In 2007, Jeremy McCarter, at the time a theater critic for New York, wrote a glowing review of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Off Broadway production In the Heights, praising it as “a musical that owes more to Big Pun than to Bernstein.” The following year, having moved on to Broadway, the show was nominated for 13 Tony awards, winning four, including Best Musical.

Despite that dizzying success, Miranda remembered McCarter’s early review, and the two eventually met to talk about their shared interest in theater and hip-hop. But Miranda also had an idea: “He mentioned to me in our very first conversation that he was interested in doing something about Alexander Hamilton, which at first I thought was a really funny joke,” says McCarter. “Turns out it wasn’t a joke.”

McCarter later left the magazine business to run Public Forum, a performance and conversation series at the Public Theater centered on politics, media, and the arts. (Disclosure: I worked with McCarter at the Public.) It was there that the Public’s artistic director, Oskar Eustis, asked him to recommend artists for potential projects, and the first person he could think of was Miranda. McCarter introduced Lin to the Public in the summer of 2011, and, well, you know the rest.

Hamilton is now one of the most sought-after tickets in town, and next up, the show is preparing to go national. Come April, there will also be a book, Hamilton: The Revolution, co-authored by McCarter, who wrote the chapters, and Miranda, who provides detailed annotation to his libretto. It includes profiles of all 11 principals, as well as over 40 different interviews, including several with Hamilton biographer Ron Chernow.

“When Lin told me that there was going to be a book about the show and proposed that he and I do it together, I wasn’t sure what the book could be until I thought about the fact that Hamilton tells the story of a revolution, but it is itself a revolution, and the book could be a way for readers to watch those two revolutions happen in tandem.”

Miranda wrote most of the songs from Hamilton in sequence, so the book follows its creation and its plot in chronological order, beginning in the White House, where the world got its first look at the opening number, “Alexander Hamilton,” and ending on Broadway opening night with “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story.”

“I got lucky,” says McCarter. “One of the fortunate, unexpected things about this book is that I’ve been around the show since before it was a show, and I didn’t have a thought in my head about writing a book about it with its author until he proposed it very late in the process. So a lot of the book is based on things that I got to see firsthand that haven’t been reported elsewhere because nobody else was there.”

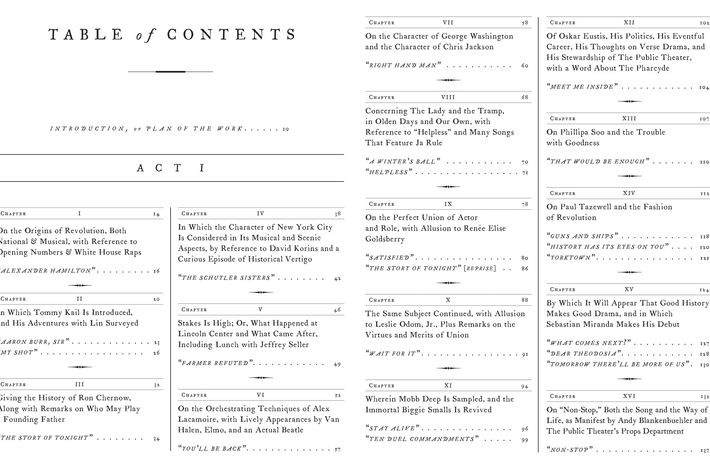

Below, McCarter talks about putting Hamilton: The Revolution together, the clever chapter titles found in the table of contents — premiering exclusively on Vulture — and the stories behind some of the book’s standout chapters.

Figuring out the structure of the book

“Lin wrote the show largely in sequence, so the text of the book is a series of chapters that describe another episode in its development, or share a profile of a person involved in the production, or something essayistic about what it means. It was complicated to put together, but part of the fun of it for me and Lin is that this was like a puzzle: How do you assemble the pieces of this book so that it’s telling a coherent story from page one to page 288, but also setting up the next song in the show, and how do the notes on that song explain that song but also continue the insight that Lin has been giving you in the songs that follow and precede.”

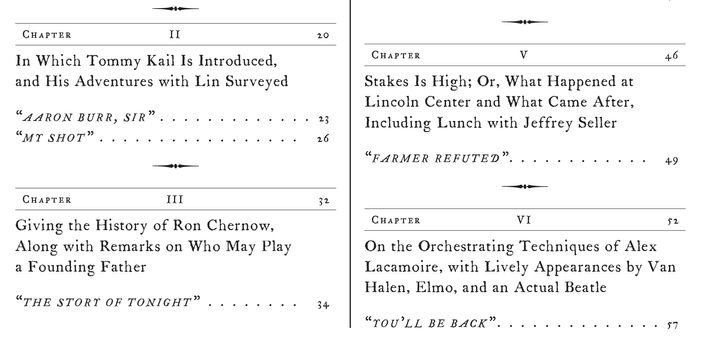

Writing the lengthy chapter titles in the table of contents

“We knew from the beginning that the book ought to evoke Hamilton’s era, and one of the really distinctive things about books back then is the crazy-long, all-inclusive titles, which, it turns out, are stylistically really interesting, but also really helpful because these chapters do include lots of different kinds of stuff. So I asked Tori Spencer of Melcher Media, the company that put the book together, to find lots and lots of tables of contents from books written during Hamilton’s lifetime and asked her to send them to me. I put them all in one place and just looked for patterns that got used a lot.

