Thanks to the megahit Batman v Superman: Dawn of Justice, Wonder Woman is on the minds of moviegoers around the world. But unlike her peers Batman and Superman, Wonder Woman’s story isn’t as well-known in the collective consciousness. Comics writer Grant Morrison is angling to change that. Over the course of his three-decade career, Morrison has shown that he knows how to take a classic superperson — Superman, Batman, and Wolverine being just a few notable examples — and identify precisely what makes their archetype compelling. He’s also a devious and inventive creator of all-new characters in his creator-owned titles like Nameless and Annihilator, but he’s never too proud to jump in the water with an existing icon. Now, it’s Wonder Woman that has his attention.

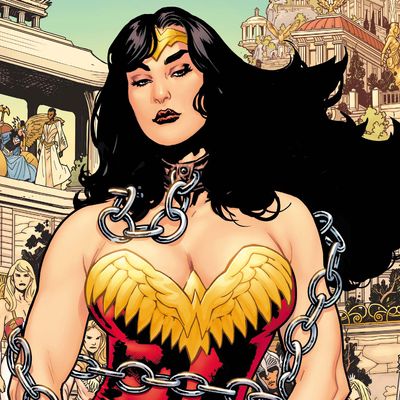

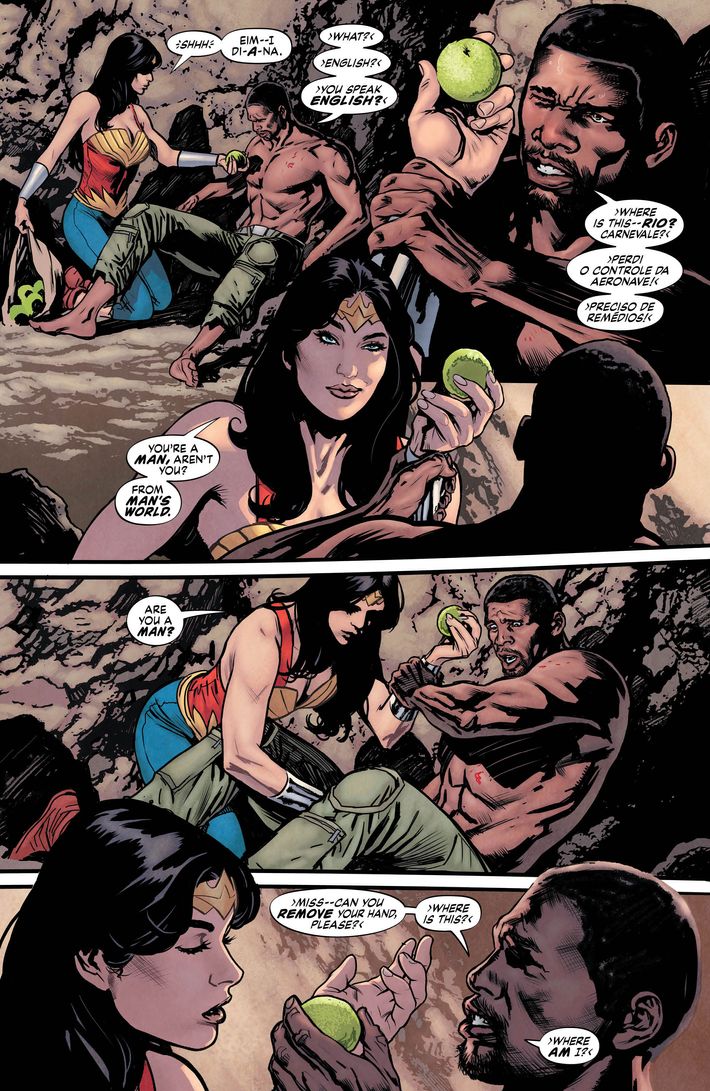

This month, his long-anticipated Wonder Woman: Earth One, Vol. 1 will hit stands after years of him teasing its existence. Penciled by superstar artist Yanick Paquette, the self-contained story reimagines the fighting Amazon’s origin and places her in something resembling the real world. We caught up with Morrison to talk about the character’s roots in the world of bondage and kink, his decision to make longtime Wonder Woman love interest Steve Trevor black, and her relationship to feminism.

What was the first Wonder Woman story that spoke to you as a reader?

Honestly, I don’t know if I read Wonder Woman so much. When I was a kid, I liked Superboy and my sister liked Supergirl, so Wonder Woman seemed a bit of a grown-up. She didn’t seem quite in our age group, y’know? So I guess the first Wonder Woman that really stood out for me was the TV show, the Lynda Carter show. I could finally see the character, how it worked, and how it made sense in a wider context.

