Through heavy walls and a warren of hallways, before I’m even buzzed into the studio, I recognize Audra McDonald’s voice. She’s just doing vocalise: singing scales on the syllables eh and oo, nine notes up and eight back down, then again a semitone higher, over and over, up through her range. But it might as well be Puccini. Even performing a rote exercise, she’s an emotion machine.

Inside, her teacher of 20 years, Arthur Levy, is listening attentively, as still as an ornithologist. He stares at her, observing the details of her breathing, which are obvious even through the chunky oatmeal-colored shawl-sweater she’s wearing this raw February night. McDonald, who calls herself a tomboy, is in jeans and boots, her hair piled high in two topiary balls. With her slight defensive crouch and wide stance, she looks like a shot-putter about to let something heavy fly. But she quails as she moves from her plangent lower range into the stratosphere. Something feels “stuck in the middle,” she says. Levy tells her to fling her arms up in the air, like the Flying Nun, as she reaches the fifth note of each scale. This looks absurd, but when she does it, the studio, a 13-by-13 shoe box near Carnegie Hall, can hardly contain the result. The walls seem to flap. I expect Levy’s scented candles to gutter, the humidifier and space heater to short. It’s the most exciting thing I’ve ever heard.

It’s not a thing, though. “My voice isn’t an instrument I can just hang up on a hook,” McDonald tells me. It’s attached to the woman, and the woman seems anxious. She mentions her passaggio, the part of the range where the voice switches registers, and which, when it starts to get potholes, can indicate damage from age or overuse. But McDonald, who is 45, has been worrying about this at least since she won her first Tony, for Carousel, at 23. Her passaggio is fine, Levy tells her patiently. It’s not even clear to a layperson that she has one: The sound she produces is unified throughout her three-octave range. The thrilling “activity” of the low notes doesn’t thin out at the top; in fact, it blooms and intensifies. She is, Levy says, a “full lyric soprano” with enough power to fill an opera house, if not enough desire. (She has turned down many a Mimi.) Vocalism, for her, is the tool, not (as so often in opera) the product; in any case, it’s a weird tool. “The inside of my left ear starts to itch when we go that high,” she says apologetically, as if it were a sign of weakness.

“The higher the better,” Levy, a tenor himself, replies. “Singing that high, you deserve a lot of attention.” There does not appear to be any part of that sentence McDonald likes.

It quickly becomes clear that the Flying Nun maneuver is mostly a diversion: a way of sneaking McDonald past herself. For the same reason, Levy does not let her peek at the keyboard as he’s cuing her scales; there’s no need for her to know that he has worked her up to a high D-flat. Her inner panel of examiners is a busy bunch, and he’s trying to starve it of information that could be converted into needless self-criticism. (In the 45 minutes I spend at McDonald’s lesson, the word that most frequently passes her lips is sorry.) Instead he says, “Your voice is so healthy you don’t need to protect anything,” which makes her look pained, as if he’d said the opposite. She is warm and obviously adores Levy but is dead certain she hears things he doesn’t. “I’m Judgy McJudgerson,” she says.

Levy nods, undeterred: “The audience and I love what we’re hearing. Pretend you do too.”

But pretending is another problem. At rehearsals for Shuffle Along, the musical in which she’s starring this spring, she barrages the director, George C. Wolfe, with questions. “Sorry, but where are we — literally?” she asks about the opening scene, which finds all the main characters looking back on events of 1921 from some unspecified future. “Are we ghosts?” “No, real people,” says Wolfe. “We were here, and now we’re back.” She nods as if to say she’ll think about that. Later Wolfe tells me that, unlike some performers, McDonald doesn’t sequester her confusions or fears behind a front of personality: “There’s nothing she’s protecting.” When I ask if that leaves anything she won’t do onstage, he instantly says, in his two-syllable Kentucky drawl, “Lie.”

