Discovery ChannelÔÇÖs new true-crime series Killing Fields follows an actual ongoing criminal investigation. The network is calling this ÔÇ£real time,ÔÇØ which is not quite accurate, but letÔÇÖs grant that the turnaround is brief and the case itself is still unfolding. ThatÔÇÖs a genuinely unusual format ÔÇö outside of, you know, the news ÔÇö┬áand in such crowded TV times as these, who could begrudge a gimmick? Except Killing Fields is doing what so many other shows in the last ten years seem to be doing, and to its severe detriment: taking a compelling idea and turning it into another damn cop show.

Of all the stories out there, all the investigators, all the unsolved crimes, executive producers Tom Fontana and Barry Levinson have brought us the one that is maybe the most trope-filled of them all:

A retired detective who wants one last shot to close a cold case thatÔÇÖs haunted him for the last 20 years teams up with a muscular but perhaps hotheaded young partner whose own painful past motivates but also tortures him; our retiree is old-fashioned, perturbed by the younger generationÔÇÖs affection for time-wasting technologies, but even he has to admit that advances in forensic science could be the key to solving the case this time around. And, hey, remember that serial killer who was around back then? HeÔÇÖs in prison now, but maybe he was involved somehow? Maybe not. But you know what was involved for sure? The ominous, evidence-destroying swamps here outside Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Just ask any of these interesting witnesses, informants, and various locals, like the woman whoÔÇÖll artfully describe the differences between the scents of decaying human bodies and decaying animals. ItÔÇÖs hard for our graying detective, you see ÔÇö┬ábecause of how much he relates to this victim. He, too, has been lonely. He just wants to give her mother closure. Ponder that as you watch B-roll of the fecund but spooky swamplands. People are innocent until proven guilty, says the text on the screen.

The show indulges in the worst vices of a variety of genres, from the bizarre proclamations weÔÇÖd generally expect from, oh, True DetectiveÔÇÖs true detectives, and the cheesy dun-dun-duuuun┬ámusic you get from crapola newsmagazine murder shows. ThereÔÇÖs the strained ÔÇ£dialogueÔÇØ we see on the first seasons of situational reality shows, where people arenÔÇÖt comfortable yet repeating things for the camera.

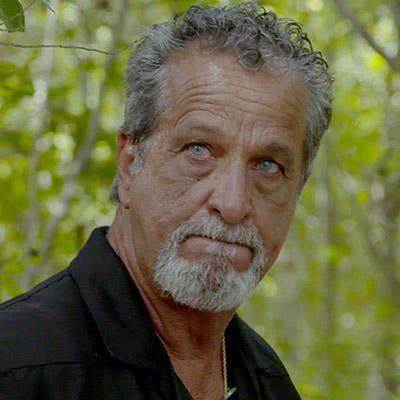

Our main detective is Rodie Sanchez, who decides to come out of retirement because of the murder of Eugenie Boisfontaine, who was killed in 1997. In the first two episodes of the show, its not clear why the case went cold or what investigative strategies were previously exhausted. Sanchez, in one of his many talking-head soliloquies, tells us that Boisfontaine was divorced, and that he has been married six times, so he gets it. She was probably lonely, he says, though its not clear what hes basing that on. The only person that showed her sympathy or kindness  I think was the one that killed her. If he has a reason for thinking that, its never disclosed. In the immediate next scene, he says he has no idea if Boisfontaine was dating anyone at the time of her death  which seems like awfully significant information. Why wasnt that part of the investigation 20 years ago? No one explains this lapse. Sanchez is certainly larger than life, and one can understand the desire to make a show with him at the center, with his frost-white eyes and overintensity. But why this show?

ThereÔÇÖs plenty of true-crime television out there ÔÇö most recently┬áMaking a Murderer, though the shows have very little in common ÔÇö and the genre contains both high art and nasty garbage. We have entire cable networks dedicated┬áto tabloid-oriented crime shows, network newsmagazine hours focused exclusively on tawdry, horrifying tales of murder and violence. Pretending murder doesnÔÇÖt exist is silly and prudish, and thereÔÇÖs no point in denying that we all have a sense of human curiosity about depravity. But thereÔÇÖs a strange thing happening with┬ánonfiction programming right now. It has to contend with not just its own content but its competing format ÔÇö reality TV ÔÇö and with that comes a┬ápackagedness, a confounding irony that reality is synonymous with contrivance.

ThatÔÇÖs tolerable most of the time. This isnÔÇÖt TV court; people donÔÇÖt care that the Real Housewives┬áwouldnÔÇÖt actually be putting on a charity fashion show without Bravo producing one, or that the people on┬áDuck Dynasty┬áare monstrously homophobic. They know the people on┬áTop Model┬ádonÔÇÖt become top models. Even blogs, which once upon a time were this authentic-seeming antidote to the artificiality of other mass media, have trended toward staginess; life is not made of poised Instagram latte-scapes, but oh, that it were. If we all just wanted to watch actual, real life, we could just pull up a chair and stare out the window, or, I donÔÇÖt know, volunteer somewhere?

Killing Fields┬ácertainly didnÔÇÖt create this environment, but it does exist in it, albeit clumsily. Yes, these are real people, but so much of it feels phony. It┬áadapts its moves from scripted dramas, reality television, and tabloid newsmagazine shows ÔÇö genres that distance us from the immediacy of being a human being. Sometimes, in scripted dramas, this is in the pursuit of a grander truth; itÔÇÖs not inherently a bad thing to use context or framing or devices. But Killing Fields also is based on ÔÇö is advertised┬áon, sold on, the whole point of it is that itÔÇÖs a real-deal case thatÔÇÖs legitimately currently being investigated, and itÔÇÖs still being filmed, and no one knows what the outcome will be.┬áSomeone real has actually been murdered, and that part isnÔÇÖt staged, and she had a real life, with real joys and real sorrows, and she has a real mother and a real brother, and she really did die.┬áItÔÇÖs an uncomfortable tension, and on a show that has so much else to solve, itÔÇÖs one issue too many.