One of the truisms of the recording industry is that the powers that be will always resist technological change. When George Martin, then in his 20s, joined, in 1950, the British giant EMI, the biggest and grandest record label in the world, he was a classical music aficionado and one of no little talent. Back then, records were vinyl platters that played at 78 revolutions per minute and lasted a maximum of four minutes and 15 seconds. A typical piece of classical music, then the central product of the industry, was divided up into musical chunks of that size, and technicians like Martin would split up, say, the movement of a symphony, sometimes crudely duplicating chords after the switch-over to give listeners a reminder of where the melody had left off.

Not long after, a new technology emerged: the LP record, which could last 20 or 30 minutes, allowing classical music fans, for example, to hear a full movement, or even two, of a symphony. EMI was adamantly opposed to it, consumers be damned, and over the first half of the 1950s it lost its dominance of the U.K. recording market.

This was a lesson not lost on Martin, and was a major part of what became a charmed life for him, one that he graciously acknowledged was driven at key points by the machinations of a fairy godfather completely unrelated to his natural talents.

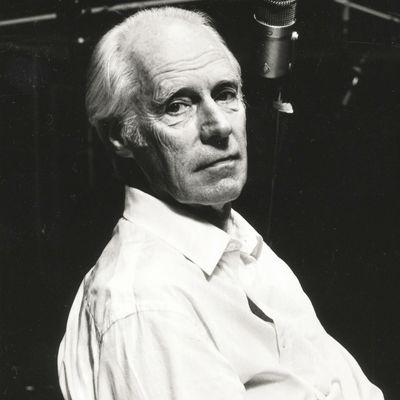

Martin came of age precisely when a medium perfectly suited to his sensibilities came to the fore: electronic recording. He was old enough to slipstream into one minor cultural revolution (British comedy in the 1950s) and yet just barely still young enough to hitch a ride when that major one — electronic recording, arguably the definitive one of the century — emerged. He fell into those things through a patchwork of coincidence, luck, mettle, and (that word again) talent. He could discourse on Ravel (his favorite artist), Bach, electronic microphones, tape setups, pop music, and record-industry machinations even as his patrician mien eventually made him the friend of stars and royals.

Martin was 90 when he died, last night, a connection to a time distant to most of us. Despite his outward urbanity he’d come from a poor family, growing up without electricity, or even a kitchen, in a tiny apartment in North London. Even members of the Beatles had grown up without indoor plumbing, children of a land that had taken the brunt of the effort to stop Hitler. Martin, of course, was just shy of a generation older, and only by chance was not a potential victim of the war himself — he’d volunteered to be a pilot, but by that time the U.S. had dropped atomic bombs on Japan, and the war was on its way to being over. In his memoir, All You Need Is Ears, Martin casually mentions flying off aircraft carriers; with nothing like modern navigation systems, pilots would take off, fly for hours, and then have to find their way back to the ships through their own sense of navigation. “The result of failure in this enterprise was obvious,” he wrote.

Martin had taught himself to read and write music, and after a time of living, along with his first wife, at his parents’ after the war, he made a living at it. Through the intervention of that fairy godfather, he was summoned to a division of EMI to be an assistant to the subsidiary’s president. This was Parlophone, the conglomerate’s backward and forgotten cousin. (The president, as it turned out, was essentially its only employee.) But Martin learned for five years, and then was rewarded the top position himself. He made the label a lot of money by delving into a new world of manic British comedy, and recorded “The Goon Show” and Peter Sellers, among many others. You can hear in this hit he made with Peter Sellers and Sophia Loren the tastefulness and dry wit he brought even to a novelty record:

The man who’d orchestrated and recorded symphonies was now playing with the so-called “wobble board,” which made the high-larious popping sound on the Sellers track. Martin could do anything. Bach, he wrote many years later, had 20 kids and wrote incessantly for decades; he was, Martin noted approvingly, “a worker and a craftsman.” Martin himself, juggling everything he could to keep little Parlophone afloat, was correspondingly open-minded when, after some internal machinations, he was confronted in the studio by a band that had been turned down by virtually every label in the land.

It was love at first sight, Martin said later.

He found the four young men in the band charming. He couldn’t figure out which one was the group’s leader — all bands at the time had a leader — but decided to let it go. John was manic and Paul was quite pleasant. The guitarist George wasn’t as talented as the other two, but not bad. The drummer was quite a looker, a not insignificant factor at the time, but simply couldn’t play well enough. He pulled the others aside and told them Pete Best had to go. This was fine — they already had their eye on another friend from Liverpool, Richard Starkey, known as Ringo.

It was a time when producers and musicians wore coats and ties, and engineers white lab-coats. Assembled in the studio, Martin heard … something. More than anything else, he had ears that could hear what others couldn’t. He knew why the band hadn’t been signed by producers at the country’s many tonier labels: “They couldn’t hear the music for the noise.”

