Dakis JoannouÔÇÖs Art Addiction

In the introduction to a new 856-page chronicle of his art-world life over the past 33 years, the Greek Cypriot collector Dakis Joannou writes that ÔÇ£when people ask how I define DESTEÔÇÖs programÔÇØ ÔÇö DESTE is the name of his art foundation ÔÇö ÔÇØI respond that I do whatever I want.ÔÇØ He also writes that ÔÇ£I am a prisoner of my own curiosity. An addict, perhaps.ÔÇØ

This combination of freedom (Joannou can afford it, since he owns a lot of real estate and a large construction company with projects across the Middle East) and compulsion (he has put a particular kind of investigatory patronage in the heart of his life) has made him at once influential and evasive. ThereÔÇÖs a reason why the collection and its associated activities go under the name of the foundation, and he often seems to operate at a kind of half-smile remove. The ever-more-bedazzling art world as a whole doesnÔÇÖt seem to concern him much, and he seems to look askance on many of the forces that drive it. But most basically, Joannou doesnÔÇÖt see himself as just another bigshot international art collector. And there are lots of those these days, after all.

I met up with him at his apartment high up in Trump Tower, where thereÔÇÖs serious-looking earbudded security in the lobby these days. JoannouÔÇÖs place is a kind of enchanted toy chest, full of the kind of amusingly haunting art heÔÇÖs often attracted to, starting with the seared, totemic stacked blobs of a Helmut Lang sculpture, arranged like a sinister shish kebab, that you meet when you walk in. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs his entire archive,ÔÇØ Joannou says, patting it affectionately, and when you look closer, you see on the skewer fabrics and papers and all kinds of things. Joannou tells me that he has owned the apartment since the building was new, in 1983, which is the same year that DESTE was founded, and two years before a young Citibank art-adviser executive named Jeffrey Deitch took him around the East Village. ThatÔÇÖs when he became transfixed by a work by a young artist named Jeff Koons, One Ball Total Equilibrium Tank, that he bought for $2,700 from the gallery International With Monument.

Back then, ÔÇ£You would come to New York, spend two days, and see much of what matters,ÔÇØ Joannou says. ÔÇ£Now, two days ÔÇö what am I going to see? Ten galleries? And so what?ÔÇØ he says. ÔÇ£The market grew out of my reach.ÔÇØ

His apartment now looks out on the flashy condo-campaniles of the global rich, a newly constructed set of mysterious skyscraping safe-deposit boxes. Similarly, what was in the 1970s a bohemian world apart, speaking with shabby defiance to itself ÔÇö Koons himself says in the book that before he met Joannou and his wife Lietta, he thought artists should stick with their own, and that he didnÔÇÖt ÔÇ£trust collectorsÔÇØ ÔÇö is now, for many, a fully financialized aesthetic-intellectual entertainment instrument. Or at least a lot more expensive.

But Joannou collects artists, not just art; as he sees it, itÔÇÖs about his relationships, these longstanding and evolving friendships. Almost from the beginning, his collection has been driven by ideas ÔÇö that this artwork is evidence towards recognizing advancing notions of who we are that he, personally, finds intriguing. A show he put up in 1996, named after a Jenny Holzer epigram, was called ÔÇ£Everything ThatÔÇÖs Interesting Is New,ÔÇØ and one of the artists in it, Martin Kippenberger, said, ÔÇ£I donÔÇÖt consider this kind of exhibition a ÔÇÿgroupÔÇÖ show. ItÔÇÖs more of a one-man show, of one person, a collector.ÔÇØ

Joannou helps these artists make what they want to make, publish what they want to publish. He doesnÔÇÖt hoard what he has (ÔÇØI never really had the urge to buy art to keep it for myself, to look at in private,ÔÇØ he writes in the book) but instead has always shown his collection, and has produced books to explain the ideas behind the work. ItÔÇÖs not that heÔÇÖs not a businessman ÔÇö he knows the value of these artworks and careers which he has encouraged and sponsored in various ways ÔÇö but for him, that is hardly the point.

