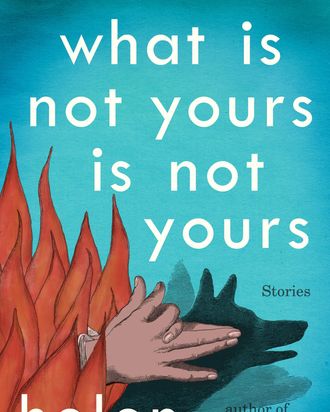

A restless imagination harnessed to a smooth and propulsive prose style — Helen Oyeyemi’s fiction is a juggernaut, and she brakes for no one. Her sentences have an elegance often set off by jolts of contemporary vernacular. “He was handsome but the scent of his cologne was one she very strongly associated with loan sharks,” she writes in “Drownings,” a story in her new collection, What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours. “Even so, can’t loan sharks also be caring boyfriends, or at the very least great in bed?” At the age of 31, Oyeyemi has published five much-laureled novels — beginning with The Icarus Girl, which she famously wrote in high school — and two plays. Magic comes cheap in fiction, but with Oyeyemi, you get the sense that it’s in her writing because reality isn’t enough for her. What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours is her first batch of stories, and like the rest of her work it partakes promiscuously of mythology, fairy tale, and folklore without turning a blind eye to the modern perversities of smartphones, YouTube celebrities, and electronic cigarettes. Oyeyemi was born in Nigeria and raised in London from age 4, graduated from Cambridge University, bolted the Columbia M.F.A. program after a semester, spent her 20s roaming Europe, was named one of Granta’s “Best Young British Novelists” in 2013, and is presently teaching in Kentucky. If her résumé gives the sense of an uncontainable talent, her full-throttle paragraphs confirm it.

But her new book leaves me with profoundly mixed reactions. The book has nine stories, though the number is misleading: Each is a nest of fictions within fictions. Before looking up her early reviews, I’d written in my notes, “Dizzying. Dazzling?” I wasn’t surprised to see that Robert Wiersema, in the Toronto Star, had deployed the same two words without feeling the need to qualify the second with a question mark. For Michael Schaub of NPR, the book is, “in a word, flawless.” But as the critic Aaron Bady remarked on Twitter, “flawless” seems just the wrong word for Oyeyemi, because she’s always “telling stories *wrong,* reminding you of what those stories … can’t reveal or tell.” What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours reminded me as well of James Wood’s remark, about Don DeLillo’s Underworld, that “it produces its own antibodies and makes criticism a small germ.” Oyeyemi’s talent is evident on every page — a talent so obvious that it invites critics to throw both hands up and say “Flawless!” — but it can also seem as if every page introduces three new characters, and a lot of them are disposable.

Of course, that very disposable quality is certainly part of the point, and the pleasure, of Oyeyemi’s fiction. It wouldn’t do to complain that The Decameron is overstuffed and uneven, and the same can be said of What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours. But it’s still hard to separate what’s gripping from what’s distracting in this book. I found myself most frustrated when it seemed Oyeyemi had hit on a brilliant conceit, then tossed it aside. The narrator of “ ‘Sorry’ Doesn’t Sweeten Her Tea,” for example, works in a spa where clients lose weight by entering a drug-induced coma for three days, fed by IV with a vitamin serum, and leave a size slimmer. But this intriguingly screwed-up workplace fades into the background when the story veers toward everyone’s fixation on a celebrity’s assault scandal. I didn’t sense a thematic connection between the story’s multiple strands (there’s also a fish, a shaman, and a witch or two), yet I wouldn’t deny its cumulative force. This isn’t quite true of every piece in the book. The nested stories in “Books and Roses” are connected by two keys that gain two characters entry to a rose garden and a library, but their tales dwindle in energy as the story goes on. My marginalia got a bit cruel: “Another fairy-tale-ish mini-story with an eerie, morally ambiguous ending. Next!”

It’s tempting to argue that Oyeyemi’s stories succeed when she maintains a constant grip on the reader’s attention, but it wouldn’t be accurate. “Drownings” has too much action and too many characters to keep track of. One almost feels taunted by Oyeyemi, at times, and suspects the story’s title to be a joke about its deluge, or swamp, of narrative detail. (The book’s epigraph, “open me carefully,” written by Emily Dickinson on an envelope that contained one of her letters, seems less a warning than a dare.) Then the story hits on its central image: A tyrant who’s been drowning his subjects attempts to immolate his bride on their wedding day, but by some supernatural means she’s inflammable (actually, she burns but doesn’t die or seem to feel it), she kills him by embracing him in her flaming arms, and when he tries to put himself out by jumping in the swamp, the ghosts of the victims of his drownings toss him back to dry land, where he burns, “roasting to death while his bride strolled back toward the city, peeling blackened patches of wedding dress off her as she went.” Not an image that’s easy to forget, and a good example of the darker side of Oyeyemi’s sensibility. By contrast, her trips to rose gardens — the prose gathers perfume — and libraries — books take on a fetish quality — swerve into the sentimental.

I doubt that Oyeyemi, also an accomplished critic, much minds being called sentimental. I can’t recall encountering fiction where portentous symbolism and a dry ironic sensibility sit together so easily. In another of her great dark moments, in “Is Your Blood As Red As This?,” a puppeteer walks onstage to the tune of TLC’s “No Scrubs,” and then his puppets all turn in their seats to reveal their throats have been slashed and their internal strings severed (this in a scene narrated by a fellow puppet), causing him to faint. One story, “Presence,” has a veneer of domestic psychological realism but turns creepily and satisfyingly into a science-fiction ghost story, something like Solaris except set in the leafier sections of London. Oyeyemi’s quieter mode points up the deliberate way she opens her other stories to something close to narrative chaos.

The quieter final third of What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours includes a slight comic retelling of the “Little Red Riding Hood” tale and a few nods toward the possibly autobiographical (one story is set at Cambridge). A few characters from earlier stories reappear, and there are a few images as striking as the flaming tyrant and the slain puppets (a man with a steak knife sticking out of his chest and blood dripping from the wound is observed using a pay phone to call to say he’ll be late for dinner and then to ring up an ambulance). There are enough recurrences to suggest a larger design submerged beneath all the hectic storytelling, and the appealingly blunt title points to obvious themes of deprivation and abundance, possession and loss, authenticity and appropriation. Oyeyemi is a prodigious and idiosyncratic talent finding her form in public, and What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours is something more interesting than a flawless or coherent book.

*This article appears in the March 21, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.