jump at the first or second chance of mainstream music-industry sponsorship and potential stardom, but the experience made her all the more sure about what she didn’t want. In fact, it made her more willing to fight for what she believed in doing.

1971: Rock Writer

In the fall of 1971, CREEM Magazine would take the unprecedented action of publishing three of Patti’s poems together, as well as recruiting her to review albums for them as a freelancer. She reviewed Bowie’s Heroes, Dylan’s Planet Waves, the Velvet Underground’s Live ‘69, and Todd Rundgren’s A Wizard, A True Star, among others; she wrote essays on her love for the Rolling Stones (“The Rise of the Sacred Monsters”), and about Jim Morrison’s posthumous An American Prayer. Her poetic style meshed well with the publication’s irreverent and anti-establishment attitude. She would also write a few pieces for Rock Scene, Crawdaddy, and Rolling Stone, and briefly work as an editor for a publication called simply Rock. Patti left the latter during an interview with Eric Clapton, in which she allegedly realized she was less interested in asking Clapton about his work than telling him about hers.

1972–3: Published Poet

Just Kids was most people’s introduction to Patti Smith as a writer, but she was a published author even before she signed her record deal. Seventh Heaven came out in 1972, a slim volume of work containing 22 poems. It was published on downtown imprint Telegraph Books, known for its consistent cover style and affordable prices. Another slim volume of approximately 20 poems, WITT (pronounced white), would be released in 1973 under the auspices of Gotham Book Mart.

She would also release a handful of chapbooks (small, paper-covered volumes with generally no more than 20 pages) in this time period, the most interesting being Ha! Ha! Houdini, a single poem written as a tribute to the magician; some versions of the chapbook were locked together by a small padlock. (The keys were included with the package.)

1973–74: Cabaret at Reno Sweeney’s

Reno Sweeney’s was a small theater in the Village at the forefront of what the New York Times politely referred to as the 1970s’ “cabaret revival,” hosting entertainers like the Manhattan Transfer, Bette Midler, and Peter Allen. Into this seemingly incongruous context stepped Patti Smith, accompanied by Lenny Kaye on guitar. She dressed the part, wearing a black, satin halter top and a feather boa (yes, really), and presented a set list mixing poetry and cabaret songs: Cole Porter’s “I Get A Kick Out of You,” “I Ain’t Got Nobody” (best known from when Louis Prima combined it with “Just a Gigolo”), and Hank Williams’s “Annie Had A Baby” were some of the numbers presented as an opening act for Warhol superstar Holly Woodlawn.

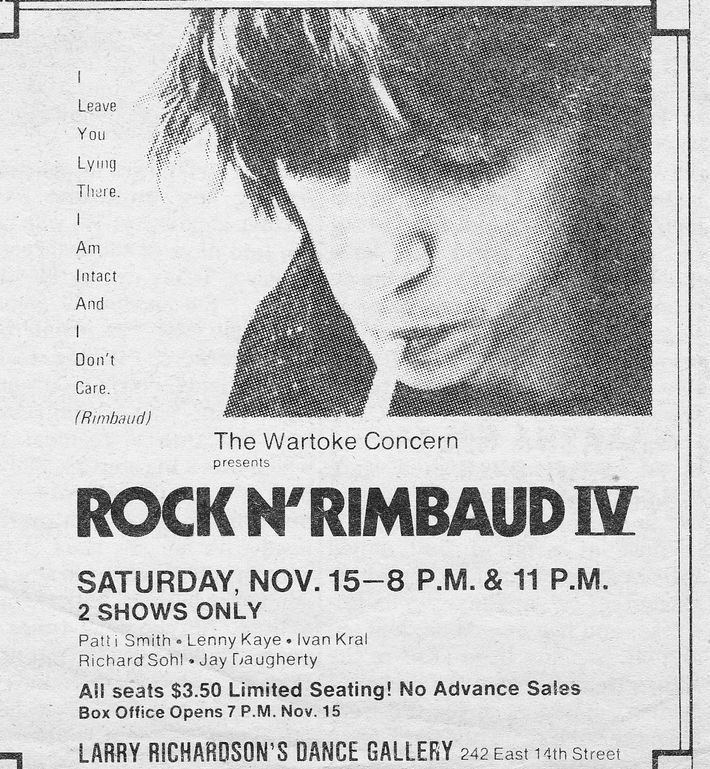

1973–75: Rock n Rimbaud

After the Mercer Arts Center (literally) collapsed and before the discovery of CBGB’s, artists were exploring other venues around the city in order to have somewhere to perform and to try to start something, anything, anywhere. Patti’s answer to that was what she called “Rock n Rimbaud,” a combination of music and poetry, working off the foundation she’d established at her initial St. Mark’s Church reading with Lenny Kaye a few years earlier, adding a few more musicians each time. She would organize four of these events, the last one at the end of 1975 (“2 shows only! All seats $3.50. Limited seating. No advance sales.”)

1974–75: The Patti Smith Group

Patti had continued to perform with Lenny Kaye on and off, creating a solid partnership. By the spring of 1974, they began to look for a keyboard player to augment what they now realized was turning into a band. They found Richard “DNV” Sohl just prior to a two-week opening slot at Max’s Kansas City. Second guitarist and bassist Ivan Kral was recruited the following year, in time for the band’s defining seven-week residency with Television at CBGB’s. And finally, drummer Jay Dee Daugherty would join up in the summer of ‘75, not very long before the band would enter the studio to record Horses. The band would remain central to Patti’s rock-and-roll identity until the very end, and Lenny and Jay Dee would resume their roles almost immediately when Patti moved back to New York in 1995 following semi-retirement, effectively resuming her public life and live performances.