What was compelling to you about that show?

Just the fact that it worked so well! It was really believable. But as a younger person, obviously, all that stuff was believable. I was completely convinced by Adam West [in the Batman TV show], as well. He was Shakespearean! [Laughs.] Wonder Woman was so populist. There’d been so many different versions of her since her creators, William Moulton Marston and Harry Peter, the artist, actually told Wonder Woman stories. And obviously, going back to those stories, they became my favorites of all. They were the weird, pure expression of the character. But I loved the TV show because it could take something that essentially, to me, is quite weird and driven by the kinks of its authors and make it really populist.

Wonder Woman is depicted in your book as being queer and into bondage kink. Why was that important to include?

Honestly, for me, it’s loyalty to the source material. Those early stories are very heavily bondage-oriented. Seen now, they’re quite startling in their imagery. They seem outrageous. Honestly, what we’ve done is tame, by comparison. We felt she needed to be written in that way. There’s a sense that you cannot say that a society of 3,000-year-old women gave up having sex because they fell out with men. That’s not necessarily something that needs to be dwelt on or brought to the obvious fore in the way Marston did, but I certainly think Wonder Woman does have to acknowledge that debt and kinda has to carry the standard for the alternative and the queer.

You’re known for being able to boil down a character to its core tenets. How did you get at the essentials of Wonder Woman?

I went right back to the original stories about Wonder Woman because I thought there was interesting material that was kinda untapped. As you know, they were driven by this strange, alternative lifestyle of Marston and his wife and associates. [Note: Marston was something of a libertine, living simultaneously with his wife and his lover, as well as writing at length about dominant-submissive relationships. He also believed that women should rule the world and was involved in the early feminist movement. For more, read Jill Lepore’s writing on Marston.] So Wonder Woman emerged from this weird, steaming stew of alternative lifestyles and polyamory. It was all being expressed as this idea of the ultimate female superhero, who would conquer with love rather than violence. And I think what people have forgotten, and the essential thing for my take on the character, is she fights not with sword or shield. Originally, she fought with a pair of bracelets which could repel any weapon because she was so skilled, and her lasso, which made people obey her every command. Those are insanely brilliant ideas as weapons! They are the weapons of peace.

Where in Greek mythology did you look for inspiration?

Weirdly enough, one of the things we talked about was to not root this too much in mythology. Apart from the opening sequence, which shows, just as in the original Wonder Woman story back in 1940, kind of “how the Amazons came to be,” basically. It’s Hippolyta and Hercules, and he imprisons the Amazons and steals her magic girdle, which makes him invulnerable. The Amazons fight back, escape, and establish this island. So that was a bit where I took the original story from Marston and fused it a little bit with traditional Greek mythology, even though Hercules has obviously a completely different career trajectory in Greek mythology. I wanted the images from the mythology, and also Yanick did these beautiful Greek-pottery-shard panel layouts.

But that aside, there’s not a lot of Greek mythology in this. We want to present the Amazons less as a culture trapped in the Greek past and more as one that’s evolved over 3,000 years. They have technology, they have machines, they have these purple-ray devices that utilize energy in a way we can’t imagine. It was definitely very much an advanced culture, but it’s one that exists in a weird state. Every day is summer, y’know?

This is a story with strong feminist overtones, but you and the book’s other creators are men. Did that concern you?

Well, of course, until we thought, Well, it’s the same story when you look back at Marston and Harry Peter. Here was a tag-team of men writing about women. All you can do at that point is say, Well, yes, we did. We wrote a character. I wouldn’t like to say it represents all women. I tried to do my research to get at least a flavor of feminism in. I couldn’t necessarily say that what Marston was doing was utterly feminist. It had a very strange, different slant. We just wanted to be faithful, at least, to some of that stuff.

I think Wonder Woman became more associated with feminism in the ’70s, when Gloria Steinem used the character as a figurehead. But yeah, it’s always — you’re walking a tightrope. But lots of women have written Wonder Woman comics. It’s not like we’re the only people doing one. Or doing the definitive one. If people want to see a Wonder Woman comic done by women, there’s a lot of great ones out there.

In Jill Lepore’s book about Marston and the origins of Wonder Woman, The Secret History of Wonder Woman, she argues that the women in Marston’s life had a huge influence on what went into the stories.

Oh, I’m sure! That was obvious, yeah.

Have you read Lepore’s book?

No, I actually haven’t. It’s on order. [Laughs.] I kept away from pretty much everything. I obviously know it exists and I look forward to reading it, because I know it’ll be — hopefully, this is a trilogy of books and I’m sure that it’ll inform whatever happens next. I’m looking forward to it, but I haven’t seen it yet.