When I first interviewed McDonald 17 years ago, it had not been long, she said, since an African-American performer like herself found it almost impossible to get cast in Broadway roles that were not specifically black. (And few were.) Since then, a lot has changed, led in part by Disney musicals including The Lion King and Aida, with their multiethnic ensembles. But something more momentous seems to be happening right now in terms of diversity on Broadway. McDonald points out that along one block of 45th Street this spring, joining the long-running Lion King, are not only Shuffle Along, which begins previews March 15, but also The Color Purple, Eclipsed, and Hughie, with Hamilton and On Your Feet! one block north. Some of these shows are merely color-blind: That Forest Whitaker is playing O’Neill’s lowlife Erie Smith in Hughie (or that The Lion King’s pride is composed mostly of people of color) cannot be seen as an exploration of black life except to the extent that the stories are universal. But Hamilton, flipping this point on its head, is the opposite of color-blind — it’s colorized — deliberately casting nonwhite performers as white Founding Fathers to pry history open. The other shows are highly color-specific, addressing the experience of people not usually the subject of popular stage entertainment: abused African-American women, Cuban émigrés, captive Liberian “wives,” black stars of a bygone era. Even aside from stories, there is the matter of employment: The breakdown of jobs, onstage and off, creative and technical, is clearly changing. In several visits to full-company rehearsals for Shuffle Along, the only white people I noticed were Brooks Ashmanskas, who plays a clutch of smaller roles in the show; a press agent; and an assistant stage manager or two. And the producer.

McDonald allows that the situation for black artists on Broadway has “improved slightly,” but what if the current season is a blip? Still, I can’t help seeing the explosion of color as part of the energy feeding a Golden Age redux in New York theater (see here). The most exciting new works (and rethinkings of old works) often involve a folding toward the center of previously marginalized artists and subjects. And while not all of this energy has to do with race (gender, sexuality, and economic status are also in play), it seems to be the leading edge. Of course, race was a prominent theme of the original Golden Age: Among musicals, The King and I, South Pacific, Porgy and Bess, and many more dealt with struggles of otherness, mostly as seen from a white perspective. The difference is that in the new Golden Age the stories are usually being told from the other side.