I then made a catalogue of words that were really used in tables of contents back then. When I was writing the chapter titles, it was almost like Colonial-era Mad Libs to try to accurately describe what’s in this book using primarily or entirely the words that would have been used in the 1790s. On some of them, like Stakes Is High, it’s just too irresistible if you can put the title of a De La Soul album in that old-timey font. I don’t have anywhere near the self-control to resist doing that.”

How Lin approached the annotations

“Lin went in on these song annotations. They’re really smart, they’re really funny. He shed a lot of light on how autobiographical some elements of the show are — even moments that you would never think are related to his own experience. Most of what Lin wrote in the annotations is even new to me, and I was around to watch him work on a lot of it. They’re very personal. It’s a mix of technical stuff, of jokes, of references to other shows and rap albums. It’s about his life, and how his experiences shaped large things and small things in the show. They shed an extraordinary amount of light on what you’re hearing.”

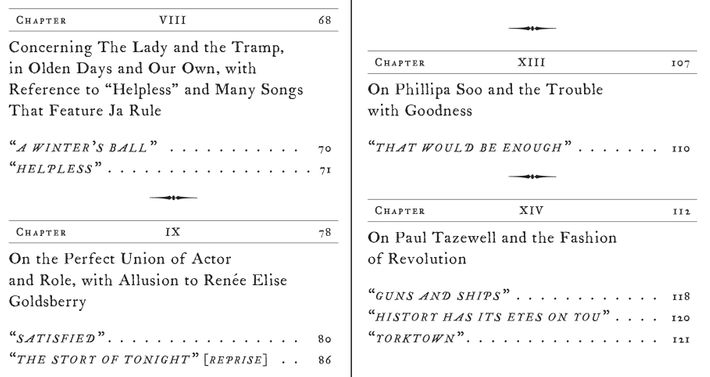

On Chapter XIII: “Concerning the Lady and the Tramp, in Olden Days and Our Own, With Reference to ‘Helpless’ and Many Songs That Feature Ja Rule”

“At some point, the first time they sent us preview pages to show us the layout, I remember seeing Ja Rule’s name in that font that evokes the 18th century and thinking that it was so funny, the juxtaposition, that it made me want to push more for ways of playing with ways that the present and the past are playing with each other. We were really guided by the sensibilities of the show. [Director] Tommy [Kail] always said that there should be no filter, no wink at the audience. There’s something very immediate about the show and the way that it wants to collapse the distance between Hamilton’s time and our world today, and I felt that in the book, too. Everything that’s in it ought to be primary material of one kind or another. It’s a description of an episode, or it’s a direct quote from a document from the time, or it’s Lin commenting on his own process. Immediacy was a big word.”

On Chapter XVIII: “An Account of Rapping for the Children, Who Will One Day Rap for Themselves”

“This chapter is about the student matinees we arranged at the Public. I talked to some of the teachers who brought high-school students to see the show, and those interviews are some of my favorite things in the book because they give a clear sense of what this is going to mean long after the show is out around the country. Lin and I both think that the greatest impact of the show is going to be on the kids who see it and, in a few years, the kids who perform it for themselves. So we were constantly aware of making a book that would make it easier for those kids to do what they’re gonna do.”

On Chapter XIX: “Did They or Didn’t They? Or, Some Discourse on Affairs”

“Nobody was sure if Alexander Hamilton and Angelica Schuyler had an affair. They wrote incredibly flirty letters back and forth, and it’s one thing to say that is ambiguous in the show. It’s written to be ambiguous in the show, but if you’re an actor, you have to play something. You have to decide, are you playing this as if you’re having an affair with the other person’s character or not?

I thought I would be interested to hear what Lin and Renée [Elise Goldsberry] said about how they play Alexander and Angelica every night. So this chapter is a conversation with the two of them about that.”

On Chapter XXIII: “On the Origin and Persistence of Our National Shame”

“This point in the story is when the company has gone back into rehearsal after the Public, but before Broadway, and they reassembled almost exactly on the day of the shooting in Charleston. It was something they had to reckon with, and ‘One Last Time,’ which is so much about George Washington and his hopes for the country, when Washington is being played by an actor of color, it was a moment to try to reckon with what the show means given what’s happening in the country right now.”

On the Epilogue

“The epilogue was sort of tacked on at the end because we thought that we were done, but then we heard that President Obama was coming back, so we realized we weren’t quite done with the book after all. I was onstage when he talked to the cast. He’s in the book three times, and I do think there’s a way where Hamilton captures some of the energy of the Obama era. To be clear, not in a partisan way. It’s not about red hats or blue hats. It’s just about the way that the outsiders move to the center, and making sure everyone has a chance to have their stories told, and about the power of stories themselves.”