A few hours after word broke of Glenn Frey’s death Monday night, Bob Seger paid tribute to his old friend by claiming, “Make no mistake about it: He was the leader of the Eagles.” The notion that the Eagles had a lone leader comes as a bit of a shock because Frey always appeared joined at the hip with Don Henley, the pair crafting their country-rock aesthetic, writing songs together, and steering the band through contentious lineup changes. Through it all, the Eagles seemed like a joint affair, not the work of a lone gun.

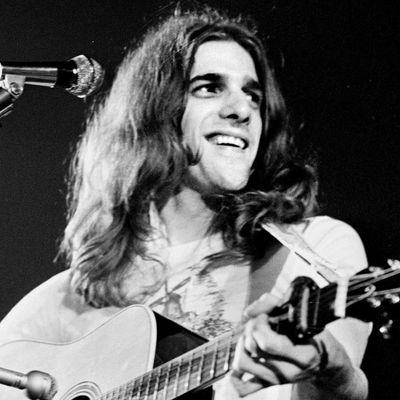

For better and for worse, Henley exudes such a heavy gravitational pull in the Eagles that it’s possible to think of Seger’s statement as little more than the kind words of a comrade. But old Bob’s onto something. Henley might’ve provided the Eagles with ballast but Frey gave the Eagles lightness, adding a bit of a soulful lilt while maintaining allegiance to the driving rock and roll of his native Detroit. If Henley harbored aspirations of being regarded as a serious singer-songwriter, Frey liked playing in a band. He played in plenty of them as a kid in Detroit, knocking around in a bunch of garage-rock combos before he headed out to the West Coast. Even at the height of the Eagles’ stardom, Frey still seemed to get a kick playing loud guitar.

Such joy counterbalanced Henley’s sour disposition. Where Don looked upon Los Angeles with disdain, Glenn celebrated all the good times that happened under the golden sun. Frey loved California the way that only a transplant could. He didn’t linger in SoCal’s seedy alleyways and side streets so beloved by Tom Waits and Warren Zevon. He preferred the beach and deserts that bookend Los Angeles while also treating himself to all the spoils of Hollywood.

Hollywood looms large in the legacy of Glenn Frey. He spent much of his ‘80s appearing on television — he had his own episode of Miami Vice in 1985 and a regular role on 1989’s Wiseguy — and racking up hits on movie soundtracks. “The Heat Is On,” from 1984’s Beverly Hills Cop, gave him his solo career, but by that point, the guitarist already was ensconced in the ethos of Los Angeles. Occasionally, the Eagles would sneer upon the excesses of L.A., most famously in “Hotel California,” a song so mean-spirited it invited Satanic conspiracies in the ‘70s and ‘80s, but also in the melancholy sway of “Hollywood Waltz” (both notably sung by Henley, not Frey). Yet no matter how loudly they protested, the Eagles came to embody everything that was SoCal sleazy in ‘70s rock and roll. Some of this reputation was blowback for their own bad behavior and mercenary instincts, character flaws accentuated by an adversarial music press. Such tales hardened the attitude of listeners who otherwise might have not given the band a second thought. The Eagles weren’t simply hated for their music: They were hated for what they represented, the moment when the promise of the ‘60s curdled into corporatism.

To an extent, this is true. The Eagles weren’t a group of schoolmates who formed a gang and set out to tackle the world — they were expatriates who wound up gigging for money in Southern California, eventually crossing paths as a supporting band for Linda Ronstadt. Sensing a good thing, Frey and Henley turned this into its own enterprise and the duo always retained an air that they pursued this venture as a business opportunity; they were a partnership, not a team. Old hippies viewed the group’s streamlining of Gram Parsons’s Cosmic American Music — turning it into something smooth and urban, lacking even a nod to the electrified twang and snap of Bakersfield — as tantamount to betrayal. That’s the context that underpins the Dude’s dismissal of the band in The Big Lebowski; it’s implied that hating the Eagles wasn’t a matter of taste, it was principal. Similarly, after the group splintered in 1980 — all the tensions culminated in a Long Beach show where Frey told guitarist Don Felder it was “only three more songs until I kick your ass, pal” — the solo careers of Frey and Henley crystallized how rock had turned into another commodity that could be sold and bought with efficiency.

Such criticisms contain a germ of truth — the Eagles aligned themselves with two of the great businessmen in rock history, label head David Geffen and manager Irving Azoff — but in order for this business plan to work, there needs to be a product to sell. This is where Frey excelled. As a tonic to the stoic Henley, Frey provided the Eagles with their lightest, breeziest hits — the songs designed for the open road. “Take It Easy,” the group’s first single, set them down that endless highway in 1972, and Frey handled its turns with ease, establishing a pattern he’d follow for the rest of the group’s life. He’d dabble in hard rock — “Chug All Night” on the eponymous ‘72 debut could stand alongside Seger — but Glenn would wind up striking radio gold with the songs that felt a little softer and sweeter, whether it was the smeary heartbreak of “Tequila Sunrise” or the twilight plea of “New Kid in Town.” Sometimes, the Frey-fronted singles did indeed rock — “Already Gone” glides along with the force of a jetliner, while “Heartache Tonight” defines the big beat of pre-MTV arena rock — but often his skills as a rocker lay behind the scenes, helping to arrange Eagles songs for maximum effect.

Listening to the solo work of Frey and Henley, it’s easy to appreciate what they each brought to the table. Without Glenn, Don succumbed to ponderous sobriety; for all their debatable attributes, Henley’s Building the Perfect Beast and The End of the Innocence lack the succinct snap Frey brought to Hotel California and The Long Run. On his own, Frey wasn’t particularly ambitious, opting for defiant nonsense like 1982’s “Partytown” or seductive soft rock like “The One That You Love.” Such shamelessness was the key to Frey’s charm: Whether he was mugging through the video for 1985’s “Smuggler’s Blues” or praising the power of fitness as he did on 1985’s wannabe anthem “Livin’ Right” (seriously), Frey favored good-time rock and roll. His decision to embrace every neon-lit indulgence of the Reagan era underscores how his journey was that of a quintessential baby-boomer. He didn’t set the times so much as he reflected them, moving from the hazy hippie hangover toward clean-cut professional, eventually returning to the role he loved best: the singer, guitarist, and leader of the Eagles.