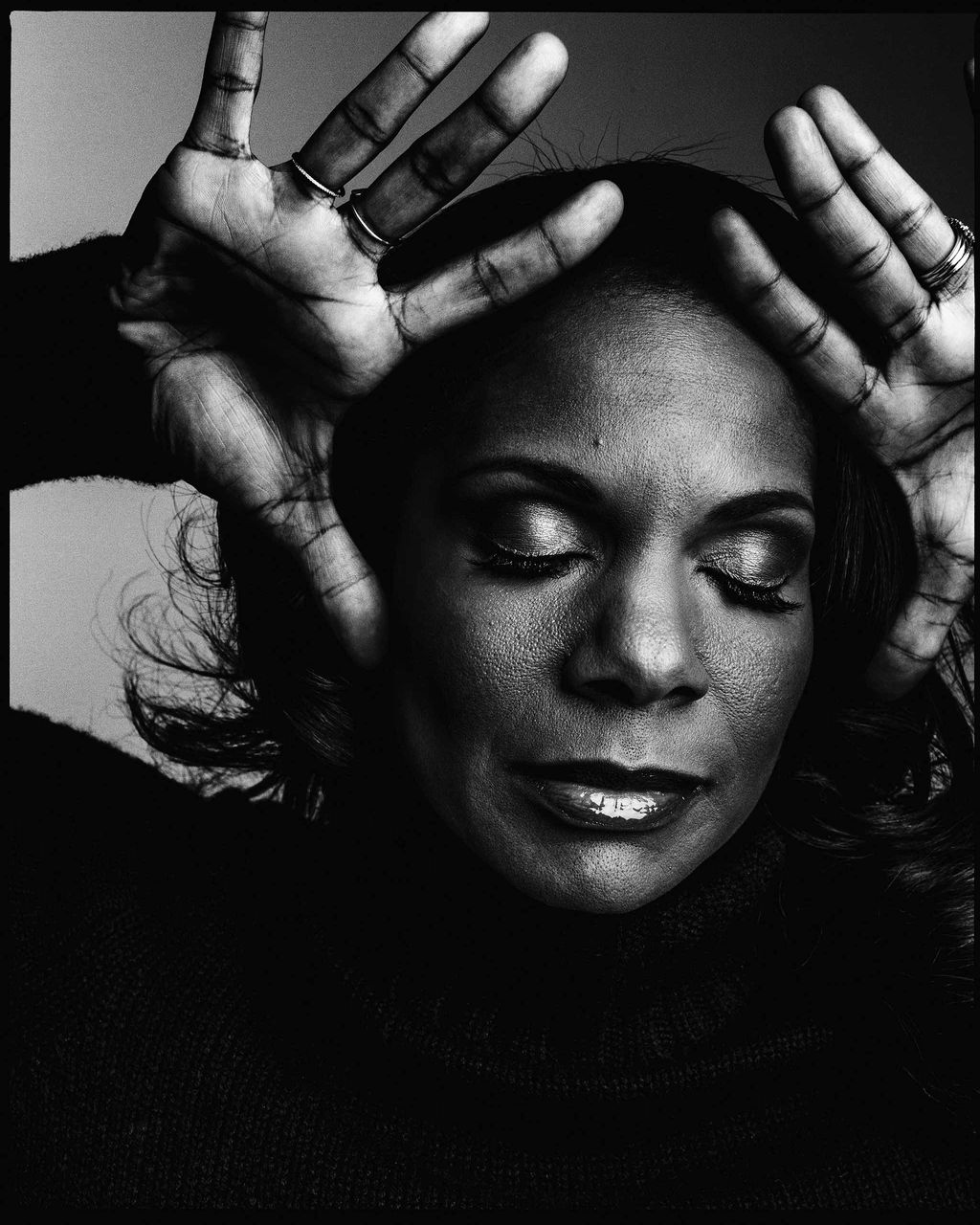

With her loyalty to the stage, and her six Tony Awards, McDonald has, over the 22 years since Carousel opened, been the inescapable face of that change. This is partly because she is Broadway’s greatest star singer, possibly ever — and I say that at a wonderful moment when the likes of Kelli O’Hara, Idina Menzel, and Kristin Chenoweth are also performing at the top of their respective forms. (Each of the four has a completely different kind of voice.) The combination of innate beauty, invisible technique, broad expressiveness, and dogged stamina — McDonald recently completed a 13-month, 63-city concert tour on three continents — means that her voice functions as one with her acting; her singing makes emotion audible in the same way a blush makes it visible.

But her prominence as the face of a changing Broadway is also the result of the way motherhood — her daughter, Zoe, is now 15 — has made her feel responsible to more than just her own artistry. What you use your voice for, other than tweets about gay marriage and homeless kids and moronic politicians, is a new question she worries about. She took on Shuffle Along not only for the chance to work with Wolfe (and a jaw-dropping assortment of other black stars, including Brian Stokes Mitchell and Billy Porter) but to honor her cultural antecedents. Without dislodging Judy Garland and Barbra Streisand from her girlhood pantheon, performers like Billie Holiday and Lena Horne — and now, in Shuffle Along, Lottie Gee — have come to the fore, as much for their talent as their nerve. Accepting her most recent Tony, for playing Holiday in Lady Day at Emerson’s Bar & Grill, she saluted a list of black artists who “deserved so much more than you were given when you were on this planet.”

