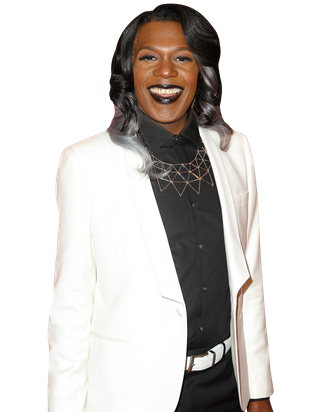

Beyoncé may lead the formation in her latest world-stopping event, the surprise release of “Formation” one day before she performed it at the Super Bowl, but she isn’t the only southern queen whose voice you’ll hear on the song. She’s joined by New Orleans’s Queen of Bounce, Big Freedia, who arrives midway through the song to reinforce Bey’s hot-sauce-carrying swag with some slay-spo of her own:

“I did not come to play with you hos! I came to slay, bitch! I like corn breads and collard greens, bitch. Oh yas, you besta believe it.”

It’s words to live by and, according to Freedia, the code of the Crescent City. Vulture spoke with Freedia after a whirlwind week at Mardis Gras about what it really means to slay, Beyoncé’s southern roots, and why it’s a waste of time to protest Queen B.

Were people shouting your “Formation” verse at you all through Mardis Gras?

Oh my Gooood — “Formation!” “I came to slay!” — they would say all kinds of stuff. It was crazy, like I might need a bodyguard. I was trying to be chilling, relaxing — but it wasn’t working. But I had fun.

Did you know the song and video were dropping the day before the Super Bowl?

Not exactly that day, but when we spoke, I knew it was coming out within the next two or three days. I was like oh my God when I saw it. I couldn’t believe it. How I found out was my phone blew up; that’s how I knew it was out. I had been asleep, and then I woke up to everyone saying, “Congratulations, I heard you on that song!” So of course I went to immediately find it. I was just shocked. I’m still shocked.

Any favorite moments from the video?

Well, of course the line about having hot sauce in my bag. Red Lobster — there are so many things that stuck out. It’s such a phenomenal video, which is normal for Beyoncé. She puts out phenomenal pieces, and she worked really hard. That’s why she’s the Queen B.

There’s a piece on Slate — as well as others by black women from New Orleans — that argues Beyoncé appropriates New Orleans’s collective trauma post-Katrina in the video. Did her intentions behind the song and video feel genuine to you?

Oh yes. You know, being the artist and not knowing when you sometimes create a song, you don’t think about whether it’s gonna start controversy or whatever. Sometimes you just write and you’re in the zone. But I think with this song, once they wrote it and got everything together, the director [Melina Matsoukas] decided on some things they were gonna put in it. Because of course they had a concept for it. And I think they just thought: We’re gonna do this, and we’re gonna get our message across. Beyoncé has a platform; what’s a better way to speak on your platform than through your music? Some issues just need to be dealt with — that we’re still dealing with in the world, with police brutality and racism. I’m glad she spoke out on it.

You don’t feel like she misrepresented or exploited the city?

No, not at all. And she’s not even that far from here; her family is from New Iberia. So it’s all down south and a part of Louisiana.

What do you think about people protesting now? There’s even an anti-Beyoncé rally planned for outside the NFL’s New York City headquarters [Ed. note: Only three people actually showed up to protest Beyoncé, while the BeyHive swarmed it]. Some people think the video and Super Bowl performance are anti-police.

When we see police, we get frightened because we don’t know what the situation may turn out to be. We don’t know if we’re gonna get locked up, if they’re gonna beat us, we don’t know. These protesters are wasting their time, and it’s bullshit that they’re gonna do an anti-Beyoncé rally over this here. Do something more creative for the world; do something more creative for New York. Shit.

How did it feel to hear Messy Mya, another New Orleans bounce queen whom Beyoncé samples, on the song with you?

That was awesome — another person repping New Orleans and bounce-music culture. It’s unfortunate that we lost him to violence, but it was an amazing feeling to have him open this Beyoncé song.

Did you know him before he was killed?

Yes, I did. He looked up to me. He was just starting — he was more of a comedian and then became a bounce rapper. So he kind of did something that none of us did. He was just what his name said: Messy Mya — he would look at you and read anybody, no matter who it was, a grandma or grandpa, whatever. And we lost him to whatever nonsense [led to his murder]; it was nonsense that he got killed over, and very unfortunate for the city of New Orleans.

Where did you get the inspiration for your verse?

Well, they said, “Give us some New Orleans.” [Laughs.]

What does slaying mean to you personally?

It’s an attitude that represents that city [New Orleans] in a word. Flavor, fever, and fears.

In your memoir, you told so many beautiful stories about New Orleans, including what happened to you and your family during Hurricane Katrina. Do you plan to write more about your life?

Yes, but it’ll be a cookbook. I’m a beast in the kitchen. [Laughs.] And then I have a few things that I’m considering — you know, I wanted to do a kids’ book. So depending on which one publishers like, that’s what I’ll be putting out.