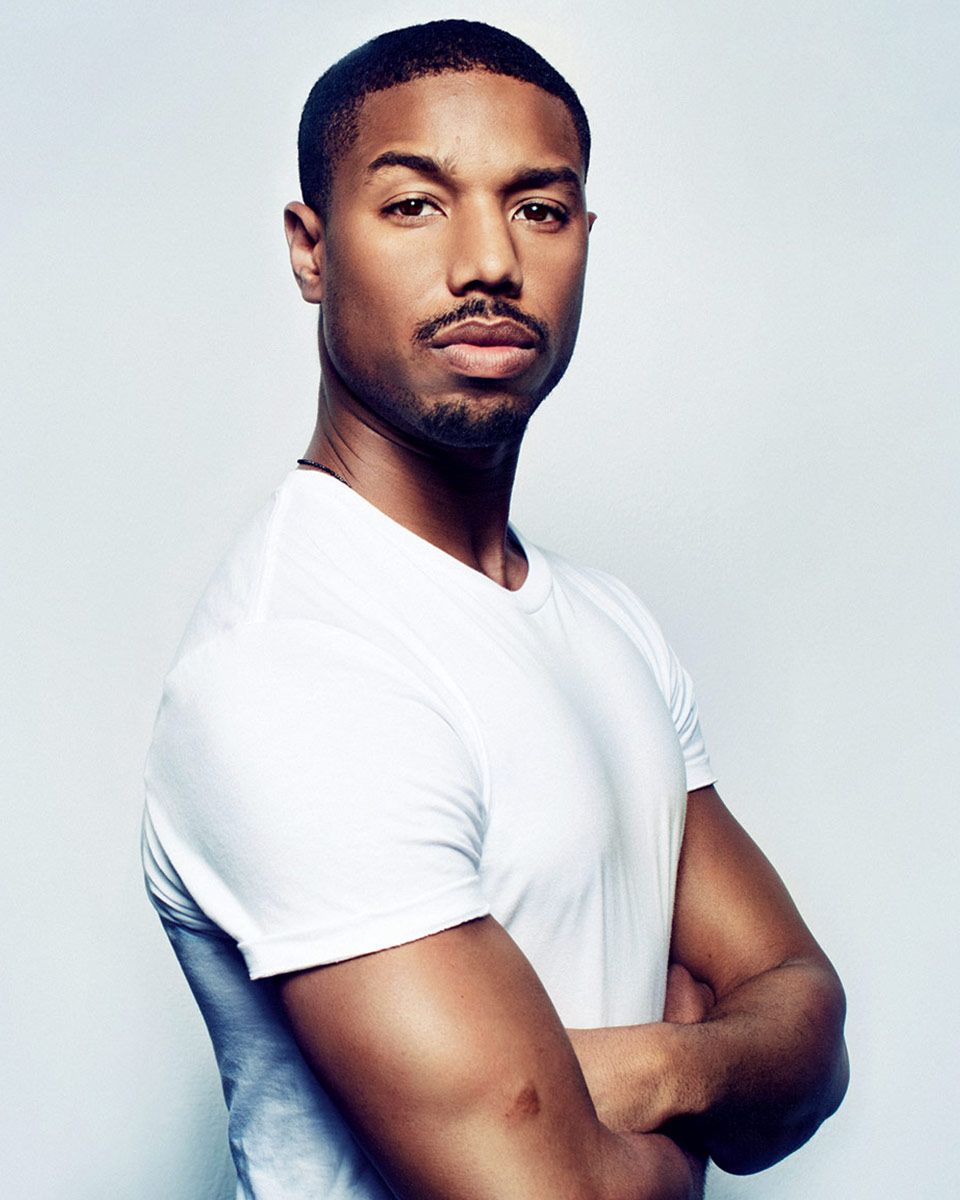

There’s a moment you rarely catch famous people in — right after they blow up, but before they’re too big to remember what it’s like to be normal. It’s the morning of December 23, and nobody should want to be here in this Los Angeles event space talking to a reporter, least of all actor Michael B. Jordan and writer-director Ryan Coogler, both of whom must have better things to do on Christmas Eve eve. But neither seems unhappy; they’re relishing the attention and the opportunity to spend time with each other before the holidays, boyishly clowning around. When someone mentions lunch, Jordan raves about a nearby restaurant’s fried-chicken sandwiches as he shadowboxes in front of a mirror. An inquisitive Coogler asks me about my Jordans, which I ramble about, and then about whether he should see Hamilton, which I ramble even more about. A string of Mary J. Blige songs box-steps through the speakers, followed by Shanice’s “I Love Your Smile.” Coogler and Jordan compliment the playlist while dance-walking through the room.

