I love momentum. I’m not a speed freak, and I can be thoughtful and procedural at times. But I like things to proceed apace. I’m like an 8-track tape you had to fast-forward but could never rewind. Characterologically, I’m always thinking: What is the next iteration, the next thing?

From the time I was young, I gravitated to art, but if you like art, you have to decide really quickly if you’re going to make art or you’re going to make art happen. And I knew very early that I wanted to make art happen. When I first moved to the city in the mid-1980s, living with six random roommates in a loft building on Grand Street and attending NYU, it was a quieter art world, much more accessible. I would go to openings, and it would be just 60 people standing in a room, having cheap wine in plastic cups and eating Triscuits. Some of my neighbors in my building were artists, like the photographer Marcus Leatherdale and the painter Stephen Lack, and soon enough I was meeting people my own age who were just starting their careers.

When I started out, I worked as a curator, but academics didn’t really suit my temperament. I was surprised to discover the thing I’m really good at: calling the market and risk assessment. Pricing a work of art, understanding its value, is an extremely proprietary skill. Very few people can do it. It’s what I did for almost 13 years at Christie’s and now as an art adviser whose business was recently acquired by Sotheby’s. A lot of people feel like the market is unkind, and artists will come and yell at me because their works are not selling, but here’s the truth: The art market is a living, breathing, organic thing, and you can only have limited control over it. The market is like the weather: You can complain about it or you can learn how to deal with it.

Later on, when I’m older, I’ll go back to school and write an economics dissertation on what determines the secondary market value of an artist. But that’ll be a long time in the future. Here are clues to how the art market is working right now:

1. Sometimes the Principle of Scarcity Doesn’t Apply

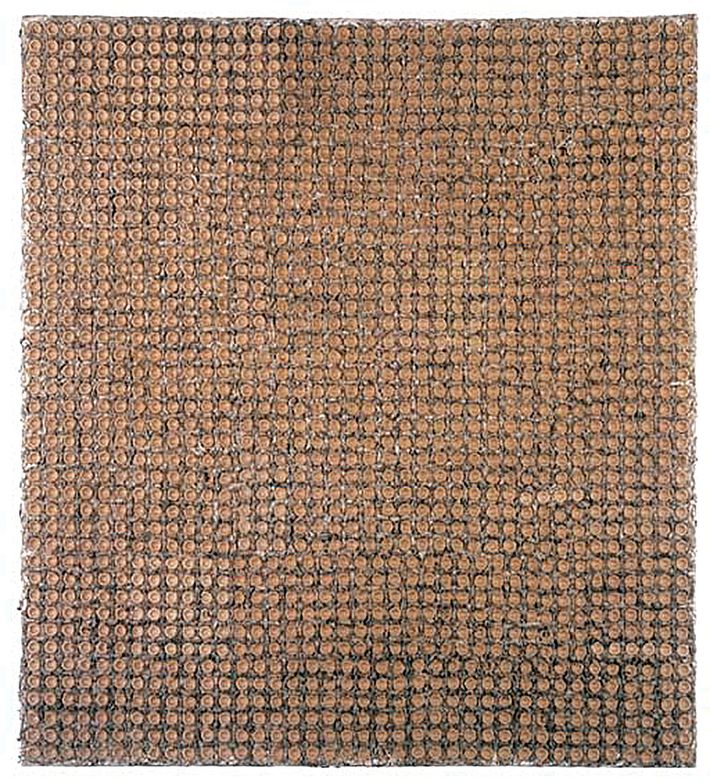

Artist: Gerhard Richter

Title: ‘Abstraktes Bild (809-4),’ 1994

Sold for: $34.2 million in 2012

Often, the value of an artwork contains a straightforward calculation: Rare objects are valuable. Jackson Pollock is a scarcity market. If there’s one thing I dream about selling one day — something so rare that it would truly have a price beyond imagination — it’s a Pollock mural. There hasn’t been a proper Pollock mural on the market in ages.

