One of the greatest disappointments in the history of filmed science fiction was 1993ÔÇÖs Alien 3. To be fair, it had a lot to live up to as the third installment in a beloved (and lucrative) franchise that began with Ridley ScottÔÇÖs white-knuckle Alien and continued with James CameronÔÇÖs slam-bang Aliens. But the third chapter was plagued by a lackluster script that killed off two of AliensÔÇÖ most beloved characters ÔÇö space marine Hicks and survivalist child Newt ÔÇö in the first few minutes and spiraled into muddy nonsense from there. It was the Godfather, Part III of sci-fi. (And the less said about 1997ÔÇÖs Alien: Resurrection, the better.)

Luckily, indie-comics fans had long been familiar with an alternative sequel, one that lived up to the horrifying promise of the first two films: Dark HorseÔÇÖs serialized Aliens comic, launched in 1987. It picked up a few years after the end of Aliens and chronicled the continuing adventures of Hicks and Newt. (Ripley was unavailable due to some licensing mishegoss.)

As of today, the 156 pages of unadulterated story are finally available in a gorgeous hardcover edition (there have been printings in the past, but they colorized the original black-and-white artwork or changed the leadsÔÇÖ names to ÔÇ£WilksÔÇØ and ÔÇ£BillieÔÇØ to awkwardly accommodate Alien 3ÔÇÖs continuity). For anyone who loves the Alien saga, itÔÇÖs a must-have.

Part of the magic of Alien and Aliens was the way the two movies used the same toothy, phallic monstrosities to explore different genres. ScottÔÇÖs masterpiece was a haunted-house story: A group of people are stuck in a claustrophobic structure and fight to survive while a mysterious specter of death picks them off. CameronÔÇÖs take was, by contrast, one of the all-time great action movies: A group of hardened soldiers go up against an unrelenting enemy horde with no hope of backup.

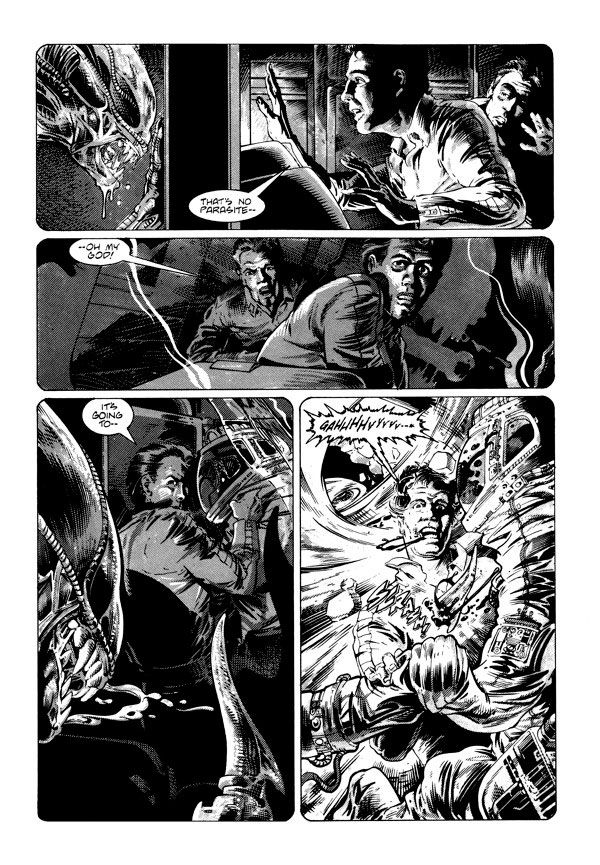

The comic ÔÇö penned by Mark Verheiden and illustrated by Mark A. Nelson ÔÇö incorporated yet another genre: Lovecraftian existential horror. Though it borrows its high-tech torturers and sinister corporations from the then-trendy motifs of cyberpunk, its philosophy and structure feel a lot more like At the Mountains of Madness than Blade Runner. The tone and themes are as bleak and terrifying as NelsonÔÇÖs stunning blacks and whites.

The plot details can get a bit wonky, but the basic arc is simple: Hicks and Newt, both suffering from PTSD, find themselves on a mission to the aliensÔÇÖ homeworld; meanwhile, Earth-based warmongers and religious fanatics rush to embrace the aliens for weapons patents or apocalyptic submission, respectively. Naturally, MurphyÔÇÖs Law sets in for all of these plot threads and the creatures end up infesting Earth.

The process is stretched out and chronicled in agonizing detail: We see humans with alien embryos inside them having horrific nightmares about their mothers being murdered by monsters; we see a montage of a plane passenger, a bikinied beachgoer, and a pleasant grandmother all perishing as aliens burst from their chests; we hear repeatedly that humanity was too craven and self-defeating to ever join together and make a stand. The leader of an alien-worshipping doomsday cult calls the monsters ÔÇ£the immaculate incubation,ÔÇØ and although Hicks and Newt do their best to fight some of them off, they eventually come to that same conclusion: The aliens are blood-curdlingly perfect.

Indeed, if thereÔÇÖs a message to the whole story, itÔÇÖs LovecraftÔÇÖs message about Cthulhu, Azathoth, and their otherworldly ilk: Gods are real, and they want to kill you. When Hicks and Newt make it to the homeworld, they encounter a different kind of extraterrestrial, one of the species that piloted the derelict spaceship Ripley et. al. discovered in Alien. Though itÔÇÖs extremely powerful and fights off some of the swarming creatures, itÔÇÖs far from benevolent: It sends Newt a harsh telepathic message (ÔÇ£something exploded inside my head, bright like a million sunsÔÇØ) to inform her that itÔÇÖs going to orbit Earth and simply wait for the aliens to kill off all the humans, at which point it can colonize the planet.

The only consolation is companionship, and our two damaged protagonists find it in each other. Their character beats are a little rote: Hicks spends a great deal of time blabbing tirades about corrupt bureaucrats, and Newt gets wrapped up in an extremely abrupt love story. But honestly, the human characters arenÔÇÖt where the action is ÔÇö the aesthetics are. VerheidenÔÇÖs storytelling is ambitiously bleak, NelsonÔÇÖs visuals are gruesome, and the combination of the two produced a nightmare-fueled comic unlike any other. ItÔÇÖs good to have it back.