In other words, it’s easy to forget that I’m talking to two of the hottest commodities in Hollywood, fresh off Creed, the new Rocky sequel directed and co-written by Coogler and starring Jordan as boxer Adonis Creed (son of Apollo), which has grossed more than $100 million since its Thanksgiving-weekend opening, earned a Golden Globe for Sylvester Stallone (who returns as Rocky Balboa, Adonis’s trainer), and revitalized a seemingly maxed-out franchise in a time when revitalizing maxed-out franchises might be the one skill the movie business values most. Things are changing fast for the pair, and their next projects will be whatever they want them to be. A week after our meeting, Coogler will make rumors true by signing up to direct Marvel’s Black Panther movie, and then he’ll actually attenda performance of Hamilton, causing the internet to speculate, based on very little evidence, that he might make Hamilton: The Movie.

At least Coogler still has some anonymity, though. To prepare for Creed, “we went to see Mayweather fight Maidana. Sly hooked it up,” he says, in his thick Bay Area accent. “We were trying to get something to eat. We couldn’t get two steps without somebody stopping Mike. It was mostly women, and they weren’t even asking, they were just handing him the phone. I’m seeing his life change in a way that’s so different from mine as a director. I’m able to get a sandwich when I want to.” Jordan, whose 2016 began with an award for best actor from the National Society of Film Critics, is still adjusting. “You’re thinking about things you would never otherwise think about,” he says. “Before I leave up out the house, I’ve got to think about where I’m going and who might be there. Do I need a haircut today? I haven’t gotten a cut in like a week. Damn, I just wore this shit out — and the paparazzi might be out there. You start to think about things that are not normal.”

Jordan, 28, grew up in Newark, the son of a guidance-counselor mother and a caterer father. He got into acting early, landing his first big role at 14 in 2001’s Hardball, in which Keanu Reeves takes a job coaching a team of black kids from the Chicago projects to repay his gambling debts. After that, a decade of peaks and valleys: Jordan played Wallace on season one of The Wire in 2002, and Vince on Friday Night Lights from 2009 to 2011, with a three-year stint on All My Children in between. Lights led to a part on TV’s Parenthood, which led to ones in George Lucas’s 2012 Tuskegee Airmen movie Red Tails and the found-footage superhero thriller Chronicle that same year. He was up-and-coming but hadn’t yet broken through. And then he met Coogler.

Coogler, 29, grew up in Oakland and Richmond, California. His mother was a community organizer and his father a juvenile-hall probation counselor. He was an athlete and would eventually attend Saint Mary’s College of California on a football scholarship, but he always knew there was another side to him. “The other day, I asked my fiancée, who’s known me since I was 13, ‘Were we jocks?’” says Coogler. “And she was like, ‘I was, but I’m not sure what you were.’ Because I also had friends that were full-fledged thugging and had kicked sports to the curb, but then I also liked comic books and movies.” An English professor at Saint Mary’s encouraged him to try screenwriting, and he went on to USC film school, where he made a series of award-winning short films.

While Coogler was finishing up at USC and starting work on Fruitvale, his father was diagnosed with a rare neuromuscular condition. “He was battling health issues my whole life, but this one was crazy — his muscles were atrophying,” says Coogler. “I knew my dad when he was young and strong and tough. He was a big Rocky fan, so growing up I would watch the movies on TV with him, and he would always cry.” He’s told some version of this same story a number of times over the past few weeks, but from the way he crouched over to explain, I got the sense that it still isn’t easy. “When my dad was 9, his mother was diagnosed with breast cancer. They would watch TV together, and at the time, Rocky IIwas always on. So watching Rocky movies with me, he would be reacting to the movies, but also to memories of his mom. Our relationship had changed so much, and now I got to take care of him. So I came up with this idea of something similar happening to his hero, and that’s how I came up with the idea for Creed.” (In Creed, Stallone’s Rocky is diagnosed with non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma.)

