The Netflix musical-variety special A Very Murray Christmas doesn’t amount to much, yet it’s sublime; maybe it’s sublime because it shows no evidence of needing to make any kind of impression. It moseys across the screen, occasionally helping itself to a cookie or some eggnog, and every few minutes somebody sings a song. As written and co-produced by Murray, Scrooged co-writer Mitch Glazer, and director Sofia Coppola — who gave Murray one of his signature roles in Lost in Translation — it might as well be the fantasy of one of Murray’s earliest beloved characters, the lounge singer Nick from Second City and Saturday Night Live. That character’s hepcat facetiousness was a cover for the depression he surely felt at having to perform for handfuls of bored and distracted patrons in railway-station bars, airport cocktail lounges, and Army bases in Greenland.

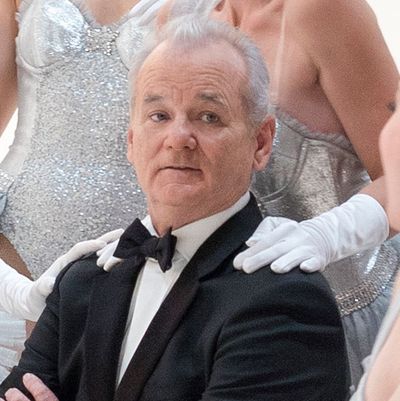

Murray stars here as Bill Murray, or “Bill Murray.” He’s the headliner of a musical-variety special that was set to be broadcast live from New York City’s Carlyle Hotel on Christmas Eve until the blizzard of the century shut down the city. (Not that anyone in show business, even 1970s-era Nick, would agree to that kind of gig — but because the whole special is a trifle that runs less than an hour, you roll with it.)

An array of celebrities drifts through. Some play characters: Michael Cera as an agent who wants to represent Murray; Amy Poehler and Julie White as the special’s dogged producers, who think they can hide the fact that the audience is empty by cutting to close-ups of people attending last year’s Golden Globes ceremony; Jenny Lewis of Rilo Kiley as a cocktail waitress who duets with Murray on “Baby It’s Cold Outside”; Jason Schwarztman and Rashida Jones as estranged fiancés. Others play “themselves”: George Clooney shows up very briefly, playing Dean Martin to Murray’s sad-sack Sinatra. Chris Rock just happens to wander by and gets drawn into a duet of “Do You Hear What I Hear?” even though, by his own admission, he can’t sing — not that that stops most of the other guests, nor should it; this is more of a “hanging out with friends who won’t judge you” kind of musical special. Karaoke, basically.

When a ringer with pipes shows up — like Miley Cyrus, whose cover of “Silent Night” is so lovely that for a moment you might wish the special had been built around her, with Murray as a guest star — it’s a pleasant surprise. She’s one of two show-stealers here. The other is Maya Rudolph as a guest who tells Schwartzman, “Love’s got an up button and a down button, and you gotta decide which one to push,” then belts Darlene Love and Phil Spector’s “Christmas (Baby Please Come Home).”

While A Very Murray Christmas isn’t substantial enough to be considered a serious statement on anything, it’s not a spoof either. And as you unfold your arms and decide to enter into the world it creates, it starts to feel like a statement about the mania for making statements — either serious ones about the True Meaning of Christmas and the State of Humankind, or spoofs of that sort of thing. Never for a moment do you feel that anything is at stake, just as you never feel that anything is at stake when you’re hanging out with friends and somebody who can play the piano sits down at the keyboard and starts picking out a melody that everyone knows. It’s a lot handsomer and more fussed-over than some of the 1960s and ’70s variety specials that partly inspired it: Most of the scenes set in the Carlyle have the mahogany-rich visuals of Coppola’s feature films, and a dream sequence near the end boasts Technicolor-bright hues and defiantly artificial indoor “snow” sets. Paul Shaffer is the true, secret star of every scene. Whether the performer he’s accompanying can sing brilliantly or not at all, he’s always right there with them, grinning like he can’t believe that after all these years, he still gets to do this for a living.

As is often the case with Murray’s comedy, it’s impossible to know exactly how kidding or serious he is, and this, too, is integral to the special’s energy, which seems lackadaisical at first but eventually comes to seem quite controlled and purposeful in its near-aimlessness. For 40 years now, Murray cornered the market on a particular brand of self-aware postwar showbiz energy. He’s conscious of all the tricks and clichés of entertainment and italicizes them to make sure you see them, too, then somehow pushes past all that to find something sincere. Pauline Kael wrote that in Ghostbusters, Murray somehow stood outside the story even as he occupied its center — that he wouldn’t even commit to being in the movie. There’s some truth to that, but I’m not sure it quite captures the essence of Murray’s comedy, which would seem purely fatuous were it not for his sandblasted Emmett Kelley face, the vulnerability expressed in his quieter line readings, and those crying-on-the-inside eyes that Coppola, Jim Jarmusch, and Wes Anderson have put to such haunting use.

The final shot of this special, a profile close-up of Murray’s face looking out over the New York City skyline on a winter morning, is somehow devastating, perhaps because you’ve spent an hour in Murray’s company, watching him goof around and sing and worry and flip out, yet you still have no idea what makes him tick. Does this special’s “Bill Murray” have a family? What kind of person would commit to doing a live TV special on Christmas Eve? We don’t know, and answering that question is nowhere on this show’s list of concerns, but you still look at Murray’s face and wonder. There is a haunting loneliness, or aloneness, to so many of Murray’s characters. Some part of them will always remain unreachable, by choice.