He’d never make you feel bad for asking, but Don Cheadle has for a decade now been telling the same story about how he wound up directing and co-writing his first feature. In the highly unconventional biopic Miles Ahead, he plays Miles Davis (or rather the essence of Miles Davis, with the truths thrown up in the air and rearranged in the key of B-flat). When the iconic trumpeter was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2006, reporters asked Davis’s nephew Vince Wilburn Jr. if the family was planning to make a movie of his uncle’s life. “He said, ‘Yeah! And Don Cheadle’s gonna star in it!’ ” says Cheadle, bugging his eyes out for effect. Cheadle is in the midst of a series of Q&As at the 2016 South by Southwest Film and Music Festival (SXSW) in Austin, Texas, and he waits for the laughter to die down before pointing out Vince in the crowd. “People started calling me, saying, ‘Well, Vince says you’re doing the movie.’ ‘What movie?!’ ” He and Vince had never met.

I first heard Cheadle tell that story at the movie’s world premiere at the New York Film Festival in October, and again in person when he and I met up to talk in Austin, and yet again when he introduced the movie at its SXSW premiere the following night (which was running so late Cheadle joked that it was on “CPT,” or “Colored People’s Time”). Somehow, though, he’s wrung a laugh out of me every time. The movie finally opens April 1, but Cheadle seems to be getting looser and more animated, like a stand-up or, yes, a jazz musician, getting high off riffing on the same material a different way every night. Which means switching on his Miles Davis rasp to tell the story of Herbie Hancock’s first session with Davis: “Herbie’s looking at Miles, like, ‘What am I supposed to play?’ And he’s like” — rasp — “ ‘The piano, motherfucker!’ ” (Later, asked why he doesn’t do more comedies, Cheadle snaps back that no one ever asks. “Kevin Hart is doing all of them.” Pause for laughter. “Fucking Kevin Hart.” Pause again. “Who actually was a contributor on the film. Thank you, Kevin.”)

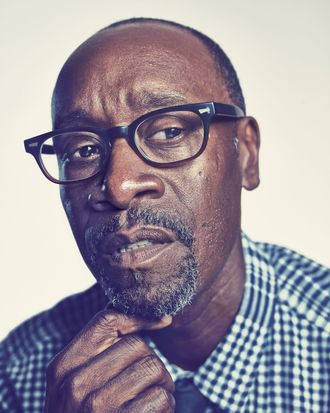

Don Cheadle walks into a room like he’s casing it out, confident but watchful from behind dark sunglasses that, at least when talking to me, he never takes off. A wiry five-foot-eight, Cheadle has a sharpness to him, an air of constant thoughtfulness that makes him the most interesting part of most movies he’s in. As we sit on a bench in the sun-drenched backyard of Austin’s Four Seasons Hotel, Cheadle tells me about the first play he ever did, a fifth-grade production of Charlotte’s Web, in which he played Templeton the Rat. “I remember going to a little café up the street and studying my lines,” says Cheadle. “I wanted to be off-book very early. I wanted to know what a rat was thinking and feeling.”

It’s an energy not unlike Davis’s, who, despite his Birth of the Cool reputation, Cheadle tells me, used to throw up before he went onstage, every time. For years people who actually knew Davis, like legendary drummer Albert “Tootie” Heath, had been telling Cheadle he ought to play him. But Cheadle wasn’t interested in a straightforward cradle-to-grave treatment like Ray or Walk the Line and felt confident that Davis, who hadn’t liked Clint Eastwood’s 1988 Charlie Parker biopic, Bird, wouldn’t want to be the subject of one.

He suggested the idea of a heist movie, set during Davis’s cocaine-addicted dark period, from 1975 to 1980, when he stopped making music and holed up, Howard Hughes style, in an apparently fetid Upper West Side mansion. In the final version, there are gunfights and car chases, all over the possession of the single unheard session tape Davis made in this period. “I just thought that a movie about this person needed to be as mercurial and unexpected and improvisational as his music was,” Cheadle tells me. “As opposed to a movie that’s, like, checking off all the boxes about Miles Davis’s life.”

The marquee Cheadle imagined, he says, was “ ‘Don Cheadle is Miles Davis as Miles Davis in Miles Ahead.’ ” Certain things did actually happen, such as Davis’s 1959 beating and arrest at the hands of the NYPD outside the jazz club Birdland for escorting a white woman to a cab. As for the rest, Cheadle says elliptically, “What’s true is the spirit, what’s ‘real’ is that it’s truly Miles Davis–esque.” Some people may quibble about omissions, that, for instance, the movie doesn’t focus enough on Davis’s spousal abuse. “Twitter beef? Blog shit. Whatever,” says Cheadle.

As he struggled for years to secure financing — eventually turning to an Indiegogo campaign after an HBO theatrical-distribution deal fell through — Cheadle went deep on the role, reading every book written about Davis and taking up boxing, a passion of the musician’s, even though there are only about two minutes of screen time when he actually needs it. He also spent eight years learning to play the trumpet: He’d always been annoyed by movies about musicians where the actors’ fingers don’t move in sync with the notes and wanted to make sure that whenever the moment came, he’d get it right.

Eventually, Cheadle persuaded the Davis family to let him bring in screenwriter Steven Baigelman to help retool the script into something more palatable to foreign-sales teams, which meant writing in a role for a white co-star. Enter Ewan McGregor as David Braden, a shady but game-for-anything Rolling Stone reporter aiming to write Davis’s comeback story. The racial issues involved in making Miles Ahead seem particularly pointed given the recent uproar over the all-white field of acting nominations at the Academy Awards this year. When the nominations were announced, Cheadle tweeted to Oscars host Chris Rock that he’d see him there: “They got me parking cars on G level.” (And Cheadle is someone who’s actually gotten a Best Actor Oscar nomination, for 2004’s Hotel Rwanda — and might be in the mix again for this movie.) He didn’t go this year, he says, not because he was boycotting but because “it’s not fun.” He believes the problems that led to #OscarsSoWhite don’t lie entirely at the feet of the Academy. “That’s a symptom of things that are not happening inside the halls of power where movies are being decided,” he says.

Spike Lee has said things won’t change on a fundamental level in Hollywood until people of color are in the room. Does Cheadle’s position at Showtime’s House of Lies — on which he has been a producer, writer, and star for five seasons — count? “I don’t know,” he says. “I’m in a room. I’m in my room. I think the rooms change, and it depends on when you ask. Come back in five years, it’s like, Oh, you’re not in the room anymore. This business retires you. You don’t retire from the business very often. I know very few people who’ve ‘made it’ and feel like they are just good now and don’t have to hustle anymore. There are probably three or four, and two of them are wrong.” It’s a good line, and I’ll hear it twice more from him before leaving Austin. Just part of the hustle.

*This article appears in the March 21, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.