This month Vulture will be publishing our critics’ year-end lists. Last week’s lists included albums, art, and video games. This week we’ve covered comedy — sketches, specials, and podcasts — plus Margaret Lyons’s top shows, Bilge Ebiri’s top movies, and music videos and memes. Now it’s on to late-night clips, comic books, graphic novels, and album reissues.

One of the signs that a medium is in a healthy state is when it can produce a crop of great work from both veterans and upstarts. By that measure, it’s a good time to be reading English-language graphic novels. This year brought masterful books from beloved titans who made their bones decades ago, but it also brought wonderful material from young talents who are transcending their roots in web comics and crowdfunded self-publishing. It was also a good year for genre storytelling: Although there was terrific work in the memoir and realist veins, some of the best stuff was steeped in fantasy, action, and stylized quirkiness.

A note on methodology for the detail-oriented: We’re using the unendingly debated term graphic novel here loosely, choosing to use it as shorthand for book-length pieces of sequential art that were not initially released as monthly printed comics. There’s a separate top-ten list for the year’s best monthly comics series.

1. Step Aside, Pops by Kate Beaton (Drawn and Quarterly)

Kate Beaton’s work isn’t challenging, per se. As anyone who has fallen down the rabbit hole of reading her hundreds upon hundreds of web comics can tell you, it’s easy to gobble up her strips without scratching your head about any of them. The vast majority of her work is light, hilarious, and endearing. So what is her latest collection of work doing on a list that’s otherwise populated by dense, weighty tomes? It’s the same reason Lucille Ball, Mel Brooks, and Charles Schultz are creative icons: Funny doesn’t come easy. Beaton is the leading light of North American cartooning right now, a human wellspring of laugh-out-loud punch lines with a fantastic visual and verbal lexicon that is wholly her own. Step Aside, Pops has everything that has made her an emerging titan: arch-but-humane reimaginings of history and literature, progressive commentary that’s as observant as it is goofy, formally innovative riffs on antique book covers, gags about pigeons — it’s all here, along with insightful author commentary on each set of strips. It’ll be fascinating to see where she goes, but for now, it’s just a privilege to spend time in the world she’s making.

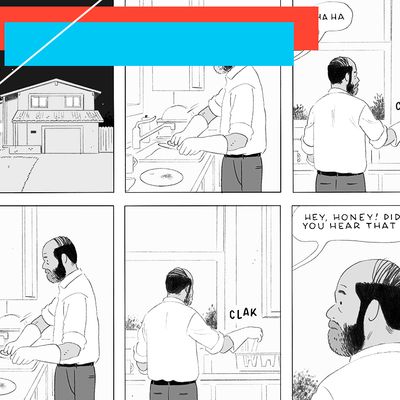

2. Killing and Dying by Adrian Tomine (Drawn and Quarterly)

Ho-hum, another masterpiece from Adrian Tomine. It’s been a few years since we got a book-length work from this venerable master of the medium, but this collection of short stories reminds us that his unique talents have in no way faded with age. Indeed, he’s growing as a visual storyteller: “Intruders” has him breaking from the smooth-textured style he’s famous for; “Translated From the Japanese” is more like an illuminated manuscript than a comic; and the title story conveys dialogue and sound effects in bold new ways. But never mind all that formal stuff: The centerpieces, as always, are his well-observed plots and struggling characters. No one uses minimalism to grab your heart quite like Tomine.

3. SuperMutant Magic Academy by Jillian Tamaki (Drawn and Quarterly)

There was a time when full-page comic strips were the dominant form of American sequential art, but they’ve been in steep decline for decades. Thankfully, we have the brilliant mind and pen of Jillian Tamaki to revive it to awe-inspiring effect. SuperMutant Magic Academy is a series of strips about a school that’s part Hogwarts and part Xavier’s School for Gifted Youngsters, but nothing about it feels like stale parody. The lockstep rhythm of charming setups and surreal punch lines aggregates into a lengthy, funny work about growth and confusion.