What McDonald feels she herself deserves is a thornier matter. Certainly not another Tony; winning so many in so many categories — a probably unbreakable record — has been gratifying, of course, but also overwhelming. Over dinner one evening, she tears up talking about it, as if she had gotten them fraudulently. “When I am in the pharmacy, I don’t say ‘I am picking up my prescription for six-time Tony Award winner Audra McDonald,’ ” she exclaims. So vigilant is she about not seeming grand or entitled that you can’t help wondering what phantoms she’s boxing. She fills her conversation with self-mockery, praise for others, and just-folks enthusiasms. Waiting for appetizers, she pulls from her purse a packet of Sweet Sriracha Uncured Bacon Jerky and begs me to try some. “You’ll see Jesus,” she promises, then reconsiders. “Maybe that’s not the most important thing to you.”

If she has disappointingly few starry affectations — she hates wearing gowns, consumes carbs in public, and, as Lonny Price, the director of Lady Day, often says, “would rather chew a big bucket of glass than take a bow” — she still gives a poor imitation of normalcy. You can feel the effort of her constant self-management coming off her like heat; it’s as if, lacking much criticism from critics, she must make up for it internally. I am strangely reminded, listening to her, of the way people talk when taking responsibility for past sins or working their way out of debt. In her case, though, the debt isn’t monetary, it’s emotional: “Without theater, I don’t think I would have thought I was a smart person or excelled at anything.”

She lets the sadness of this statement ride for a moment but then, characteristically, wrings it into something else. “Three nights ago, I watched The Lady and Her Music on YouTube,” she recalls. “And even though Lena [Horne] was a sweaty mess, and Hollywood didn’t think she was pretty when she sang because her mouth was too big and she opened it too far, she was out there celebrating herself and demanding that you celebrate her too.” In some gifted performers, survival becomes a kind of moral example: a chance, she says, “to reach back through the door of opportunity” — she’s quoting Michelle Obama — and help others through it. “So that maybe a black girl who sees me can say: ‘That lady with most-of-the-time-nappy-frizzy hair, who’s not rail thin, she did it, that’s a possibility.’ ”

That the door of opportunity swings in two directions is the starting point of the 2016 Shuffle Along, which more than any show I can think of aims to reshape our perception of blackness on Broadway. The subtitle alone — The Making of the Musical Sensation of 1921 and All That Followed — suggests the size and nature of Wolfe’s metahistorical intentions. His libretto includes elements of the original Shuffle Along,especially the songs by Eubie Blake and Noble Sissle, but largely replaces its lightweight story about a rigged mayoral election in “Jimtown, USA” with a backstage look at that show’s creation and a brief for its importance. As Lottie, the star of the show within the show, McDonald flirts, sasses, plays comedy scenes, tosses off coloratura roulades, and even taps. In short, Lottie is no one’s tragedienne except in the sense that time has entirely erased her, as it nearly did Shuffle Along, despite its being the most successful early Broadway musical with an all-black cast and creative team. Blake, who died in 1983 at age 100, is still somewhat known from the 1978 Broadway revue Eubie! But the others, and their achievements, are forgotten. Wolfe aims to show how they, and by extension black artists in general, made Broadway what it is: “Dancing girls? All that shit you love? We did that.” In that sense, Shuffle Along is a transitional work of revisionist history, an act of reclamation disguised as a frolic.

It also represents a kind of passaggio in McDonald’s career. She grew up in a mostly white middle-class neighborhood of Fresno, California, with jazz, Broadway, classical, and opera always playing. Both her parents’ families were musical; five aunts on her father’s side toured as the gospel-singing McDonald Sisters. In that environment, she told me in 1999, “you’d better sing well or you might get sent back.” Her own taste favored the extreme and romantic, as befit her “super-dramatic” style: hyperactive, terrified of thunder, kicking teachers, throwing tantrums. Her parents, who would divorce when she was 14, handled her as gently as they could (“Here comes the circus,” her father would say), but her anxieties were not easily tamped. When she cried that the world would come to an end some day, it was not enough comfort to say, as they did, “Yes, but not just to you.” She needed Ritalin — or musical theater.

