One would be forgiven for supposing that a good number of Pride and Prejudice adaptations exist for the express purpose of getting Darcy naked. Take this, from the romance imprint Clandestine Classics’ 2013 reboot of the cherished 1813 novel:

“ ‘Tell me you want me,’ he demanded. His voice was a deep rumble, husky and full of the promise of what was to come. ‘Tell me what you want from me.’

“Elizabeth brushed aside all lingering reticence and held his gaze as she replied. ‘I’ve never desired anything in my entire life as I desire you now. I want you inside me. I need it more than I need air.’ ”

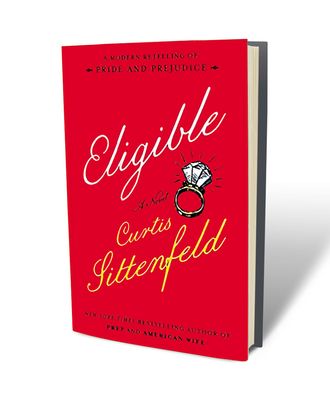

And here is how Eligible, Curtis Sittenfeld’s “modern retelling” — and the fourth of six books commissioned by the Austen Project in honor of the lady author’s bicentenary — imagines the scene:

“All in all, the experience [of sex between magazine writer Lizzie Bennet and neurosurgeon Fitzwilliam Darcy] was highly satisfying, certainly for her, and judging by external clues, it seemed reasonable to conclude for him as well; without question, it was far more enjoyable than prom night with Phillip Haley or most other couplings she’d partaken of in the 20 years following.”

Such circumlocution is not, on its face, the stuff of erotic fantasy. The narrator’s restraint and remove threaten to obscure what she is describing: hate sex between a shiny-haired young woman and a man so perfectly muscled “he was practically sculpted.”

And yet the passage remains, in its winking primness, extremely romantic. What unspeakable passions must heave beneath such reticence! How like Austen herself to want things both ways!

Lizzie and Darcy have been coming together for 200 years — sometimes explicitly, as in Death Comes to Pemberley, a PBS mini-series inspired by P. D. James’s best-selling murder mystery, and sometimes under more delicate euphemistic cover. What is wrong with us? What charge could we still get from envisioning these characters, or even their modern versions, doing it?

Sittenfeld has performed the trick of inhabiting preexisting personalities before; her third novel, American Wife, was written from Laura Bush’s perspective. With her Pride and Prejudice commission, she’s scored the plummiest of the Austen Project assignments. She roots the story in her own hometown of Cincinnati. Lizzie Bennet pens snappy profiles for Mascara magazine. Eldest sister Jane Bennett teaches yoga. Gorgeous, shallow Kitty and Lydia Bennet are obsessed with CrossFit. Chip Bingley, best known as the star of a Bachelor-like reality-TV show called Eligible, is single, in possession of a good fortune, and subject to certain axioms you may have heard of.

Sittenfeld mimics Austen particularly well (they share a wry and perceptive temperament), but as I’ve pointed out, she’s hardly alone in attempting to do so. Austen plots occupy the same niche as Shakespeare plays: They are rich, flexible narratives that form the backbone for countless cultural products. Consider that Pride and Prejudice alone has received upwards of a hundred book adaptations, including Pride and Platypus, Steampunk Darcy, Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, and a great many “erotic continuations.” There is the six-hour BBC mini-series starring Colin Firth, the 1940 film with Laurence Olivier and Greer Garson, and the 2005 remake that sent Keira Knightley flying across the moors.

This profusion is not terribly surprising. Austen’s themes, summed up in her titles — pride, prejudice, sense, sensibility, persuasion; which is to say, money, gender, class — are in no danger of falling out of fashion. What’s more, her work has a nimble, charming irony evident in both dialogue and the narrator’s mischievous turns of phrase; artfully simmering social tensions; real talk about the financial stakes of the dating game; and wonderfully vivid and flawed protagonists. But how many times can Darcy make the same patronizing marriage proposal and then craft the same dreamily elucidating apology letter? You sense, in the endless churn of Austen iterations, something as simple as the fannish desire to keep a beloved property going.

But is there something else we’re after? C. S. Lewis praised Austen for her mastery of the “undeception,” or epiphanic moment. She excelled, he argued, at bringing the era’s “great abstract nouns” — reason, vanity, fortitude, folly — suddenly to bear on her character’s lives. These revelations were necessary to her project because without norms and principles, “nothing can be ridiculous.” If Austen’s comedy flowed from her morality, then maybe our borrowings and updates show us yearning for ethical certainty. The stranger and less certain our relationships become, the more sway Austen has.

Or maybe it’s the swoony romance — the tease too potent to resist — that begs writers to portray that which Austen could not. The wish fulfillment in Pride and Prejudice runs deep. Darcy: powerful, wealthy, handsome. Elizabeth: loyal, clever, just imperfect enough. And Austen is such a discreet writer, all sighs and stolen glances. The prospect of lifting the curtain on her characters’ sex lives is too delicious to discount.

If Austen’s restraint suggests treasure left beneath the surface, the paradoxes she sustains in her writing keep us from feeling as though we’ve figured her out. Who but she can conjure such ardencies in readers while remaining so pragmatic and demure? Who else splices so much light-fingered subtlety with so many fervent (and occasionally cruel) opinions?

Austen invites a sort of playful uncertainty when it comes to her own books. (“Till this moment I never knew myself,” Elizabeth says, and the novel insinuates that there is always more to know.) Along with her tendency to understate, such a gently subversive mind-set might encourage elaborations and redos. But I don’t believe Austen’s irony or skepticism provides a true answer to the adaptation question.

No, her magic is looser and lovelier than that. I was recently reading the billionth article about women choosing their choice because we can’t have it all when it crept up on me — the undeception. In this charmed Janeian space, where paradoxes resolve and impossibilities unravel, two contradictory things were true: People are terrible. And I would find happiness. At the same time, I was wise: I perceived how hamstrung I was by fellow humans and my own blinkered pride. I was a feminist who longed to be escorted to the ball in a dazzling dress. I murmured nasty things about my friend’s sister and was thought alluringly impertinent, not mean; I had great sex forever and ever with a smitten representative of the very social codes that threatened to ensnare me. Very little of it made sense, and yet it all worked out because someone, behind the scenes, was putting words together so fervidly, so intelligently, that her vision became irrefutable.

And then the spell broke. I realized I could have it one or the other way, but not both. So I went back to Pride and Prejudice. “It is a truth universally acknowledged,” Austen insisted, that what you desire also miraculously turns out to be what the universe desires for you.

Which is to say, with all the necessary updates and substitutions for 2016: Your happy ending awaits.

Curtis Sittenfeld’s Austen-inspired Eligible is out April 19.

*This article appears in the March 21, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.