Thankfully, Coogler’s father has recovered. “This Thanksgiving was weird, bro,” Coogler says, smiling. “It was great, but also different, know what I’m saying? My family lives in the Bay Area, and everybody wanted to go see the movie. After dinner we all hopped in the whips and went to the theater right there in Richmond, bought hella tickets. And my dad — I told you, a big Rocky fan — had made Creed shirts. So everybody wore the Creed shirts that he’d designed.”

Jordan’s parents are equally proud, which I know because I’ve met them. In early November, Jordan was doing press for the movie in Philadelphia, Rocky’s hometown, where seemingly every telephone pole downtown was adorned with a banner with Jordan’s face on it. By chance, I happened to be attending a conference in the same hotel where a Creed junket was taking place. Jordan’s manager saw me tweet something about Philadelphia, texted me about my plans, and invited me to come say an off-the-record hello during Jordan’s lunch break. In his hotel room, Jordan was on the couch watching college football while his parents sat nearby eating room service. I was intruding on his downtime, but he acted happy enough to see me. His parents, though, seemed thrilled that I’d come by, looking on like they were watching a play-date. Ten minutes later, I left, but not without a hug from Mrs. Jordan.

THE COOGLER-JORDAN OEUVRE SO FAR

Next up, Jordan will star in Short Term 12 director Destin Cretton’s Just Mercy, based on Bryan Stevenson’s 2014 memoir, as a civil-rights lawyer fighting to free a death-row prisoner. After that, he plans to reteam with Coogler for Wrong Answer, the true story of an Atlanta schoolteacher ensnared in a standardized-test cheating scandal. Somewhere between those and Coogler’s Black Panther, the duo will presumably make time for Creed 2, which Stallone has hinted may include Godfather II–esque flashbacks to the relationship between Rocky and Apollo.

But as excited as Jordan and Coogler are to enter the world of franchise filmmaking, they seem even more excited to use their new clout to make the types of movies they don’t see in theaters right now. Both are tired of only traditional civil-rights-era biopics. “You got to tell stories in today, or in the future,” says Jordan. “Or can we go back even further? There’s always one period that people want to go back to, but can we go back to Hannibal? Or Mansa Musa, destroying economies as he traveled? Can we go back to the Egyptians?”

The tone isn’t starry-eyed or naïve but more, wait, let’s make a movie about Hannibal, why not? They’re clearly just beginning to come to grips with what they’ve created for themselves, and what it could mean for the future. They’re still humble, but also brash in a way that is infectious. “I used to get crushed when I was younger and would watch movies about young people,” says Coogler. “And I’d be like, No — that’s not us. Or reading articles about the millennial generation — people making general statements about us. Again, no. Wrong. Just hire us, bruh. Hire me and let me work.” Says Jordan: “The majority of roles out there are written not by us” — meaning young black people — “so if [most writers’] only interaction with someone who looks like me is from stereotypes, what you see on TV, then those are the types of roles that are going to keep getting written. Also, I don’t have to go out for every role that’s written black. I want to go out for the role that’s written [with race unspecified] — I’m going to make that role black regardless.” They’re excited to change preconceived notions about black film, while not abandoning the idea of being blacks in film. “Black art, it’s so complicated. Because there is no white art,” Coogler said. “Because, whether people want to admit it or not, you know, in this country, in this culture, white is seen as the norm. Because there’s no need to identify it as anything, it’s looked at as standard. Which, if you compare and contrast that, there’s an inherent unfairness to it.”

You can see the beginnings of a Scorsese-DiCaprio-style alliance, with Coogler casting Jordan in complex, multidimensional parts, and Jordan providing the star power to get their movies green-lit. But for right now, they’re happy to be their own two-member support group. “There are emotional highs and lows, so it feels good to be able to talk,” says Jordan, who lives in L.A. but regularly calls Coogler in the Bay Area. “Just to pick up the phone when you’re stressed or worried about a decision: ‘Yo man, how you feeling? Damn, aight, cool. I just needed to say that out loud.’ Hearing from someone who understands, and hearing him say what you’ve been thinking, it’s like, Great, I’m not completely insane. Which makes this easier.”

*A version of this article appears in the January 11, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.