Ooh, you want to do a trilogy?

Yeah, I’d like to. Yanick and I have thrown it up in the air. To me, we’ve barely scratched the surface of a lot of the ideas that we’ve discussed. There’s more to be said.

You reimagined Wonder Woman’s sidekick from the early Marston and Peter stories, the curvy and audacious Etta Candy, although you rename her Beth Candy. How do you approach such a goofy and slightly offensive character in 2016?

I think she’s only such a relic in the sense that her name was that. [Laughs.] That’s the one thing that we changed. “Etta Candy” just doesn’t fly in the modern world. It goes back to a time in comics when you had characters named “Ivana Millionaire” and stuff like that. So it is slightly ridiculous and we changed that. But as a character, I felt she was a really important character in the first place. The idea of a very fierce and rambunctious young college girl who didn’t really care what weight she was because she seemed to be able to do anything. She could fight any battle. She could turn up anywhere. She had Wonder Woman’s back. She’s the voice of reason, Etta Candy. And let’s call her Beth Candy, because I can’t call her Etta Candy anymore! [Laughs.] Our version was based on Rebel Wilson, who would be great as Beth Candy. And we were kinda thinking of Beth Ditto from the band Gossip, as well.

Speaking of supporting characters: You made Wonder Woman’s usual love interest, Steve Trevor, a black man. Why do that?

Partly because, honestly, quite simply and aesthetically, original Steve Trevor seemed such a milksop kind of character. Another blond, blue-eyed man at this point just seemed unacceptable in this age of diversity and representation.

You’ve said that you tend to put a lot of your personal issues and struggles into your superhero comics. What parts of yourself went into this one?

A lot of stuff happened over the time [I was working on it]. My mother died, for one. There’s an old lady who dies in the book and that was obviously exactly happening at the time, so it went straight into the book. But having gotten to the end of doing Batman and the Superman comics, I was kinda into this idea of talking to and about all the women in my life again. [Laughs.] Because I’d gotten away from writing boy’s-adventure fiction and suddenly, [I got] the chance to do Wonder Woman, to try and do something a bit different.

In the book, every time it looks like there would be a fight in a Batman or Superman comic, that’s not what happens. Diana subverts the fight. She turns it into something else. She uses the weird rituals of her culture to change things. It was finding a different way to tell the story and I found it quite exciting. Thinking about the women in my life and trying to tell a story that I thought they might find interesting. My mother and my sister, their relationship is there in Hippolyta and Diana. The relationship of my wife with her mother. [Laughs.] There’s a lot in there.

What advice would you give someone who’s tackling a Wonder Woman story?

I hate being a voice of authority! [Laughs.] Study the source material. The next book here — and I’ll get back to your question — but the next book here is gonna go into some of the more exotic stuff in the early Wonder Woman material. They used to do all kinds of stories about weird, winged women from space and underwater societies. We kinda liked that idea. The Earth One books are ostensibly set in an almost-convincing facsimile of the real world. But we wanna get into the weirdness of that culture.

So my advice would be, study the original material and also make yourself as familiar as you can with the rest of what’s been done with the character. Because there have been so many different interpretations. There’s always a different one. The new generation will be the film interpretation and that will be Wonder Woman for a lot of people. So this, again, is just a little facet of the jewel that is Wonder Woman, to have a look at and think about.

It’s so weird that there are no canonically definitive Wonder Woman stories in the way that The Dark Knight Returns is for Batman or your All-Star Superman is for Superman.

I guess it depends on who you are. Everyone’s got their favorites, but there isn’t a Dark Knight kind of book for Wonder Woman. I’m not trying to position what we’ve done as anything like it. I think it goes back to that no one’s really addressed the origins of the character and the really strange feelings that drove that character.

Throughout the time of representations of Wonder Woman have been quite strange. In the ’50s, she was actually just chasing Steve Trevor and constantly mooning over the fact that he wouldn’t marry her. Then in the ’60s, she was kinda lost and wearing a white jumpsuit and trying to find herself again in the counterculture. In the ’70s, she was trying to get re-admitted to the Justice League of America and be a superhero again. So there’s always been this strange progression of it and you have to join in and become a little part of that chain. The chain, of course, is the ideal metaphor here. [Laughs.]

Any closing thoughts on Wonder Woman and the project?

Hopefully, people like it! [Laughs.] I’d hate for people to be distracted by elements that could seem to be controversial. We’ve tried telling a decent story with all the weird twists and turns that activates the dynamic of Wonder Woman again and makes her a warrior for peace. My dad raised me a pacifist, so if I can make Wonder Woman a warrior for peace again, I’ll be quite happy.