Vulture is talking to the screenwriters behind 2015’s most acclaimed movies about the scenes they found most difficult. Today we spoke to writer Drew Goddard, who adapted Andy Weir’s novel The Martian for the screen, about how hard it was to get Matt Damon into act three while still being faithful to the book’s scientific acumen.

With The Martian, I knew that the challenges came from the fact that it’s a very dense text, and the science is very dense, and you have to make it accessible for an audience. I knew that would be the question that came up over and over. I felt like, All right, just trust that if I love it, other people are going to love it, too.

My job became much more about protecting what was in Andy Weir’s book. I said to the studio, “Don’t come to me and say we have to dumb this down. Because if we do, I don’t know that we have anything.” If we have to strip all that out, suddenly we’re left with a Robinson Crusoe story. Which is okay, but it wouldn’t be special the way I think the movie is special. The intelligence of the book is key to its success. It was all about finding that balance. For me, the secret was: As long as we’re relating to Matt Damon, we’ll go along with the exposition. But that was always the challenge: finding ways to make each scene human so that the science had context.

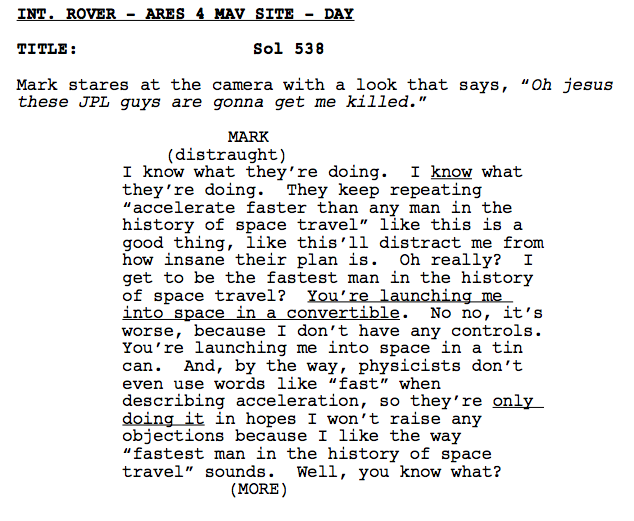

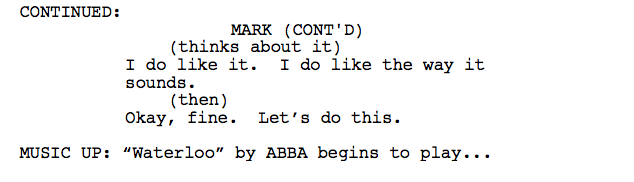

There’s one scene that stands out as being especially difficult. I essentially called it the “Matt sets up the third act” scene, and it’s just a monologue. We had this concept of what the third act is, which is that we’re going to launch Matt into space in a tin can. That’s it. When we explained that that was going to happen, we needed to explain why, and we needed to explain the velocity involved in what’s going to happen, because one of the things that’s hard about filmmaking is speed can be difficult. For example, if you look at race cars on tracks, you need to see them blowing past something to understand that they’re moving at a high rate. It’s perspective. The problem with launching off the surface of a planet is, we really wanted to sell how dangerous all of this was about to be. It was this exposition that I was struggling with, of just Matt Damon talking.

It wasn’t until about the tenth draft of it that I hit upon this idea of Matt saying, “I’m being manipulated. I know they are just repeating to me ‘fastest man in the history of space travel’ over and over because they’re trying to trick me into doing it.” Frankly, it just made me laugh, but I liked that it actually gave us an arc for this scene. He starts in one place — “I know I’m being manipulated” — and then by the end of it, he falls victim to the manipulation. It was one of those things that makes me like the character. As opposed to exposition, it became a character arc for him to say, “They’re right, I do like the way that sounds, let’s do it.” That gave me a guideline.

I was so excited, and I called Andy and said, “I think I’ve cracked it.” He very dryly said, “Eh, that doesn’t work. A physicist would never use the word fast.” I’m like, “Andy, you’re such a bummer right now! I’ve finally made it simple to understand that he would be the fastest man in the history of space travel — that’s something that will work!” And Andy’s like, “What do you want me to tell you, Drew? A physicist wouldn’t use the word fast.”

I hung up thinking I was going to have to start another draft — and then I thought, let’s just put that in the scene. Let’s just put Matt Damon saying, “A physicist would never use that word, I’m just being manipulated.” It was just a conversation between Andy and me, but it really crystallizes the process of the whole movie, where I would be dumb and Andy would correct me and then I would put that correction in the pages of the movie. It’s just a half-page scene, but it’s really satisfying to me because of Matt Damon and the way he’s able to go from A into B so by the end of it you have “Waterloo” kick in, and we’re off to act three.