Heart is overrated in comedy. Soul is where the heart is, and soul means realness. Honesty. Penetrating insight. Undeniable truth.

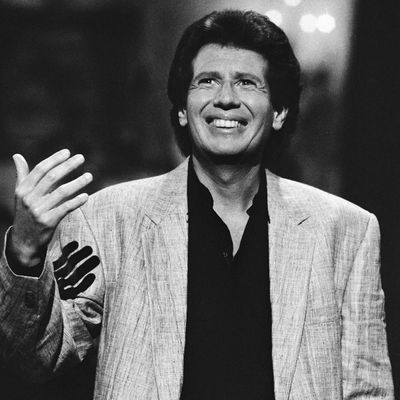

That was the crucial realization of the late Garry Shandling, a giant of stand-up comedy and one of the greatest artists American TV has ever seen.

The 66-year-old writer, actor, and filmmaker, thought to be in good health, died today, of unknown causes, in a hospital, not long after a 911 dispatcher received a call from his Los Angeles home. He was born in Chicago, raised in Tucson, Arizona. His comic persona, honed over 30 years onstage and in TV and film, fused Jack Benny’s unctuous neediness, Charles Grodin’s dour certitude, Albert Brooks’s self-lacerating intellectual discomfort, and Warren Beatty’s dashing Hollywood satyr act, and added shadings from Shandling’s own personality, plus a great playwright’s keen understanding of the lies that we tell ourselves about ourselves, and how these self-deceptions become plain whenever we try to manipulate others to attain what we think of as happiness.

Most comedians can only fantasize about making a single classic TV series, but Shandling made two: Showtime’s It’s Garry Shandling’s Show (1986–1990) and HBO’s The Larry Sanders Show (1992–1998). He taught a generation of performers and filmmakers that it was possible to balance daring formal experimentation with character-based comedy that saw through people’s delusions, even as it showed compassion for their loneliness and craving for validation. He made the kind of comedy you could barely stand to look at because it was so mercilessly acute, and that you couldn’t look away from because it accurately reflected the harshest truths of human interaction.

His work often dealt with the craving for recognition and the misery that ensues when people receive it: the idea of fame and money as emotional and intellectual drugs, alluring and addictive, satisfying and deeply unsatisfying. The idea that the only thing worse than not getting what you want is getting what you want was rarely articulated more clearly than in Shandling’s work. His two classic TV shows and his stand-up amount to an unmatched legacy of innovation and craft. Ask anybody who tries to make people laugh and think, and they’ll tell you that Shandling’s work meant something. He showed us what was possible.

It’s Garry Shandling’s Show was a well-kept secret, for the most part — Emmy-nominated and critically acclaimed, but never a mainstream success. The show’s theme song, which repeated “This is the theme to Garry’s Show” over and over, cut to the heart of Shandling’s obsession with artifice and authenticity and how they’re two sides of a plug nickel. The theme song was a terrible theme song, a non-theme-song practically, but it stuck in your mind and brought a smile to your face, so that made it a real theme song.

The set was a set. Garry told you it was a set. He even walked you through the set. Sometimes he indicated the cameras, the lights, the backdrop, and he always acknowledged the studio audience (like Jack Benny before him). The Luigi Pirandello of the three-camera sitcom, Shandling told you, over and over, This is all fake, these lines were written down, these characters are just constructs, and then made you laugh and feel anyway. The artifice of his show offhandedly became a representation of the artifice of personality, personal presentation, the construction of our Life Story as a tidy Hero’s Journey that made us look better than we’d look if anyone else were telling it. Often he’d rewrite scenes or lines within a moment to salvage a personal disaster or create a happy ending where none had any right to exist. We laughed and cringed at this, because we do it ourselves every day, in large ways and small.

The Larry Sanders Show — which holds the personal distinction of being the series that made me order cable for the first time — felt in some ways like an inversion of his Showtime classic, or maybe a Cubist splintering of it. Shandling played the title character, a Johnny Carson–like talk-show legend who was perpetually terrified that he wasn’t getting the best guests, that his “best friends” in showbiz didn’t even like him and only hung around him because he was a star, and that his co-workers only put up with his crap because he was paying them. On some level, all of these fears proved accurate, and on another they weren’t true at all. All the other recurring characters and guest stars on the show were just as screwed up as Larry — they just didn’t usually have his wealth and power, so they had to suffer indignities without recourse. The “backstage” scenes were shot on film, in the graceful yet spontaneous manner of a low-budget indie comedy, while the talk-show segments were represented by cutting between brighter, grainier videotape (representing what the camera sees, and what the audience at home experiences) and filmed images of his staff and crew and backstage acquaintances reacting to his performance. That these textural (and textual) distinctions immediately started to seem arbitrary was part of the show’s point, and part of its philosophical richness. Life was all one big show here, and nobody had the script.

Few lead characters in TV comedies were as pathetic and needy and sleazy and manipulative as Larry. He took his wife for granted until she finally divorced him. He hit on every halfway-attractive woman who crossed his path (and a few of them went home with him, not because they really liked him, but because he was Larry). He’d bring dates home with him from dinner and then make them watch the broadcast of that day’s show with him, solicit compliments on his excellent work, and feel genuinely hurt when he had to coax the praise out of them. Larry was a great performer, and it’s a testament to Shandling’s physical and verbal skill as a performer that you could watch Larry interact spontaneously with guests in barely scripted “segments” and think, Carson could not have done that any better. But he was a terrible boss, petty and entitled, casually sexist and racist and homophobic, though often not as crude about it as some other people in Hollywood, which allowed him to congratulate himself on being oh-so-very liberal. (Except for Albert Brooks, few filmmakers skewered this aspect of showbiz delusion with such precision.) We should have hated him, but we couldn’t because, like The Office’s David Brent and his counterpart on the American Office, Michael Scott, we saw how lonely he was, how miserable he was in his own skin, and thought: That poor bastard. I’m glad I’m not him.

But you were, though. Shandling knew it, and you knew it. And that’s what gave The Larry Sanders Show and It’s Garry Shandling’s Show their slow-motion, train-wreck fascination.

You can’t always get what you want, and contrary to the Rolling Stones song, you can’t always get what you need, either, because life is long and confusing and tough and people tend not to be evolved enough to imagine their way out of their own bubbles and get the perspective necessary to realize what’s important and what isn’t. You think you’re moving forward but a lot of times you’re running in place. You think you’re being brave in showing people who you really are, but sometimes you’re just giving them too much information. You take love and friendship for granted until love and friendship acquire ironic air quotes and you can’t recognize the real thing anymore. You diagnose other people’s problems with clarity but cannot discern the depth of your own brokenness. You work so that you don’t have to face any of that. You run away from yourself to find yourself and then come back and become the same deluded person you were before. You feel things deeply but wonder if you’re really feeling them at all.

No, that’s not me, thinks the resistant viewer. That’s you, Garry. Or Larry. Or whatever name you have assumed for this film or TV show.

But it is you.

Shandling got this. And he did everything in his power to help us get it, too. He held the mirror up, and we saw his face in it, and if we stared at it long enough, we started to see the resemblance.