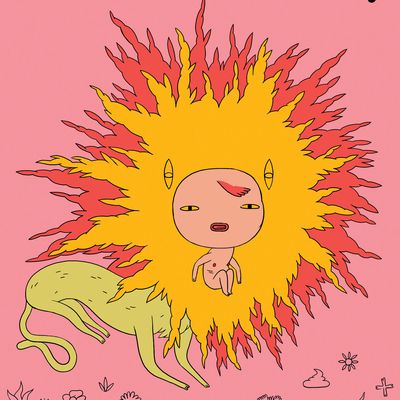

In the world of comics, thereÔÇÖs no shortage of narratives about adolescence. But youÔÇÖve probably never read one as memorably surreal as Michael DeForgeÔÇÖs Big Kids. DeForge is one of the most inventive and prolific cartoonists working today, producing pieces in the form of book-length narratives or short pieces compiled in his periodic series Lose. His work runs a bizarre gamut, from invented biographies of hideously deformed Canadian monarchs to the tender inner monologue of a misshapen bird.

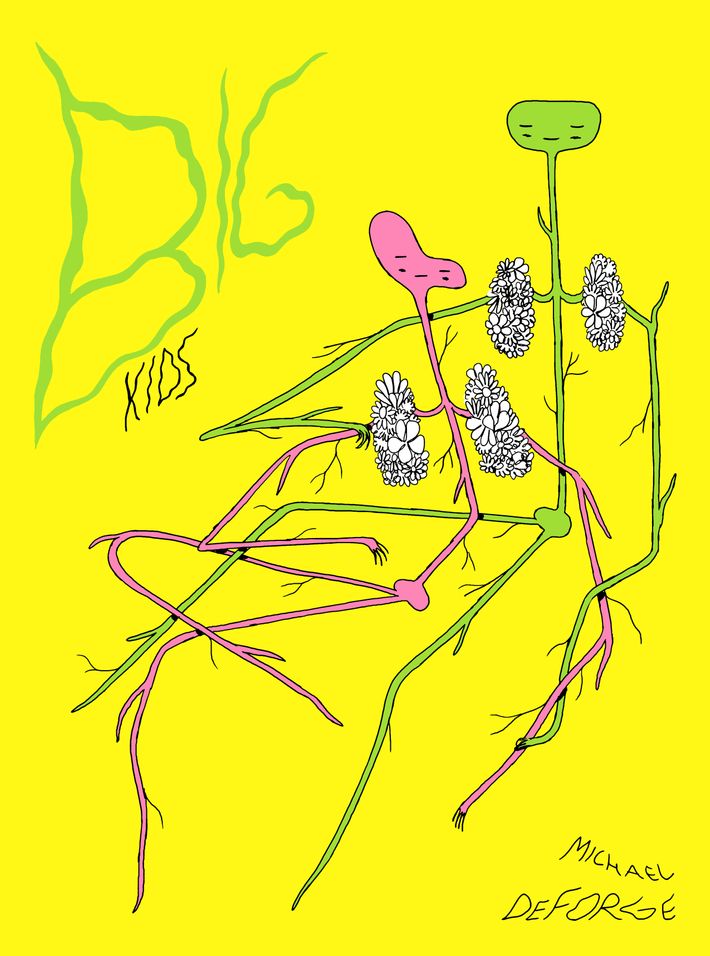

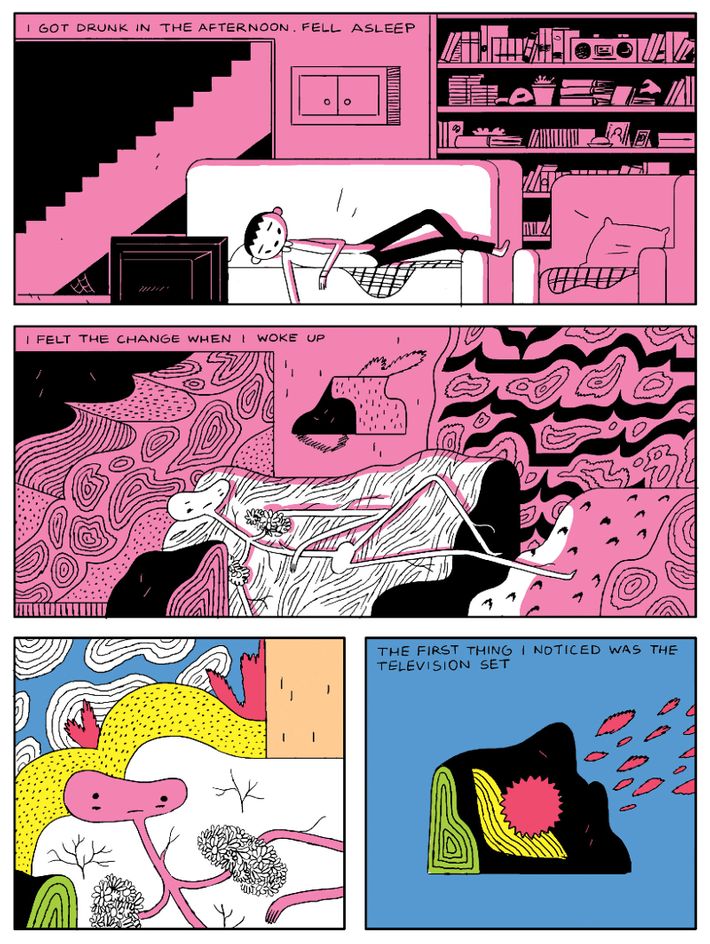

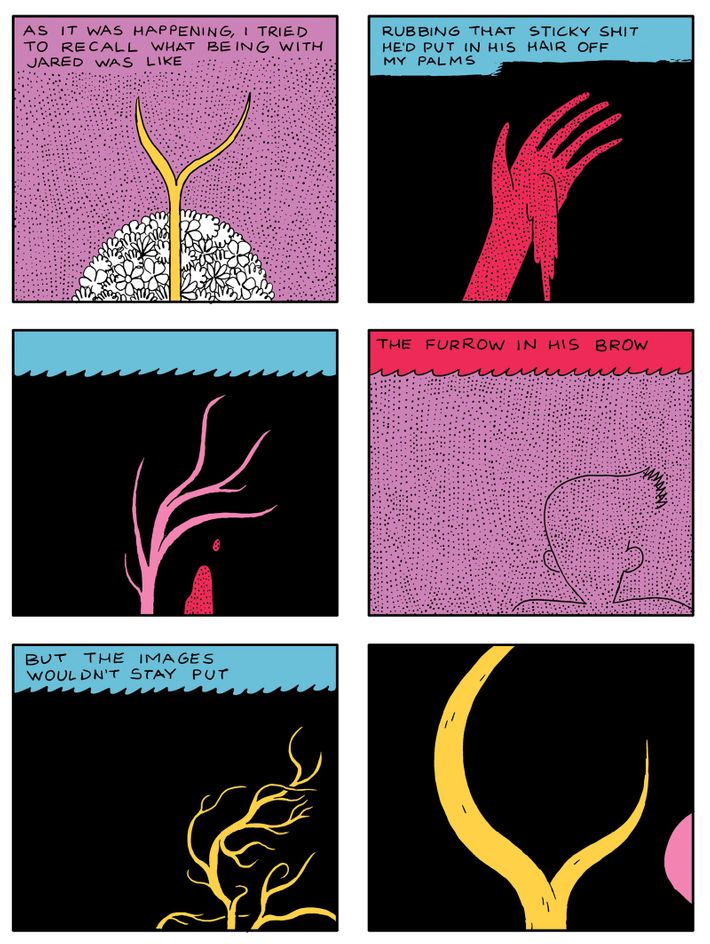

Big Kids is a small book ÔÇö only a few inches in width and height ÔÇö but it packs a punch. It follows the tribulations of a teenager who one day finds himself transformed into a spindly, branch-shaped structure. He soon learns heÔÇÖs become something called a ÔÇ£treeÔÇØ (which isnÔÇÖt exactly the same as a root-and-branch tree), and that heÔÇÖs not alone in his transformation. The ensuing story is alternatingly wistful and stomach-churning, and DeForgeÔÇÖs deceptively simple line-work gives the whole tale a dreamlike quality. We caught up with DeForge to talk about bad adolescences, his work as a designer on the hit cartoon Adventure Time, and the time he worked at a porn shop.

Big Kids stars an anxious kid. What makes you anxious?

Everything makes me anxious. I realize IÔÇÖm anxious for no reason or reasons I canÔÇÖt always control, but yeah, I was an anxious kid. Now IÔÇÖm an anxious adult. Even when my comics arenÔÇÖt overtly about that, they do depict a world that has a very nervous, hostile energy to it, because I think that is still the way I entered the world. I feel like thereÔÇÖs a buzzing hostility underneath the surface of everything, even though I know rationally thatÔÇÖs not actually the case.

