The first episode of the second season of “Serial” had the tentative, almost conservative quality necessary for a good setup. Keep the narrative simple — in this case, an unquestioned account of Bergdahl’s version of events — so that it’s easier to complicate down the road. But also hint at a few larger themes you’ll be exploring. Then you can start letting the oppositions and inconsistencies drive the show forward. And the second episode provides a fascinating example of a compelling antithesis to Bergdahl’s “horses mouth” narrative: the Taliban’s version of events.

Koenig is pretty casual about interviewing a Taliban soldier. After giving some updates on Bergdahl’s impending court-martial (apparently he’s refusing to cut a deal because he wants the chance to give his version of events so that he’s not “misunderstood”), the episode flatly moves into the phone call. Her source, referred to by pseudonym, participated in the hiding of Bergdahl and knew that he was a score. Kidnapping is a revenue source for the Taliban, and an American is worth more than just any old foreigner. And an American soldier is worth more than just any old American. At one point, Koenig’s Taliban source estimates that Bergdahl was worth “more than 5,000 individuals.” His appraisal works the same as it would on a piece of antique furniture in an auction house. Bergdahl is worth as much as the Americans are willing to give for him. The Taliban understands that the Americans are willing to sacrifice a lot for Bergdahl.

Koenig hypnotically weaves together the accounts of a trusted journalist and her own source inside the Taliban. The picture that emerges is a sort of counterweight to Bergdahl’s self-spun capture story: He was found inside or near a nomad tent. Nomads informed the Taliban that a foreigner was in the area. When the Taliban arrived to check it out, they told Bergdahl that they were the police, and he immediately jumped behind their motorcycles, as if seeking protection from them. They called Bergdahl a “ready-made loaf,” a gift that had fallen into their hands without their having to work for it. Bergdahl fought a little at first, but he was pretty easily subdued.

Here we hit our first real point of departure from Bergdahl’s own story. Our first muddying of the narrative. Koenig actually brings the momentum of the episode to a halt in order to point out the difference between the Taliban’s and Bergdahl’s versions of events. And she says that there will be more to come, discrepancies that are impossible to fact-check. But the implications of the divergences are huge. If Bergdahl really was actually inside a nomad’s tent, asking questions about Kabul, it’s entirely possible that his purpose wasn’t to cause a DUSTWUN as a way to the blow the whistle on bad leadership. But at this point, it’s the word of Bergdahl against the claims of a handful of Taliban soldiers.

The Taliban’s narrative itself is fractured and full of contradictions, and it occasionally sounds like rumor. Bergdahl is reported to have fought back, or maybe not. Lots of people said he was drunk. Some said he was crying. Some said he was laughing. They called him “weak and brainless.” Others thought maybe he was a martial-arts expert. One guy compared him to a baby cat, another to Buddha. But they had no idea why he left his base. And neither do the Americans. In fact, this is where certain interesting parallels begin to form between the gossip about Bergdahl spreading through the Taliban, and the rumors being picked up by American surveillance and disseminated among American soldiers. In the first episode, one platoon mate of Bergdahl’s says he thought it was a possibility that Bergdahl had been an undercover CIA agent, and that theory isn’t any more fantastical than the stuff being picked up by American intelligence on Low-level Voice Intercept, or LLVI, technology, which pulls radio and cell-phone signals from the air. The big questions are never about Bergdahl’s whereabouts — the Americans know the Taliban has him and are fairly certain he’ll be taken to Pakistan — but his motivations. Both sides seem perplexed, and they speculate wildly in a vain attempt to fill what looks to me like a mental-illness-shaped hole.