Other times, the law of supply and demand works in contrary ways. The classic example is Andy Warhol, whose prints are like units of stock. They can go up or down slightly based on mood or the number of people building new homes and decorating, but they have completely predictable values. And so in a case like this, it is to an artist’s advantage to have a very large, organized, and actively traded body of work.

Gerhard Richter is another interesting example. He is one of the greatest living artists. One of my favorite things to see at the MoMA is his cycle of black-and-white photo paintings about the Baader-Meinhof gang — it gives me the chills. That’s the work that academics love. But what the market currently values are his abstracts. Richter made around 3,000 works of art, of which 2,200 are abstracts. So, not exactly rare, but the abstracts are stunning on the wall. A few years ago, a Richter abstract, previously owned by Eric Clapton, set the auction record — since surpassed — for a living artist. So the theory is that they have become icons of global taste, of style and sophistication, and of wealth. They are valuable because they are expensive, and the more there are, the more the market wants.

2. A Well-Timed Auction Can Launch a Career

Artist: Yayoi Kusama

Title: ‘No. B, 3,’ 1962

Sold for: $1.2 million in 2005

Artists are not always the best judge of their work or the best shepherds of their career. Often it’s the market that understands the art’s value. Yayoi Kusama, for instance, didn’t make moves that would today be perceived as savvy career management. (She moved from New York back to Japan in the 1970s and checked into a sanatorium.) For most of her career, she was in the doldrums — she had a very sluggish market. When I was at Christie’s, a cache of material from her original New York dealer came to market in 2005. The work was sensational. The best of them went to auction at an evening sale — a risk, since performance on the evening-sale stage is a test for any artist. But a piece sold for nearly $1.2 million. Larry Gagosian then picked her up, the Tate and the Whitney did retrospectives. She’s since collaborated with Louis Vuitton on handbags. That is more of a design exercise than an art exercise — but it increases her brand recognition. And the point is that this revival was all precipitated, to a large degree, by some action in the marketplace.

3. Youth Sells — If the Right Old Collectors Buy In

Artist: Tauba Auerbach

Title: ‘Crumple IV,’ 2008

Sold for: $1 million in 2014

A young artist is like a young athlete — it’s easier to be young than old because the marketplace likes newness. Tauba Auerbach is still only in her mid-30s, but there is a consensus among the collector community that she is for real. You can feel it. Right from the beginning of her career, her work was very, very well placed with the kind of collectors who can influence the market simply because they bought it. Collectors are not created equally. Dakis Joannou had her work very early, as did the movie producer Michael Lynne — they are fantastic smellers of early talent — and others who were known to be very good at picking. Being recognized by the right collectors can matter more than a major museum show, which can affect the market more when it’s still a rumor than when it’s news or when it happens.

Even though Auerbach has a market that is only about five years old, she seems like she will be a constant force in the market to come. She works in the language of abstraction, which means she’s part of a lineage (one that is easy on the eyes); she is from San Francisco, and there is something about her work that is evidence of digital culture in our midst, and she is very adept at moving paint around. Also, unlike artists who use mass-production techniques, she works by hand, which means you won’t have a problem of there being too much inventory. In her case, keeping it finite is key. An opposing example is Damien Hirst: He had a big sale of his work in 2008 that made a lot of money, but now there’s a perception of too much material out there. Not every artist is like Warhol or Richter. And there’s always a danger when your work goes into production of it being conflated with a design object. With Auerbach, there’s something about virtuosity that we like — simply that it looks like it took a long time to make.