What kinds of comics did you read when you were a kid?

My parents had a lot of collections lying around. They had a lot of Bloom County, Calvin & Hobbes, Far Side, and Peanuts collections. As a kid, I was always interested in those. Then my dad also used to read superhero comics, so he had a lot of those lying around as well, and that was something I became interested in throughout my adolescence. I basically learned to read through those collections lying around, so it became a thing that stuck with me.

And when did you start making comics, yourself?

IÔÇÖve always been working on them. As a kid, IÔÇÖd always have these false starts with comics and throughout high school ÔÇö

Wait, what do you mean by ÔÇ£false startsÔÇØ?

IÔÇÖd have some very ambitious idea, and then IÔÇÖd only draw three pages of it and then move on to the next idea, which I think is pretty common as a kid, where you spend a long time designing characters or coming up with ideas that you never follow through on. Then in high school, I started making zines. I just kept working on it, and all those experiments and false starts and small projects culminated into Lose No. 1 eventually.

What were you doing for money in the early period of your comics work?

I was just working odd jobs. I was dishwashing a lot. I worked in a lot of kitchens, warehouses, telemarketing, worked in a porn store once ÔÇö just, like, anyone who would pay me. I dropped out of college, and then I just bummed around for a little while. Working on comics at night and then any odd job that would pay me during the day.

A porn store! Any useful lessons learned there?

I donÔÇÖt think anything useful. It was certainly an interesting type of clientele. It was specifically people who, for whatever reason, couldnÔÇÖt access porn at home, and they used the booths. I donÔÇÖt think I picked up anything very useful. It was not one of the cool, progressive sex shops. It was a scuzzy, piece-of-crap place.

At what point did you unclench and say, ÔÇ£Okay, IÔÇÖm someone who makes comics and thatÔÇÖs a sustainable thing for meÔÇØ?

It just worked out in bits and pieces. IÔÇÖd always been doing some freelance illustration on the side, so for a while I was hacking it out that way. I did have a stretch where I was able to stop dishwashing and just do the freelance work. For probably about a year, I was coasting with that. Then it wasnÔÇÖt until Adventure Time hired me that I stabilized, and thatÔÇÖs been my steady gig for a few years now. ItÔÇÖs a job I like, but itÔÇÖs also nice to know IÔÇÖm not constantly in danger of having to go wash dishes again.

What are your daily tasks for Adventure Time?

IÔÇÖm officially the props and effects designer, so I mostly draw coffee mugs and swords and stuff. Like lightning bolts and things like that. IÔÇÖve done a lot of odd jobs for the show ÔÇö like, IÔÇÖve done concept art and co-storyboarded an episode.

I hope this isnÔÇÖt too personal, but youÔÇÖve mentioned in your comics that you were hospitalized for mental-health reasons a little while back. Once you got out, how important was your comics work during your re-acclimation to daily life?

It was very important. It became, for a while, the only thing I felt I could rely on. I guess I was struggling with other things in my life, and I felt like I had a hard time relying on my body or the chemistry in my brain or my friends, as these things happen when things get out of control. You feel like you canÔÇÖt really trust yourself or people around you. Artwork became the thing I felt like I could rely on.

How did that trauma influence your work, if at all?

The big thing was that I came to it with a deeper focus, maybe. Like, Okay. IÔÇÖm going to stop just noodling around. I want to actually finish comics on a regular basis. I donÔÇÖt want to just keep doing these experiments that donÔÇÖt really go anywhere. I was really deciding to throw myself into sustained narratives, more ambitious projects, things like that.

Speaking of sustained narratives: What was the origin of Big Kids?