And he does have great taste: Among the many artists he has had strong relationships with, besides Koons (he was even the best man at the artistÔÇÖs wedding to Ilona Staller, better known by her porn name, La Cicciolina) are Maurizio Cattelan and Urs Fischer. For many years, he worked with Deitch, who helped organize some of his more influential conceptual shows, perhaps most famously a 1990 one called Artificial Nature, which asserted that ÔÇ£Could it happen that the next generation will be our last generation of real humans?ÔÇØ (Please cross-check that idea with any nearby millennial.) HeÔÇÖs also had a longstanding curatorial alliance with the New MuseumÔÇÖs Massimiliano Gioni. But what the book mostly teaches is what interesting taste heÔÇÖs had in artists, many of whom, perhaps in part because of his interest in them, have turned out to be significant in various ways.

Part of the reason this book was made was to clear up what he saw as the misunderstandings around his involvement with a 2010 show at the New Museum, where he is a trustee. Called ÔÇ£Skin FruitÔÇØ and curated by Koons, it drew entirely from JoannouÔÇÖs own collection. Some observers saw it as essentially self-dealing among ÔÇ£art-world insidersÔÇØ; others, including New YorkÔÇÖs Jerry Saltz, defended it on the grounds that the art was interesting and, in any case, this is the way the real world works. ÔÇ£The end result of this is that I was put in with the other collectors,ÔÇØ Joannou tells me, seated at a table designed by Urs Fischer, one of the artists heÔÇÖs gotten to know and supported. With the book, ÔÇ£I want to record what we have done.ÔÇØ

DESTE is a foundation, but itÔÇÖs not a private museum, or an institute. The word means ÔÇ£look!ÔÇØ in Greek ÔÇö Joannou, from Cyprus, lives primarily in Athens ÔÇö and is also an acronym for ÔÇ£International Greek Contemporary Art.ÔÇØ Greece, especially in the 1980s, was an art-world backwater, and one of the effects of JoannouÔÇÖs activities is that the scene in Athens, especially, is now cross-pollinated better with the rest of the world.

Still, he notes, ÔÇ£Athens is a strange place because when you have a poetry reading, you can get a thousand people.ÔÇØ Art gets pushed down the food chain. ÔÇ£ItÔÇÖs the frame of mind. TheyÔÇÖre more about literature and poetry and music.ÔÇØ (He mentions that his son is an electronic-dance-music DJ.)

For eleven years, heÔÇÖs given out an annual DESTE Prize to a young Greek artist. A selection of artists, curators, patrons, critics, journalists, and other members of the itinerant global tastemaking class stop by the finalistÔÇÖs exhibition. The art-world types also come for the opening of a group show of under-33-year-old Greek and Cypriot artists called ÔÇ£The Equilibrists.ÔÇØ And dinner and dancing at his home.

And then some of them will be off to Hydra, a steep, dusty, impossibly picturesque nearby island known among Greeks as a formerly powerful trading center, and to the rest of us as the place Leonard Cohen moved in the 1960s. Joannou has a home there too, which he reaches by his yacht, Guilty, which was painted by Jeff Koons. (Previously, he owned a yacht named Protect Me From What I Want, after a Holzer phrase.) Since 2009, heÔÇÖs commissioned an artist every year to put on a show on Hydra in a former abbatoir overlooking the water. This year the slaughterhouse will be occupied by Roberto Cuoghi, who, Joannou expects, will do something ÔÇ£very strange.ÔÇØ

That happens this weekend. HeÔÇÖs looking forward to it.

This is a selection from his book of DESTEÔÇÖs doings for the past 33 years.

ÔÇ£A Guest + AHost = A GhostÔÇØ installation view (2009), with works by Urs Fischer.

Photo: Deste 33 Years

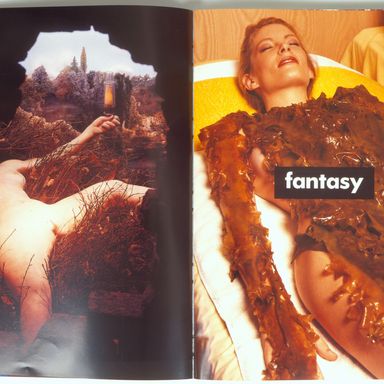

Spread from the Artificial Nature exhibition catalogue, designed by Dan Friedman.