The McDonalds chose the latter, taking her at age 9 to audition (singing “Edelweiss”) at Roger Rocka’s Good Company Players, a local dinner theater. Performing in cabarets there — she was cast at first as an alternate in the junior troupe — was a huge relief, even if it further alienated her from the prevailing culture of her non-theater peers, who were listening to the Go-Go’s while she belted “Losing My Mind.” But the theater was not a perfect haven: Though Fresno in the ’70s and ’80s was fairly well integrated, Roger Rocka’s was not. Neither she nor her younger sister, Alison, could get cast, she says, in “white” shows like The Sound of Music, and their parents would not let them take the “demeaning” roles they were offered, like “the one little dimwitted black girl” in The Miracle Worker. Raw talent won out; at 16, McDonald even played Evita there. But having screamed at her second-grade classmates that they could never understand what it was like to be the only black girl among them, she now, in high school, faced kids saying she wasn’t black enough. With her fancy voice and big dreams, they thought she was “stuck up,” an accusation she still works assiduously, 30 years later, to disprove.

Not that those dreams were so outlandish. “I just wanted to be on Broadway,” she says; chorus, understudy, swing, she didn’t care. Getting into Juilliard in 1988, even as a classical voice student, seemed to bring her close to her goal, but it wasn’t close enough. Watching Patti LuPone give one of the greatest musical-comedy performances of all time in the revival of Anything Goes then running, she wept and wept. That’s what she’d meant to be doing, and as she slogged on at Juilliard, the goal seemed even further away than it had in Fresno. She gained weight, ditched classes, and eventually, at age 20, attempted suicide, cutting her wrists.

McDonald talks about this matter-of-factly today, to keep it from festering as a secret, but doesn’t seem to see it as a determinative moment. Still, it’s hard not to notice that the roles she’s played on Broadway since that Tony for bubbly Carrie Pipperidge add up to a dossier of extreme unhappiness. (And even her Carrie, she recalls verbatim, was criticized as “militantly charmless” by this magazine’s John Simon — “as if I were raising a black power fist.”) In Master Class (Tony No. 2), she was a shaky young soprano savaged by Maria Callas. In each of her next two shows, she tried to kill one or more offspring, failing in Ragtime (No. 3) but succeeding in Marie Christine (no Tony for that). After a brief vacation as the merely exhausted Ruth Younger in A Raisin in the Sun (No. 4), she returned to form as two title drug addicts, first in Porgy and Bess (No. 5) and then in Lady Day (No. 6).

Lady Day was the last word in McDonald’s misery-mongering; welding her own strength to Holiday’s fragility, both vocally and emotionally, made for one of the greatest tragic performances I have ever seen. (A version filmed before a live audience will air on HBO on March 12.) But she has also made a subspecialty in the more delicate loss of bereaved Shakespearean women, playing Lady Percy in Henry IV and Olivia in Twelfth Night. Sometimes it seems she has spent more of her career onstage crying than singing. (And that’s not even counting the shelved production of ’night, Mother, in which she was to star, opposite Oprah Winfrey, as a daughter set on suicide.) On television, she has a less tragic profile, including four seasons as the best friend on Private Practice, but even so, her most convincing small-screen appearances are noticeably dark. Singing “Climb Ev’ry Mountain” as the Mother Abbess in the live Sound of Music in 2013, she seemed likely to swallow poor overmatched Carrie Underwood whole. On Jimmy Fallon’s Tonight Show, she frequently shows up to croon the text of actual Yahoo! Answers (“Water is exactly 0 percent celery”) in the manner of a lounge chanteuse who makes heartbreak out of anything.