Martin may have been talented musically; his genius socially was to find in this disparate group a sound and a purpose, and guide their natural talents to a place in history. Such phrases are overused in the Age of Kardashian, but any sober observer will attest that the world pre- and post-Beatles was very different indeed.

The Beatles had assets that were simply inconceivable at the time. Paul McCartney would become one of the greatest pop songwriters of the century, and possibly the greatest — beating Irving Berlin on points, and in sophistication and class up there with Gershwin and Porter. He was also adorable to look at. In Lennon, the group had another very significant pop songwriter, and, if I can make this distinction, one of the very greatest (Dylan, not too many others) rock songwriters. Harrison was a decent and valuable guitarist and would contribute a few classic songs to the band’s repertoire, and in Ringo they ended up with a steady and distinctive drummer.

When Lennon and McCartney were asked by Martin for some original songs, they brought in two so-so ones — “Love Me Do” and “P.S. I Love You.” From the first, Martin invited the members into the control room, to ask them what they liked and didn’t like in the recording. (“I don’t like your tie,” Harrison told him.) Asked to bring in more, they produced indications of what Martin immediately recognized was astonishing growth, including “Please Please Me” and “She Loves You.”

For the latter song, Martin created an appropriately explosive beginning, which hailed a new sound and era. After a first album filled out with covers, the band began to scale upward from there, into pop hit after pop hit after pop hit (“I Want to Hold Your Hand,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “A Hard Day’s Night”), to classic after classic after classic (“Help,” “Yesterday,” “Ticket to Ride”), and then to one cultural-firmament-shaking landmark after another (“Strawberry Fields Forever,” Sgt. Pepper, “Hey Jude,” The White Album, Abbey Road, etc., etc., etc.).

There was always experimentation and open-mindedness, but the experimentation was in the service of pop. And if the pop world was an Inferno, Martin was a Virgilian figure to the four young men — in various senses their leader, their teacher, their master — and they indeed were possessors of sprawling Dantean ingenuity in their own right. Martin would never have created the epochal “Strawberry Fields Forever” on his own. But the combination of John’s inchoate ideas and Martin’s studio virtuosity allowed them to seek together a corporeal, ultimately shattering manifestation of Lennon’s vision.

(YouTube has it taken down right now, but poke around for the “Strawberry Fields Forever” “edit take” from the Anthology collection to hear this dynamic in action.)

Even today, it’s hard to encapsulate everything Martin and the four members of the group did. Just as Debussy and Ravel, in Martin’s words, “painted with sound,” using the various instruments of the orchestra, he and the Beatles used a studio palette in a metaphorically similar, if technologically distinct, way. Leaving aside the catholic instrumentation (everything from strings to French horn to tabla dotted the group’s songs), voices and instrument were slightly sped up or slowed down; pieces of songs were taken apart, run backward, and stitched together; recordings were mixed down and compressed, and then mixed down some more; after years of dedication to mono (the only way to hear Beatles songs up to Sgt. Pepper), some stereo was experimented with. (And let’s face it, Sgt. Pepper is mind-blowing in stereo, too). Even the physical tape was manipulated and abused, and some variety or combination of all of this created the somehow organic, yet entirely electronic, magic that the five put down on record again and again.

Within a few years, the group had mastered the pop idiom, flaking these songs with variously technological innovations (like the guitar feedback at the top of “I Feel Fine”). Then came full-on experimentation, as on pastiches like “Tomorrow Never Knows” — even as they kept having hits with utterly commercial things like “Michelle,” “Eleanor Rigby,” and “Day Tripper.” The world is different now, but it’s worth noting that back then, besides the 13 or so (!) albums’ worth of material they released on formal releases over the band’s seven-year career, there was an additional absurd number of single tracks occasionally thrown together on compilation albums. The band produced at full speed for seven years, and yet from start to finish, and to this day, offered their audience only a handful of inferior tracks. With each of these, and then with Sgt. Pepper, an album that had no hit singles and forever changed the direction of pop music, the band did something few artists have ever done, which is essentially embody in itself the furthest reaches of the potential of that medium.

Martin in the 40-something years since the Beatles produced a variety of other artists and oversaw the Beatles’ recorded legacy. He left EMI in the mid-1960s to form his own production company (and thereby make more than a salary off the group’s recordings), but by his own admission was not a millionaire later in life. He was mostly this: a pop elder statesman, consorting with royalty and always retaining his air of goodwill, common sense, good taste, and unflappability.

He never took too much credit from the band, but never downplayed his own contributions either. He was patrician in his later years, sure, but at heart really a man who came out of a war to a broken society and helped create the world we live in now. He was a genius at guidance, collaboration, and creating joy through pure sound — a worker, you might say, and a craftsman.