As told to New York Magazine senior editor Jesse Singal. Original photography by New York Magazine photographer Konstantin Sergeyev.

I didn’t even think twice about performing in North Carolina two weeks ago, on Sunday, May 15, in Durham. I’m not a resident of North Carolina, but I do work in the state — my band has played there at least once or twice a year for almost the past 20 years, and I pay taxes in the state. If you’re a trans person living in North Carolina, it’s not like you have the option to be like, You know what? I’m gonna boycott my state — I’m not going to work today. I’m not gonna shop at the store. So my solution was never gonna be, I’m just not gonna play in North Carolina. That’s ridiculous. I love North Carolina. It’s a beautiful state.

Things did feel different before the show, though. There was a charge in the air. I definitely may have been having panic attacks every half-hour. At times, my mind was even jumping to the fear of What if a crazy comes to the show and tries to kill me? What if someone jumps up onstage and does something? What if someone targets the show? What if you’re endangering people? Those thoughts were real to me, and really, really terrifying. I was just hoping that everyone would be safe and nothing would happen because of the show.

The nerves started as soon as I got to North Carolina. Just driving into the state, stopping at gas stations, going where you go — I was on edge all day. I always wait until there’s a unisex restroom, because I’m afraid. I also don’t want to make people uncomfortable — my desire is to feel comfortable, but I don’t want to make other people feel uncomfortable either. If it’s a crowded public restroom, I know I don’t pass, and I know that if I walk into a women’s restroom, someone would possibly take offense. Maybe scream. Who knows? In North Carolina, with it being illegal, it was like, Okay, well, we’re going to wait until there’s a Starbucks, since Starbucks has single-unit bathrooms, and that’s where we usually stop. Which is ironic because I’m someone who wrote a song about throwing bricks through Starbucks’s windows.

Once I got to the venue, it was great: It had a smelly, dirty backstage, and there was a private restroom for the band. [Drummer] Atom [Willard] always gives a speech before the show, and it’s usually absurd and ridiculous. That night it was, “Here we are, we’re in North Carolina, we’re gonna go play a good punk-rock show, it’s gonna be a lot of fun. Everybody say ‘RIBS’ on three.” And we yelled out “RIBS.”

It’s just pure adrenaline when you start playing your first song at a show — the best high in the world. I live for it. It’s what I was born to do. We started with the song “I Was a Teenage Anarchist.” Over the course of the night, “Transgender Dysphoria Blues” and “True Trans Soul Rebel” probably got the biggest reactions. Every single Against Me! record has songs that are me dealing with my dysphoria, and as time progressed I got a little more brazen about that. The title track from my third record, “Searching for a Former Clarity,” has the line about “Confessing childhood secrets/of dressing up in women’s clothes,” which was extremely autobiographical.

Then, the next record we did had a song called “The Ocean.” That song came to me all at once — I wasn’t really thinking about what I was writing, but afterward I definitely realized, Oh, shit — I totally out myself in this song. There’s no metaphor to the line “If I could have chosen/I would have been born a woman.” No metaphors! I remember asking everyone in the band, “Is this weird? Should I change the lyrics?” And everyone was like, “Nope, it’s fine. It’s cool.” Then after we did “White Crosses,” it turned into me being unable to write about anything else. Anytime I picked up my pen, everything that came out was overtly about gender. At that point, I think it was really my subconscious being like, You are going to confront this. This is happening.

I use songwriting as an outlet, a way to deal and to cope. It was gender dysphoria that led me to punk rock, so naturally I sometimes found myself writing about the feelings generated by what I was experiencing. At first I was scared of anyone finding out, so I’d be really crafty — or at least I thought I was being crafty — about disguising what I was talking about. We put out an EP after our first full-length album called “The Disco Before the Breakdown,” and the lyrics to the title track — “I know they’re gonna laugh at us/if they see us out together holding hands like this” — that’s just a metaphor for gender identity. Or the lines on “Tonight We’re Gonna Give It 35%”: “Can you live with what you know/About yourself/When you’re all alone/Behind closed doors/The things we never said/But we always knew were right there … ”

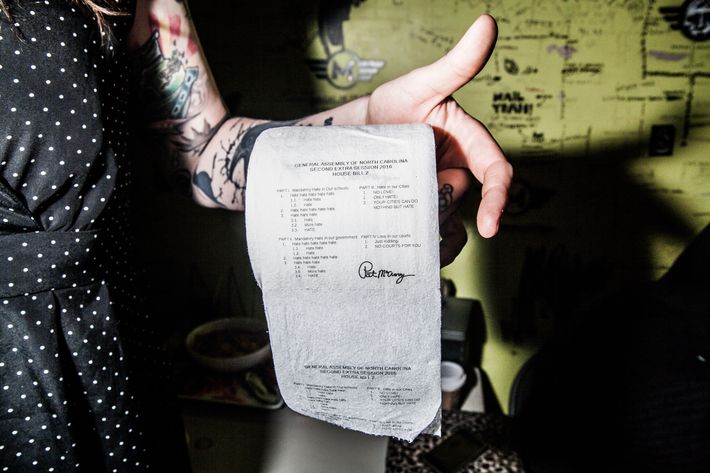

After the show I made a point of making myself available and hanging out, talking with people. Someone had printed the bathroom bill on toilet-paper rolls and put them at the venue, though they changed the wording to what it really is: “Part 1: Mandatory hate in our schools. Subsection 1: hate, hate, hate, hate, hate. 1.1: Hate, hate. 1.2: Hate … ” I met the person who had the toilet paper printed up, and we took a picture together. At that show in particular, there were a lot of younger kids — really young kids who are struggling with gender identity and struggling with that kind of discrimination. When I came out, I had no community. I didn’t know any trans people. So back then, to go on tour and immediately have people who would wait around after shows to say hey, to say they were there if I needed a friend — that meant the world to me.

I think a lack of education and pure ignorance led to the bill. It’s also oddly focused on trans women specifically, and the argument is predicated on the idea of transgender people being mentally ill, or pedophiles, or sexual predators, which is just absurd. If the fear is of sexual assault or rape, well, there are already laws against things like that. People have been using the restroom with transgender people all their life — they generally just don’t realize it.

Fighting that ignorance is why I put myself out there the way I do — and that was the point of still doing the show, and what is a gratifying part of touring in general now. A large percentage of our audience are gender-queer, queer, or non-conforming in one way or another. But then there’s a segment of the audience who aren’t, and who have had no interaction with people like that. They may be curious and may not know how they feel about it. Then they come out to a show and they realize, While I might not understand the trans experience itself, I can understand the feelings of isolation, of feeling like you don’t fit in, of being discriminated against. You realize the commonalities.

Before the show I set my birth certificate on fire in front of everyone. That was to emphasize the illogical nature of current laws. It’s one thing to say, “You have to use the bathroom that corresponds to your identification.” If that’s the case, I should be able to go, “Okay, well, tell me how I can change my identification.” But if you’re then telling me, “There’s no way you can change your identification,” that’s where it’s fucked up — you’re putting people in an unwinnable situation. In order to start hormone replacement therapy, which I’ve been on for about four years, I had to undergo months of intense psychotherapy and have a licensed therapist write a letter saying I’m not insane. That should trump a birth certificate. That should be proof enough that this is real.