It was partly for a break from this litany of sorrowful ladies that McDonald chose Shuffle Along, even though it meant a complicated rejiggering of schedules. (She will take a nine-week break from the show to perform Lady Day in London, opening June 25.) In roles like Bess and Billie, she says, tapping her forearm, “I eventually get to the point where I don’t have any more veins.” But in Shuffle Along, she doesn’t shoot up, or kill anyone, or die; she gets to look as beautiful as she actually is. This doesn’t mean that her Lottie is a purely comic creation. In McDonald’s hands, a bouncy comedy song like “I’m Craving for That Kind of Love,” in which Lottie teaches the new girl, Florence Mills, how to style her big number, turns into a mini-cabaret of mixed emotion. The comedy comes from the fact that Florence is already a great singer; she would soon be a far bigger star. That’s the source of the pathos, too. Lottie can feel history nibbling away at her.

So can McDonald. It hardly seems possible that she now has a second generation of fans, but Adrienne Warren, who plays Florence, tells me that in her house, growing up, “it was Mama, Jesus, and Audra.” (Warren is 28.) Zoe, McDonald’s daughter, recently said, “Mommy, my social-studies teacher told me she saw you in Ragtime when she was 12. Isn’t that neat?” McDonald answered, “No, that is not neat. I’m going to lie down.”

McDonald lives in a small semi-attached house in Inwood, at the very top of Manhattan, with her second husband, the actor Will Swenson, whom she married in 2012. They are joined there at various times and on various schedules by Zoe, who spends half the week with her father, and by Swenson’s two boys, Bridger and Sawyer, from his previous marriage. At their larger home in Westchester, they are also joined by McDonald’s mother, Anna, a retired university administrator, who lives next door. Swenson admits that he still sometimes thinks, when watching McDonald get the kids ready for school, Holy crap, I live with her! Rehearsing with her last summer for a production of A Moon for the Misbegotten at the Williamstown Theatre Festival, he found himself flipping between awe at her stage prowess and the need, as her husband, “to be supportive and cautious.”

She flips too. The anxiety I see whenever she rehearses — and which Wolfe says isn’t anxiety but “intensity, baby!” — dissipates quickly afterward. The routines of motherhood have stabilized her, she says. In a car heading home from a taping in the Village, she telephones Zoe, whose location she confirms with an app. Zoe has just been cast as one of the sorority girls in a youth theater production of Legally Blonde, but is also doing three other shows; McDonald gradually convinces her she should let at least one go. “She’s a terrific little performer,” McDonald says afterward, looking proud and a little afraid of the familiar intensity. “But she’s under no illusions that performing is glamorous. How could she be?”

I’m enough of a fanboy to have hoped for a bit more glamour, a tiara or a personal chef, but McDonald wears too much makeup onstage to want to wear any in life. Anyway, she’s too busy for much luxury. On this particular day, even with Zoe at her father’s, she will have spent more than 12 hours working, moving from a long rehearsal for Shuffle Alongto the taping in the Village (for a documentary about Terrence McNally, who wrote Master Class and Ragtime) to several hours of serious attention to whatever I ask her, as if she were being graded. One thing I raise is a comment she made during the McNally interview. The thing she loves in his work, she said, is the way it suggests that within any person you might pass on the street, a whole opera, completely invisible to the world, is occurring. What about her opera?

“I used to think I needed to have drama at all times or I wouldn’t have the fuel for the performance,” she answers. (Famously, she fainted during her final audition for Carousel.) “Now I know that’s not true. That doesn’t mean I don’t feel it, but I recognize it when I do, and put the brakes on. And if the performance isn’t what it might have been once, I’ve learned not to judge myself as much.”

Really?

She makes a “maybe” face and laughs. “I don’t see myself as a perfectionist. I mean, look at me! So if I can’t hold that note the way I used to after only six hours of sleep, so be it. I just try to keep the truth in the storytelling. And when I’m singing now I’m also trying to reassure the audience: I got it, I’m good.