Photo: Deste 33 Years

Kim Gordon installing Black Glitter Circle, 2008/2015.

Photo: Deste 33 Years

Maurizio Cattelan, WE, 2010. DESTE Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra.

Photo: Deste 33 Years

Jeffrey Deitch, Massimiliano Gioni, Dakis Joannou and Maurizio Cattelan during the preparation of ÔÇ£Monument to NowÔÇØ (2004).

Photo: Deste 33 Years

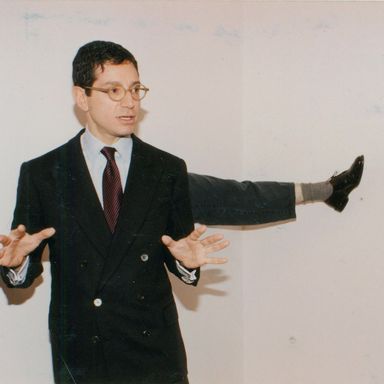

Jeffrey Deitch at the ÔÇ£Post HumanÔÇØ exhibition opening (1992), with Robert Gober, Two Spread Legs, 1991.

Photo: Deste 33 Years

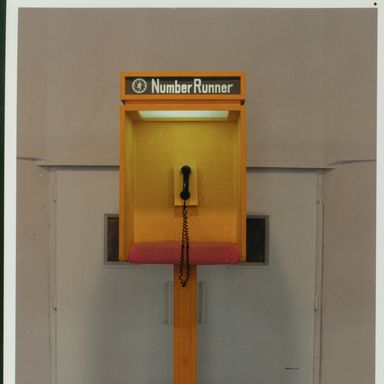

ÔÇ£Eliminating the AtlanticÔÇØ installation view (1990), with Laurie Anderson, Number Runners, 1979.

Photo: Deste 33 Years

Urs Fischer, YES (detail), 2013. DESTE Project Space, Slaughterhouse, Hydra.

Photo: Deste 33 YearsGuilty, 2008.

Photo: Deste 33 YearsJeff Koons, Dan Friedman, Jeffrey Deitch, and Dakis Joannou on vacation in Hydra, Greece (1987).

Photo: Deste 33 YearsJeff Koons at the ÔÇ£Spring Collection ÔÇÿ96ÔÇØ exhibition opening (1996), with Socratis Socratous, Gazon, 1991.

Photo: Deste 33 YearsLouis Durot, lÔÇÖEchauffeuse (1988), photograph by ToiletPaper for the project ÔÇ£1968: Italian Radical Design.ÔÇØ

Photo: Deste 33 YearsTim Noble & Sue Webster, Masters of the Universe, 2000.

Photo: Deste 33 YearsÔÇ£Post HumanÔÇØ installation view (1992), with Mike Kelley, Brown Star, 1991.

Photo: Deste 33 YearsÔÇ£PromenadesÔÇØ installation view (1985), with Mario Merz Il Numero Ingrassa (come) I Frutti dÔÇÖEstate e le Foglie Abbodanti 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34,...

ÔÇ£PromenadesÔÇØ installation view (1985), with Mario Merz Il Numero Ingrassa (come) I Frutti dÔÇÖEstate e le Foglie Abbodanti 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, 34, 55, 1974-85.

Photo: Deste 33 YearsÔÇ£Psychological AbstractionÔÇØ installation view (1989), with Robert Gober, Pitched Crib, 1987, and Günther Förg, Untitled, 1988.

Photo: Deste ...ÔÇ£Psychological AbstractionÔÇØ installation view (1989), with Robert Gober, Pitched Crib, 1987, and Günther Förg, Untitled, 1988.

Photo: Deste 33 YearsSkin Fruit installation view with Chris Ofili, RodinThe Thinker, 1997; Charles Ray, Aluminum Girl, 2003.

Photo: Deste 33 YearsIlona Staller and Jeff Koons at the ÔÇ£Artificial NatureÔÇØ exhibition opening (1990), with Jeff Koons, String of Puppies, 1988.

Photo: Deste 33 YearsMaurizio Cattelan and Dakis Joannou with Cini Boeri, Seprentone, 1971. Photograph by Pierpaolo Ferrari.

Photo: Pierpaolo Ferrari