I am a pathologically nervous flyer, and once, on a short flight out of Berlin, of all places, gripped by a manic and totally unfounded certainty that the plane was going down, I listened to David Bowie’s “Heroes” five, ten, maybe 20 times in a row. As I reasoned in the moment, that is the song I’d choose if I had the opportunity to soundtrack my own death. I calmed my nerves with Bowie’s unruffled-by-anything croon and a bleak but oddly soothing mantra I sometimes find myself using on planes: “It is pointless to worry, because we are almost always felled by the thing we don’t expect.” This mantra has turned out to be true every time I’ve used it — so far, at least. The plane landed. I lived. On the ground, the notion of soundtracking my own death seemed morbid, impossible, absurd.

And yet I awoke this morning to the creeping yet somehow comforting feeling that David Bowie — the exception to every mortal rule — got to do it, and beautifully. Tony Visconti, who’s lived for the past 18 months with the secret that David Bowie was dying of cancer, issued a statement today in which he called his friend’s death “a work of art.” Bowie left us with a gorgeous and gloriously strange record, Blackstar, released just three days before his death, which critics rightly praised even before they realized it was his swan song; it now stands as recorded proof that he remained vital and darkly funny and nimbly open to new ideas even in his final year of life. I wrote about it last week, for an issue of the magazine that comes out today, and it chills my blood to think of it circulating through the city this morning, bearing words of mine that talk about David Bowie in the present tense. Even more unsettling are the remnants of my research scattered around my apartment: One of the first things I saw when I opened my eyes this morning were two freshly dog-eared Bowie books on my nightstand, his mercurial alien’s smirk gently mocking my human grief from their front covers. When I reached for my iPod, the song I’d listened to last punched me in the gut: “Ashes to Ashes.”

I’ve spent the past few weeks immersed in Bowie, revisiting all the albums and rewatching all the movies and asking my dad to repeat his story about seeing the Ziggy Stardust Tour in Philadelphia so I could get jealous all over again. Bowie knew how to live like a rock star better than possibly anyone who’s ever breathed, so is it facetious to think that he also knew how to die like a rock star, orchestrating his reentry into our consciousness with elegance, bravado, and impeccable timing?

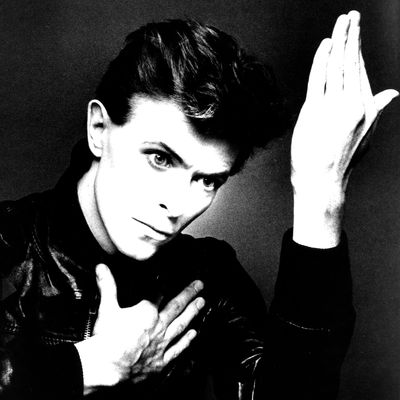

This morning, my social media feeds were all monopolized by solemn links and RIPs and the most iconic images of Bowie. I respect that some people grieve this way, but for today, at least, it feels like something I’m not ready to do. After my morning coffee, I signed out of Twitter and Facebook and went around the corner to buy him flowers. I dug out the journal I kept in Berlin and found a quote I’d copied down from the still-touring “David Bowie Is” exhibit I’d seen there, about the notorious 1970 cover of The Man Who Sold the World, on which Bowie is splayed out on a fainting couch wearing a dress: “It was too controversial for the American market and was replaced by a cartoon of a cowboy and a gun.” I hung above my desk my favorite souvenir from that trip, a postcard of a 1978 sketch Bowie had drawn of himself, from the cover portrait of Heroes. I lit a candle below it. I cried for him like a friend.

I don’t think we fully realize what an intimate connection we have to the musicians we love until we lose them. My Bowie grief feels at once collective and also incredibly private, impossible to explain. The obituaries are trickling in; here come the heated debates about the best Bowie record and whether or not he was better than the Beatles or the Stones or both of them combined. I’m not ready for that today. I’m not even ready to confront the full contours of his voice in the harsh intimacy of my headphones. The best I can do is put on “Heroes” in the other room and let it drift over to where I sit, like a muffled dream.

I lost someone close to me in his early 20s, the kind of person who acted when others hesitated, who traveled to the places he dreamed about, who did instead of didn’t. Maybe I’m crazy or sentimental, but in recent years, I’ve come to suspect that he knew. Like some kind of angel or devil had materialized at some point and whispered in his ear exactly how much time he’d get, and he took this information as a blessing rather than a curse. He got to work. At the risk of sounding crazy or sentimental all over again, I found myself feeling this morning like David Bowie knew, too. And he took the news with that stirring mixture of melancholy and motivation with which he sang of Earth’s death sentence on Ziggy Stardust opener “Five Years,” the only song that comes close to expressing what I feel today. Sixty-nine years. That’s all he got. But good God, look at what he did with them.