“Now, don’t let me fool you. There have been times, especially with Lady Day and flying everywhere, when I’ve wondered, Oh God, have I permanently damaged my voice? The doctor couldn’t find anything and Arthur couldn’t hear anything, but I knew something was wrong. Finally a friend said: ‘I think you’ve got something stuck in your throat. Something you need to say.’ Which is very New Age, I realize. But then when I did get something off my chest I’d been needing to say, the next day I had a recording session at 10 a.m. I should have sounded like cr-cr-cr-crap and instead my voice was” — but she won’t give herself the compliment.

If today she handles her drama better, it can still take her a while to catch on to herself. Last April, just before a concert at Carnegie Hall, she threw her neck out “while reaching for a jar of peanut butter or something.” Her osteopath, reviewing her chart, noticed that she’d often presented the same symptom, always on the same week of the year. Had anything significant happened around that time? “I said, ‘I don’t know,’ but then I remembered: It was the week my father died.” On April 29, 2007, Stanley McDonald Jr., a retired school superintendent and experienced aviator, was flying an experimental gyroplane north of Sacramento when it tilted, flipped over, and plummeted to the ground. He was 62. The call came later that day, on the street outside Studio 54, after the Sunday matinee of 110 in the Shade. She missed just three performances.

“I feel it every day. Of course. I am so sad he’s not seeing Zoe grow up, and I” — here she makes a noise not unlike a humming vocalise. “I mmmmmmmmiss him! Ironically, he was the one who could calm my fears about flying: He said, ‘Turbulence doesn’t hurt the plane.’ But I know he would not want me to make it dark. He would kick my ass. He’d say, ‘Then what was the point?’ He loved flying his planes. He was doing what he loved. And so am I.”

“I’m hyperventilating,” says Blake Devillier, a clothing retailer from Dallas. “I’m having an out-of-body experience.” He has flown to New York to claim the grand prize for contributing $2,250 to Covenant House as part of a “Broadway Sleep-Out” fund-raising challenge McDonald supported. Lesser prizes include recognition as a “cool” person on McDonald’s Facebook page ($50) and a “singing telegram” from the site of the sleep-out itself ($1,000). As the top contributor, Devillier gets dessert with McDonald at Sardi’s and then a private tour and a song at the organization’s West 41st Street facility. “I’ve heard you sing on Jimmy Fallon,” he burbles, “and now I’m having hot chocolate with you!”

McDonald began working with Covenant House, the agency for homeless youth, almost by accident. In 2014, looking for appropriate opening-night presents for Lady Day, she walked from Circle in the Square to the shelter to make a donation in her colleagues’ honor. Outside, she chatted with guards and was impressed to see them “leap into action” to help a homeless girl just arriving. Later that year, she joined the board. But it wasn’t really an accident, of course. Holiday was a homeless girl, too, or nearly, who might have had a less tragic life had she ended up in a shelter instead of a brothel. And McDonald certainly knew what it felt like to have required rescuing, if only from herself. The theater, which taught her how to make use of her exposed nerve endings, was her shelter. Perhaps it saved her literally, too: When she got out of the hospital a month after her suicide attempt, Juilliard encouraged her to accept an offer for the national tour of The Secret Garden before returning to finish her studies, which she did a year later. But for a while at least, instead of taking German-diction and ear-training classes, she was actually performing, which was all she ever wanted, or needed.

At Covenant House, walking her guests through unglamorous rooms, she seems lighter than I’ve seen her, as if an inner and outer pressure were equalized. She hugs staff members and chats with the clients, asking them what they hope to do. Later, she will spend the night in a sleeping bag, on a wafer of cardboard, under some scaffolding, not getting much rest while enjoying the rhythmic sound of trucks and the drumbeat of rain. But now, at the end of the tour, in a small, empty classroom, she closes her eyes and sings a McGuire Sisters hit for Devillier: “May you always be a dreamer / May your wildest dream come true.” The walls, lined with vocabulary words and linear equations on cutout pieces of construction paper, start to rattle, as if lifting off. She opens her eyes and smiles broadly, seeming to say: I got it, I’m good. Turbulence doesn’t hurt the plane.

*This article appears in the March 7, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.