Graphic novelist Tom Hart and his wife, Leela, lived through a horror story. Their baby girl, Rosalie, beautiful and vibrant, like all little children, died unexpectedly ÔÇö and without explanation ÔÇö in 2011, three weeks before her second birthday. ItÔÇÖs the kind of thing often too painful to consider, let alone experience. But Hart, the acclaimed author of the Hutch Owen series of graphic novels, wasnÔÇÖt given a choice, nor did he have any option but to try to arrive at some sort of understanding ÔÇö tenuous as it may be ÔÇö by turning what happened into art. ÔÇ£There was a part of me,ÔÇØ says the soft-spoken, Gainesville-based Hart, ÔÇ£that realized I need to give my feelings some sort of form.ÔÇØ┬á

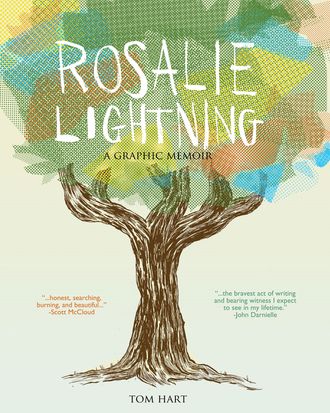

The form of which Hart spoke became, ultimately, his new work,┬áRosalie Lightning: A Graphic Memoir. The book recounts RosalieÔÇÖs life and death, and their immediate aftermath. I know itÔÇÖs only January, but IÔÇÖm hard-pressed to imagine coming across a more emotionally honest and moving piece of art this year. ItÔÇÖs the kind of book thatÔÇÖs simultaneously almost too painful to read and yet impossible to put down.

Shortly before the New Year, Hart talked through, as best as he could, the process of putting the unthinkable down on paper.

After the initial shock of what happened to Rosalie, I was doing a lot of scribbling and note-taking, just to put my thoughts someplace. I have a long history of dealing with my emotional state by turning it into characters and situations and form. So, even in the first couple days after she died, when I was capable of having a thought, I felt that, to get some sort of understanding, IÔÇÖd have to put everything into book form. But, you know, you quickly realize that you never ÔÇ£understandÔÇØ what happened. Instead of understanding, or something as trite as ÔÇ£moving past it,ÔÇØ the best you can do, I think, is integrate the facts of what happened into your life ÔÇö stop trying to deny it, or stop suffering from it.

Once I got to the place where I was ready to focus on making the book, there was the challenge of figuring out how to convey what happened in a truthful way. It can feel very strange to look at something so personal in terms of narrative artificiality and structure. But I never really questioned whether or not putting what happened to Rosalie into a particular form was in any sense bending what happened to my artistic will in a wrongful way. I felt strongly, actually, that it was the right thing to do. ThatÔÇÖs not to say I wasnÔÇÖt sensitive to the idea of omitting something or including too much. There were some things that were just too painful. The most significant example might be early on in the book, after the paramedics came to our place when Rosalie was unresponsive. I barely touched on being in the hospital with her. It was unbearably horrible. I was starting to sit down and write it out and draw it out, and I realized I couldnÔÇÖt do it. There was enough horrific material in there already.

This might sound hard to believe, but I was pretty concerned about not wanting to make a heart-wrenching book. I just wanted to make an honest book, you know? I also didnÔÇÖt want to make something that read like horror. I wanted to describe. ThatÔÇÖs it. I think that worked for me. I donÔÇÖt know. Certainly as a person and not as an artist. People talk about art as being cathartic. I donÔÇÖt know if it always is; if the definition of catharsis is about letting go. I donÔÇÖt know the exact meaning of the word. I think the word I used before, integration, is a good one. I needed to integrate the experience because there was so much of me that couldnÔÇÖt believe it and was shocked by it that I think making a project out of it sort of allowed me to deepen the belief that it did happen. In that way, working on Rosalie Lightning did lighten things. Maybe. But cathartic? Drawing her was really a kind of beautiful experience, and heartbreaking, but I felt that she could still be there a little bit if I put her on the page. It was healing. I can say that.

I donÔÇÖt think you can underestimate how healing art can be. ThatÔÇÖs maybe another part of why I wanted to write the book, though I didnÔÇÖt know it at the time. One of the first things I remember doing after Rosalie died was emailing friends who were very encyclopedic about art and literature and movies, and asking them to send me things to watch or read or listen to. I didnÔÇÖt get very many responses, when what I wanted was just to gorge on art that might give me some meaning. So I was aware that putting my book into the world might be beneficial to other people who have gone through a similar experience. But what really became clear to me was that your experience starts to shape everything and be reflected everywhere. I put it in the book ÔÇö a line from a song or some strange Kurosawa movie will feel like theyÔÇÖre speaking directly to you. ThereÔÇÖs also the epigraph in the book, by Ben Lerner, that sort of sums it up: ÔÇ£There are no non sequiturs when youÔÇÖre in love.ÔÇØ There arenÔÇÖt any when youÔÇÖre in a certain kind of pain either. Everything makes an awful kind of sense.

To some degree, the book is maybe my attempt to test the theory that art can get us through life. IÔÇÖve often exalted art over a lot else in the world. ThereÔÇÖs probably some version of me that at 14 years old couldÔÇÖve gone down a path that led to becoming a political activist of some kind, but I didnÔÇÖt. I chose to make my life about art. I donÔÇÖt know why. If IÔÇÖm honest, there wasnÔÇÖt a rich culture around me when I grew up, so I was looking for answers to how to behave, and I saw it in art. I mean: Peanuts. At age 7 I saw that, and thereÔÇÖs always some punching and hitting and kicking, and I think I learned to navigate the realm of high emotion starting with Peanuts.┬áYou know, thereÔÇÖs a book called ManÔÇÖs Rage for Chaos┬áthat argues the theory that art is not a place where we make life seem orderly and comprehensible, which is what a lot of people say, but in fact, art is a place where we give ourselves the opportunity to experience chaos and extreme experiences. I think thereÔÇÖs something to that.

A close friend of mine committed suicide not that long ago. IÔÇÖve thought about it a lot. At least right now IÔÇÖve come to see death as something that happens, and the living just gotta keep going. ThereÔÇÖs a couple of friends who are really, really saddened by that particular death, and IÔÇÖve thought of giving them a copy of Rosalie and just saying, ÔÇ£Hey, hereÔÇÖs what I wrote, hereÔÇÖs what I did when Rosalie died, and maybe youÔÇÖll get something out of it.ÔÇØ I think thatÔÇÖs as expressive as IÔÇÖm capable of being right now.

I dont know what Ive learned from this whole experience. Sometimes I feel that Im a little calloused. But the short answer  I dont know. The line in the book, The body is a metaphor for the soul  in my healthy adult life, Ive believed that were not our bodies, and it doesnt really matter what happens to them. The body is just a reflection of what the consciousness is doing. Does that make any sense? Maybe not.

I do wonder what Molly Rose will think about the book. I want her to know the story of her sister. I think when sheÔÇÖs old enough to be interested in Rosalie Lightning, sheÔÇÖll get it. I think sheÔÇÖs going to be a pretty smart kid.