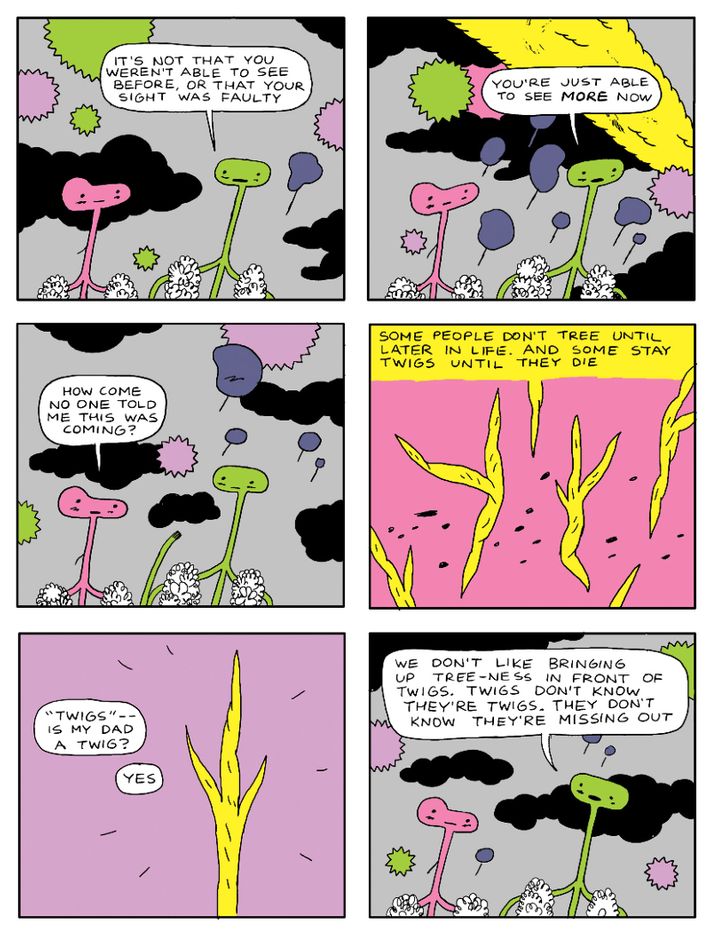

I wanted it to be a coming-of-age story. I think, originally, it was more of an idea that the trees in the book were like a secret society rather than like a mental and physical maturation. It was a secret, hidden, underground society somebody becomes privy to. Then as I wrote it, the secret-society aspect I just abandoned. It became much more about seeing the world in a different way.

The book is probably the longest use of a motif you use a lot in your work, which is physical transformation. What is it about transforming bodies that appeals to you so much?

ItÔÇÖs something I think about often. I write a lot about times in peoplesÔÇÖ lives where you feel like you arenÔÇÖt in control of your body or you start to realize thereÔÇÖs a pretty harsh separation between your body or the chemistry of your brain and your self. You donÔÇÖt have agency over it. I like writing about transformation because I find it something that can be both exciting and empowering and then also very frightening in the same breath. Adolescence is full of all of those transformations, which is the allegory in Big Kids.

On a scale of one to total hell, how bad was your adolescence?

It was pretty rough. I think itÔÇÖs pretty rough for everybody. ItÔÇÖs a really crappy time to be a person.

How important is doodling in your creative process?

ItÔÇÖs very important. A lot of my ideas just come out of just hashing stuff out in a sketchbook. I work in a sketchbook a lot, and it tends to be the default thing. If IÔÇÖm just in a bar or getting dinner or something, IÔÇÖm usually just hacking away at something. I tend to find a lot of my ideas come out of that and by accident. IÔÇÖll draw something and realize, Oh. This might be something I want to explore later on. IÔÇÖll get asked questions about design and where my choices come from, and itÔÇÖs always hard to explain because the answer is always, ÔÇ£Yeah, just kind of made sense in the moment.ÔÇØ Like, it just looked right. I can never tell how I actually got there.

Do you ever get sick of what youÔÇÖre doing while youÔÇÖre in the middle of a story?

Oh, yeah. This is probably also a reason why IÔÇÖm attracted to transformations in comics. IÔÇÖm the type who gets sick of drawing the same character over and over. At some point, I just feel like IÔÇÖve been drawing the arc of a nose 300 times already. I donÔÇÖt want to again. There was a comic I was drawing where I got so sick of the characterÔÇÖs haircut that I just made him shave his head in the middle of it, just so I could draw a different shape for a little while.

A lot of your stories, including Big Kids, lack traditional endings. The narratives often seem to almost cut off mid-sentence. What do you have against endings?

I donÔÇÖt like endings that feel like theyÔÇÖre very punctuated. Real life doesnÔÇÖt have very clean resolutions, and I like the idea that my stories feel like you are just getting a little snippet of someoneÔÇÖs life. I want you to feel like the characters have had some sort of arc, like they realized something about the world or something about themselves has changed in some way at the end of it. I like the idea of it feeling that you drift in on their life, and then you drift out of it.

This interview has been edited and condensed.