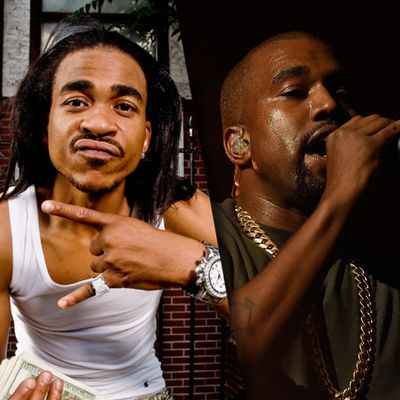

If you’re reading this, chances are you lost part of yesterday to Kanye West’s Twitter feed and its attendant fallout. In short, West was looking for an excuse to lash out at Wiz Khalifa, and thought he found one in an acronym he misinterpreted. What started as a delightfully petty dismantling of poor Wiz’s career devolved, in the space of about ten minutes, into gross insults aimed at his and Khalifa’s mutual ex, Amber Rose. The whole ordeal — from West’s warning shot to the lethal retort from Rose — took no more than two hours. Now, the day after: The tweets have been deleted, the story codified, the audience bored and on to Anti. So the news cycle goes. Waves, in stores February 11.

But outside of the suffocating bubble of Twitter, time doesn’t always move so quickly. What are you doing in the fall of 2042? Barring a miracle release, Charly Wingate, better known to the rap-listening world as Max B, will be preparing for his first parole hearing. If all goes according to plan, it’ll happen a full 33 years after he was convicted in 2009 on an array of murder, armed robbery, and other charges for his role in a botched 2006 New Jersey heist. (He wasn’t in Jersey at the time, but prosecutors tried him under conspiracy laws; meanwhile, Gina Conway, Max’s ex-girlfriend who testified against him at the trial, has since claimed her original confession was involuntary and should not have been used by police.) November 2042 is 26 years from now. He’ll be 64.

I bring up Wingate because he, at least on the surface, was the catalyst for yesterday’s Twitter theatrics. When West initially said, two nights ago, that he was changing his new album’s title from Swish to Waves, Wiz responded in no uncertain terms: “Please don’t take the wave. Max B is the wavy one. He created the wave. There is no wave without him.”

“Wave,” like most great slang, expands and contracts as Max sees fit, describing first his flow, then his hair, then everything his sunglassed eyes surveyed. And while no person could be said to reasonably own tides or improper nouns, Wiz isn’t wrong. Despite only a half-decade in hip-hop (the only half-decade in his adult life that he was a free man), Max made an indelible mark on rap in New York and beyond. His remarkably prolific run more or less lined up with the nadir of New York City in mainstream hip-hop: Nas dropped Hip Hop Is Dead … in December of 2006, and while that sentiment was meant to cater to the city’s conservatives, it was a popular belief. The national music press had shifted its attention to rappers from the South, and the brand of hip-hop that was en vogue was seen by many of the genre’s old guard as a foreign entity. In any event, New York fell out of fashion, and it led to a panic about the city’s place in the culture, a vacuum for rap stars so cavernous that Papoose was tapped as a star in waiting.

But Max was not a classicist or a revivalist. When the Harlem native came home from an eight-year robbery bid, his childhood friend, Cam’ron, introduced him to Jim Jones. The year was 2005, and Cam’s crew, the Diplomats, had grown into one of the best and most important stylistic movements to take a hold of the city after the turn of the century — some would say they were the last one to truly do so. Cam spun his early 2000s buzz into a semi-successful coup of Roc-A-Fella; Dipset made pink Range Rovers menacing and once-vicious foes seem soft. But their aesthetic — chipmunk soul samples and colorful crime tales — was so strong, and Cam’ron so world-beatingly charismatic, it masked the fact that other than Cam, and with all respect to Juelz Santana, none of them truly shone as solo artists. None until Max B.

All the Jim Jones lines you remember from after the Iraq War are Max. So is the hook on Cam’s “You Gotta Love It,” the Jay Z diss song that correctly pins the fall of Roc-A-Fella on “open-toe sandals with chancletas with jeans on.” Where Jones and Santana tried, often successfully, to bore through a beat with sheer will, Max preferred carefully laid beds of warbled harmony. The vocal approach set him apart not only from his Dipset compatriots but from the crudely drawn party lines that were supposed to keep street rap separate from R&B. A decade after his debut, his approach is the baseline for a plurality of popular young rappers across subgenres.

To that point, the two artists to whom Max’s mixtape output is most often compared are 50 Cent and Lil Wayne. The former used the early 2000s circuit to reestablish his cache as a hitmaker, inverting popular songs with sharper, smarter hooks and his hollow point-affected drawl. On the other hand, Wayne — who was becoming the best rapper alive exactly as Max was finding his footing — would make industry tracks his own by upping the stakes immeasurably, rapping more animatedly, more bizarrely, and simply more than anybody else. But Max had the unique ability to make it sound as if producers in Atlanta and Miami and St. Louis and Seattle were crafting records specifically for him, specifically for the wave.

Max’s catalogue is unwieldy, formless. Building any sort of listeners’ guide would be Sisyphean. Do you start with the sparse, scattered Million Dollar Baby Radio? The technicolor Wavie Crockett? Do you want to follow him through the polarized looking glass (or the Benz in the cruise lane), or would you rather hear him play counterpoint to the late Stack Bundles, whose more staccato, precise delivery gives the perfect balance? For a control, what about his extensive work with French Montana?

There’s no easy primer, but you could do worse than to start with the four songs that Wiz Khalifa posted two nights ago: the brash, anthemic “Lip Sing”; the slinking, hazy “Never Wanna Go Back”; “Porno Music,” which is exactly what it sounds like; and “Why You Do That,” which sounds like waking up from a nap with five grand you forgot about. We’ll wait while you listen, because you really ought to if you want to understand what Ye and Wiz are on about.

Though it’s tempting to talk about Max solely as a stylistic innovator, he delighted in being a naturalist with the pen. His vocal abilities just enhanced the experience; his best trick was dipping into monotone at the exact points in verses where the writing got most interesting, so you were always caught off-guard.

It’s even more tempting, evidently, to turn Max into a meme, into a name to scrawl on hastily made T-shirts and to be cited in digital arguments that decay before everyone’s finished typing. What he is is one of the most important New York rappers to debut this century, and someone who’s hoping to be freed while he still has his health and his family. The next time you have a spare weekend or two — and plenty of bandwidth for DatPiff tabs — sink into Max’s catalogue (some recommendations below). The wave is forever.

Million Dollar Baby 2 (2008): Max felt he wasn’t being properly compensated for his work with Jim Jones; to cover his $2 million bail, he fell even further down the rabbit hole by signing over more of his publishing to the elder Diplomat. Million Dollar Baby 2 opens with “Umma Do Me (Jim Jones Diss).”

Public Domain 3: Domain Pain (2008): The stakes feel the highest here — just see the Gothic-dark “We Got Doe.”

Quarantine (2009): The end of Max’s run was when his pop instincts had come into their fullest effect.