4. The Market Likes What It Understands

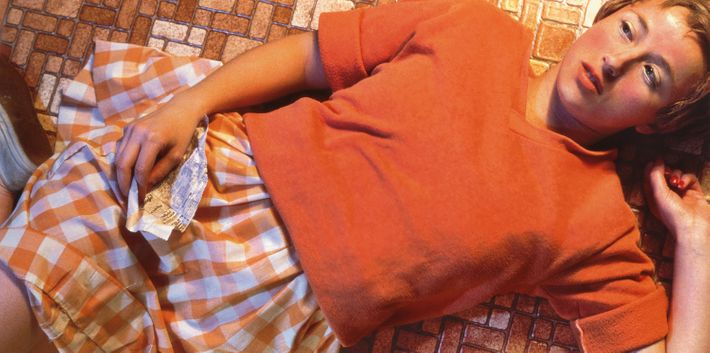

Artist: Cindy Sherman

Title: ‘Untitled,’$2 1981

Sold for: $3.9 million in 2011

I occasionally tell beginning collectors, novices who are looking for undervalued properties, that they should focus on female artists, because a lot of women are now benefiting from corrections in history and the marketplace. On the wall of my office, I have a series of six photographs by the artist Ana Mendieta, called “Self Portrait With Blood.” When I was coming up in art world, she was little known, most famous for being allegedly tossed out of a window by her husband, sculptor Carl Andre, who was then acquitted of her death. I just love her work — she was a proto-performance, sculptural, edgy feminist artist who worked in many media.

Cindy Sherman is benefiting from the market’s awakening as much as anyone. One of her Centerfolds was sold at Christie’s for what was at the time a record for a photograph. It had an excellent consignor in Robert Rosenblum, the famous historian and art collector. The estimate was $1.5 million to $2 million, and it made $3.89 million. The consensus had been that it was an iconic Sherman: The photograph had been used on a book cover and on posters and bus ads around the world, and others in the edition were in museum collections. She’s lying there in an orange sweater on a linoleum floor and looks like a dreamy girl. It’s everything you wanted Sherman to say; it had an air of innocence and uncertainty.

Sherman’s a good example of how the market likes what it knows — it likes when work is understandable. After 40 years of production, Sherman is known for doing certain things. Some bodies of work are champions, others less so. It was hard for the Beatles to be un-Beatles-ed, too. Once you’re known to be good at something, the world doesn’t always let you experiment as you might like. So the Sherman market looks like a flight of stairs — it plateaus, then new buyers enter, it goes up, then they get sated, then new buyers discover her. A single show won’t change her prospects because she’s so solidly written into art history.

5. The British Empire Still Reaches Far

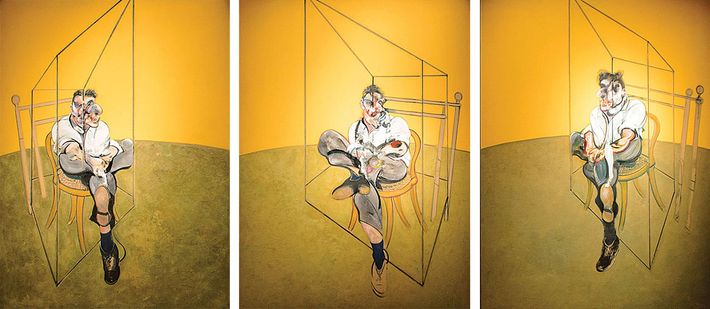

Artist: Francis Bacon

Title: ‘Three Studies of Lucian Freud,’ 1969

Sold for: $142.4 million in 2013

In the postwar years, when the crown of the art world moved from Paris to New York, there was American suspicion about Francis Bacon. We were the place of daring innovation, where artists were swashbucklers, while Bacon was working in the figurative-portrait tradition, doing something new with something old. It looked traditional. But the Bacon market is now so strong for two reasons. First, Americans are admitting that we were wrong — he was an absolute genius, and we missed this for no other reason than ethnocentrism. And second, he is hugely popular among people who were educated in Britain, studied Bacon in an art-history class, and then went back to their well-to-do families in the Middle East and Asia. They believed Bacon was great because (a) he was great and (b) they were taught that he was great.

The globalization of the art world is real and likely to only increase. Instead of putting millions into boats and cars, you can invest in something culturally relevant and possibly beautiful, which is also a pretty safe and discreet repository of wealth. I’m an expert in an esoteric asset class that happens to be an excellent reservoir of value. Some days I think I’m in the alternative-currency business.

*A version of this article appears in the April 18, 2016 issue of New York Magazine.