4. The Sculptor by Scott McCloud (First Second)

Who could’ve seen this coming? It’s been 22 years since McCloud published Understanding Comics, his unparalleled treatise on the visual science of sequential art — and up until this year, it looked like explanatory nonfiction would forever be his primary legacy. Then, out of nowhere, he puts out a phonebook-size epic of magical realism. Not only is it visually stunning, it’s also constantly surprising: What begins as a Faustian morality play abruptly overturns your plot expectations and uses strange narrative back-alleys to arrive at a breathtaking climax.

5. Nimona by Noelle Stevenson (HarperTeen)

If you’re a coldhearted cynic like me, you’ll have your doubts about Nimona’s first ten to 15 pages. It starts out seeming like a hackneyed story about a quirky gal forcing a stuffy old man to lighten up. But ever so gradually, we learn the story is not at all what it appears to be. Stevenson is one of the best young cartoonists working today, and she proves her mettle with this sword-and-sorcery-and-sci-fi tale. I’ll spoil nothing about the surprising plot, but suffice it to say, it’s rare to see such cute-looking characters go through such thrilling tragedy.

6. Chicago by Glenn Head (Fantagraphics)

This quasi-memoir is so straightforward and digestible that you might not even notice how subversive it is. The history of sequential art is littered with autobiographical stories about impetuous and misunderstood young men on journeys of self-discovery, but Chicago is a subtle dismantling of that overdone subgenre. The protagonist certainly thinks he’s searching for authenticity and inspiration, but Head crafts him as an infuriating narcissist who squanders every opportunity and alienates every friend. Luckily, since Head is (mostly) talking about himself, it remains grounded in a humanely sympathetic tone of grudging self-acceptance.

7. Black River by Josh Simmons (Fantagraphics)

Postapocalyptic storytelling isn’t exactly in short supply for any medium these days, but Josh Simmons does it so damn well that you’ll instantly forgive him for picking a well-worn concept. Black River follows a troupe of exhausted women as they wander through unnamed swaths of North America long after an unexplained armageddon, and it’s unforgettably brutal. The vignettes — a frigid orgy, a set from a calmly insane stand-up comic, an underwater hallucination — are as visceral as they are eerie. There’s a regrettable detour into sexual violence, but it’s thankfully short and more than overshadowed by the rest of the gripping, hopeless narrative.

8. Wuvable Oaf by Ed Luce (Fantagraphics)

It’s tempting to think of Wuvable Oaf as a kind of queer Scott Pilgrim, filled with kitsch references, visual stylization, and rock ’n’ roll. But Luce’s hefty tome starring a hefty man is a unique beast. Emphasis on beast, as it’s a series of scenes centered about Oaf, a lovable and hairy dude whose physical strength is as massive as his appetite for romance and Morrissey lyrics. The book is formally inventive and heartfelt, reading like a mid-century romance comic steeped in the lewd sexual fantasies of classic underground comix. But the most admirable aspect is the indelible characterization of Oaf himself, a bear you’ll never forget.

9. Virgil by Steve Orlando, Chris Beckett, and J.D. Faith (Image)

Orlando is a relatively new talent in comics, but he’s already proving to be one of the industry’s best writers for beat-’em-up storytelling. He also happens to be bisexual and has made the wise decision to carve out a niche: kickass action starring queer leads. This “queersploitation” (his word, not mine!) epic follows a closeted Jamaican police officer seeking vengeance against the homophobic cops who attacked his boyfriend, prompting a visually sumptuous odyssey through the grim streets of Kingston. Although there are vivid moments of heartbreak and bigotry, Virgil isn’t a polemic — it’s a rip-roaring revenge ride of the highest order.

10. Displacement by Lucy Knisley (Fantagraphics)

Finding new ways to tell an autobiographical comics story is tough. But acting as sole caretaker for your nonagenarian grandparents on a cruise ship is infinitely tougher. In her fourth book, Lucy Knisley deftly conveys the frustration of managing her ailing “grands” during a maritime excursion, inducing pangs of recognition in any reader who’s been around the decaying bodies and psyches of loved ones. What really sets the book apart, however, is Knisley’s sparing artwork: Her unhurried lines and gentle watercolors create a show-don’t-tell buffet of melancholy.