Depression is often a disgusting business. It’s partially defined by absences — lack of social contact, of energy, of joy — but it’s also crawling with hideous presences: the odor of half-eaten takeout food, the stains of unlaundered clothes. If you have a fondness for weed or booze, the list grows to include ash, drooling bottles, and persistent headaches.

Depression is tactile. It’s sweaty. It leaves a slime trail. All too often, narratives about it make it seem lonely and sterile — but not so with writer/artist Simon Hanselmann’s masterful collection of miserable comic strips, Megg & Mogg in Amsterdam (and Other Stories). It stinks, and I mean that as a compliment.

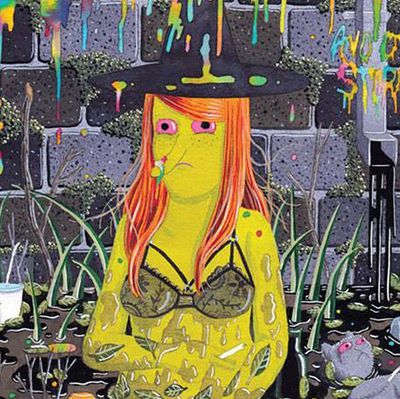

Hanselmann’s last book of comics, 2014’s Megahex, wound up on a slew of best-of lists, and this new volume deserves similar acclaim. As in Megahex, this comic consists of short, bleak episodes in the lives of a group of compatriots in an unnamed city. I suppose you could call them friends, but they’re mostly just horrible to each other. The titular Megg and Mogg are a witch and a chubby little cat, respectively, and they’re sort of a couple — their relationship seems to consist mostly of smoking pot, halfheartedly screwing, and insulting other people. The object of their verbal (and, occasionally, physical) abuse is their roommate, a generally decent owl named Owl, whose primary crime is not running away from his living companions at top speed.

This trio’s dynamic and Hanselmann’s approach to comedy are pretty well summarized in the new book’s first strip, “Chain Eaters.” Megg and Mogg are sitting on their couch, each eating their own entire pizza. Megg groans. “Fuck … my head’s spinning …” she says. “I need more Red Bull.” She guzzles it, smokes, then lazily makes out with Mogg, drool and grease hanging between their mouths. Owl comes home from work and is horrified that they’ve eaten pizza seven nights in a row. Mogg, irritated, points out that “it’s actually the morning for us, Owl. Get it right.” “I’m seriously amazed that you guys are still alive,” Owl remarks, his eyes wide, before Megg and Mogg abruptly fall asleep. “How can you sleep after drinking this much Red Bull?” Owl exclaims in the final panel. “Fucking horrifying.” Those two words feel especially potent because they’re presented as a kind of punch line.

That three-character interplay is compelling enough on its own, but readers soon learn that it’s just a prelude to the introduction of the book’s breakout star, Werewolf Jones. A wolfman and perpetual hanger-on of the core cast, his life is the most reprehensible of all. He cheerfully takes ketamine and heroin when he’s not giving his friends STIs or weeping over his ruined life. He’s also the father to two near-feral tweens whom he plies with Monster Energy Drink and marijuana. He’s like the proverbial car crash you can’t stop looking at, getting more insane with each passing appearance. By the time he’s trying to smuggle his kids onto a flight by knocking them out with pills and stuffing them in duffel bags, he’s somehow gone past monstrousness and into filthy tragedy.

Hanselmann’s simple and cartoonish artwork makes this all look goofy, and the aforementioned setup/punch-line structure makes things seem like they should be funny, though it’s mostly just jaw-droppingly grim. There are a fair amount of black-hearted laughs, to be sure — like the time Megg and Mogg go to a couples’ therapy appointment, only to find that the therapist may or may not be in the midst of an orgy. And there’s something amusingly entrancing about how over the top everyone’s abuse of Owl can get: At one point, he tries to escape an especially insane situation at the apartment by checking into a hotel, only to have Werewolf Jones track him down and smash through the room’s door in an awe-inspiringly misguided attempt to apologize for being a dick.

But the collection’s power lies in the way it shows how much we can destroy our relationships with others and with ourselves when we’re emotionally spiraling. Hanselmann has a tremendous amount of empathy for these characters, showing them to us at their most vulnerable and making it clear that they have such deep dysfunctions that they have no idea how to break the cycle and become healthy. Hopefully readers won’t be able to totally relate to their awful lots in life, but that dreadful sense of being trapped in self-perpetuating mental traps should be familiar to anyone who has been in the viselike grip of depression, anxiety, or addiction. When Megg and Mogg take their titular journey to the Netherlands and utterly fail to escape their own miserable heads, I felt my chest tighten with recognition.

This feels like the part of a review where one says there are a few glimpses of hope and goodwill in the book, but there really aren’t. That’s a virtue. The world already has a sufficient supply of narratives about mental health that say things get better, so there’s something strangely powerful about one that has no such cheerleading. Like listening to a sad song during a breakup, reading a miserable book during a difficult time can be comforting. Megg & Mogg in Amsterdam doesn’t talk down to you. It gives you one of the oddest, most powerful reassurances of all: It tells you you’re not alone in your misery.