Trumbo is a film that at times can’t seem to decide what it wants to be. At its worst, it’s musty and awkward; at its best, it’s irreverent and funny. Unfortunately, it settles for the former more than the latter: Arriving with all the attendant baggage of Oscar bait, it’s an Important movie, about an Important subject, and real Important historical events. But you wish its goofy spirit would shine through more often.

The acclaimed author Dalton Trumbo (Bryan Cranston) was Hollywood’s highest-paid screenwriter in 1947, right as the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) came calling. In the 1930s, during the Depression and the spread of Fascism in Europe, many artists and socially conscious individuals had flirted with Communism; in Trumbo’s case, he had actually joined the party and continued to be a member. Being a Communist wasn’t illegal, of course, but Trumbo and nine other writers and filmmakers — the so-called “Hollywood Ten” — who refused to testify before HUAC were held in contempt of Congress, and Trumbo wound up going to prison for nearly a year. Afterwards, he was blacklisted from writing films under his own name, and had to stand by and watch as his pseudonymous screenplays for Roman Holiday and The Brave One won Oscars. (In the early 1960s, when Otto Preminger hired Trumbo to write the screenplay for Exodus, and Kirk Douglas announced that Trumbo had written Spartacus, it marked the effective end of the blacklist era in Hollywood.)

Trumbo dutifully breezes through many of these historical touch points, but it’s mild on the politics. Asked if he’s a Communist by his young daughter, the writer plays it coy. Instead, he uses an anecdote about a sandwich to illustrate the notion of sharing with those less fortunate. (The girl, we are assured, will gladly split her sandwich with a friend who doesn’t have anything to eat — instead of telling her friend to get a job, or loaning the sandwich to her friend at an extortionate interest rate — which basically makes her a Communist, too, according to this film’s politics.) John McNamara’s script also doesn’t dwell too much on the nuances of the political battle lines in Hollywood at the time. Though we do get a decent John Wayne impersonation from David James Elliott, and archival footage of sympathetic witnesses like Ronald Reagan and Robert Taylor speaking before Congress, the film lays the blacklist mostly on the shoulders of the admittedly loathsome gossip columnist Hedda Hopper (Helen Mirren), who makes a convenient media boogeyman here. Watching the film, you start to wonder if she was solely responsible for the Red Scare and for perpetuating it in Hollywood. There’s a certain amount of condensing that’s required of any historical movie, but in this case, the script reduces much of this period to shallow, smug clichés.

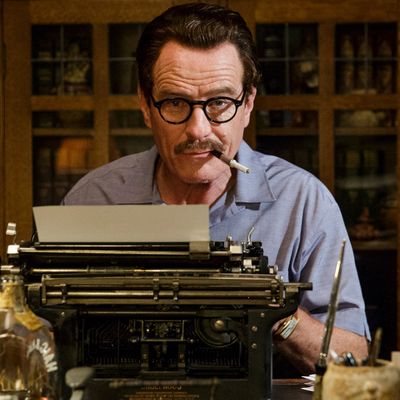

That’s the bad news. The good news is that Trumbo is mostly well-acted, and it perks up in its later scenes. Cranston has a tough job here. His character has a gruff, wisecracking exterior, but he’s mostly a hero and martyr, a man whose own infinite patience and goodwill are matched only by those of his angelic family (in particular his wife, played by Diane Lane). Still, Cranston gains our sympathy, in part because of his physical transformation — there’s a certain frailty to Trumbo, a physical awkwardness that pulls you in. At the same time, the film isn’t afraid to give us lots of shots of him sitting around writing — it helps that he often wrote in the bathtub, a glass or bottle of Scotch by his side — and Cranston effectively shows him thinking, and creating.

Trumbo’s director, Jay Roach, has in recent years won acclaim for his cable movies about political events (Recount and Game Change), but his talent lies in comedy; he made his name with the Austin Powers films and the wonderful Meet the Parents. Maybe that’s why Trumbo comes to life when, after his stint in prison, the writer starts working under pseudonyms for low-budget B-movie impresarios the King Brothers (John Goodman and Stephen Root, both wonderful). Here, the facile politics takes something of a backseat, and instead we get a charged, vibrant spoof of Hollywood wheeling and dealing — funny, fast, and engaging. And briefly, Trumbo becomes the film we suspect it should have been all along.