As the DUSTWUN took effect, the search efforts ballooned, and every other operation in Afghanistan was put on hold. As Koenig says, it’s a basic “ground floor” principle of the American military to account for every person, to never leave a man behind. From my own experiences, that ethos was drummed into my head during basic training. The seventh line of the “Soldier’s Creed” is “Never leave a fallen comrade.” But in the mind of the average grunt, there’s a world of difference between a “fallen comrade” and someone who intentionally walks off of their post. A bond of trust is broken. Platoon and company mates of Bergdahl’s very seriously tell Koenig that, had they found him, they might have beat the shit out of him or worse. And for a brief moment, after hearing about how units all over Afghanistan conducted something resembling a “mini-surge” to find Bergdahl, spending weeks at a time out in the field in an almost uninhabitable climate, I shared their frustration with Bergdahl. I sympathized with the guy who, risking his life and shivering at night in the cold, was asking himself if Bergdahl was worth it.

At the same time, I have to sympathize with the pariah. During my first deployment to Iraq I wrote a few dispatches for The New Republic that made me a pariah in my own unit. I suffered for it. I was made to work 20 hours a day in the brutal Iraqi heat, cut off from social connections and conversation. I built a parking lot. I moved a junkyard from one end of base to another. And I was eventually hospitalized with typhoid. I passed through a crucible and eventually worked my way back into the good graces of (most of) my brothers. But being ostracized hurts when you’re part of a small, tight-knit unit — and so like Dave Pajo sings, “I can see myself in both of their eyes.”

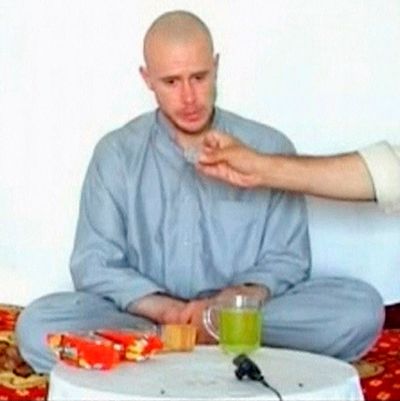

In another interesting parallel, the Taliban also have a sort of ambiguous relationship with Bergdahl. They don’t consider him innocent or a pawn. No one forced him to travel halfway around the world to invade their country and kill Muslims, but they do consider him a “guest.” Obviously the term is used loosely, but it means that no one is going to beat or kill him. Koenig’s Taliban source had been imprisoned by the Americans at Bagram for two years and wanted to treat Bowe better than he himself had been treated. They even stop off at a winery at one point and conduct a traditional dance in a bid to raise Bergdahl’s morale. It scares the shit out of him. A cynic might say that one reason Bergdahl wasn’t killed right away is that the intense effort of the Americans to find him gave the Taliban reason to believe he was someone important, not just a private first class. The Americans were so off mission, so far from respecting the tenets of counterinsurgency operations, that the Taliban had every reason to believe this.

It wasn’t true that Bergdahl was a big deal in the sense the Taliban were thinking — but he was important. There was a cultural and political imperative for the military to do everything it could to find him. But as the American military plodded around the country, it got played by intel plants and always found itself a step behind the action. The Taliban, meanwhile, was nimble and light, and had home-field advantage. There just wasn’t a very good chance that Bergdahl was going to be found.

An interview with Jason Dempsey, a former major in the 10th Mountain Division, is the highlight of the episode, and it really puts a fine point on the inadequacies of the American military in Afghanistan. We have, Dempsey claims, zero institutional knowledge for the military in Afghanistan. Sure, we’ve been there for a long time. It’s now America’s longest war. But when “being there” consists of units rotating in and out of the country without building any sort of permanent single consciousness, for lack of a better term, in the country, our roots aren’t deep enough to learn anything of real substance. We don’t understand the “complicated politics of the towns.” We have no idea what’s going on “on a granular level.” And the implication of this, something borne out in my own experiences, is that there was an institutional culture of underestimating the complexity of Middle Eastern culture. This is, to my mind, where the episode really starts to achieve escape velocity. Koenig’s promise of zooming out to see a bigger picture starts here, in this scathing critique of our military’s systemic failures, lucidly expressed in the story of its initial inability to locate Bergdahl.