Few directors in Hollywood history have a weirder filmography than Brian De Palma. He’s made some of the most successful movies of the last few decades — The Untouchables, Scarface, Mission: Impossible — but alongside them on his iMBD are such movies as Sisters, Obsession, and Body Double, films that are deliberately challenging and extreme, as well as art-house/mainstream crossover classics like Dressed to Kill and Blow Out, and major debacles like Bonfire of the Vanities.

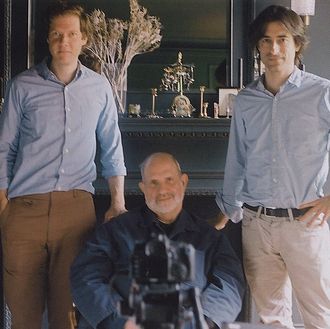

His experience has contained every version of a director’s career, and part of the wonder of Noah Baumach and Jake Paltrow’s new documentary, De Palma, is watching those alternative universes play out. For their documentary, which is being released by A24, Baumbach (The Squid and the Whale, Frances Ha, Mistress America) and Paltrow (The Young Ones) trained a camera on De Palma and talked to him for a week, cutting out their own voices. The result is one of the most clear-eyed and insightful documentaries about a director in recent memory. Vulture caught up with Baumbach and Paltrow to talk how they made the film, the changing landscape of Hollywood, and what makes De Palma unique.

There are a lot of directors who deserve this kind of treatment. Why did you decide to do this with De Palma?

Paltrow: It comes out of friendship — the whole impulse to make the movie is an extension of the time we got to spend with Brian talking about movies in general and, specifically, his movies. The way he’s sort of relaxed and open to talking about his experiences works because of that. It would be great to do it with other filmmakers, but we don’t necessarily know the ones well that we’d want to do it with.

Baumbach: The hidden narrative of this is our relationship with him. We took our voices out of the movie when we constructed it, but he was very much talking to us, and he has both the casualness and also a certain kind of preciseness coming from the fact that there was already a shorthand between us all.

Paltrow: He also knows what we’re trying to accomplish, that this is the unguarded version of this thing — and that if we got into territory that he wasn’t happy with, we weren’t going to use that bit. It’s not journalism.

How much tape of him talking do you have?

Baumbach: Like, 30 to 40 hours. It was about six years ago that we did the interview, and it took us about a year to edit it down.

You had him wear the same clothing throughout the interview.

Paltrow: Yeah, so that it wouldn’t be a distraction. You wouldn’t be jarred by: tan safari jacket, then blue safari jacket.

Baumbach: In a different kind of documentary, there’s the feeling of capturing the subject at different times, in different locations. But that wasn’t what this movie was. This was much more about keeping it singular, focused.

You take a movie-by-movie tour back through his filmography. Was that always the intention?

Paltrow: It’s a movie about a director by directors, so you’re getting into it through the films. That’s what we’re most interested in: talking about the movies and how he made them when he was young and what his process involves and how the landscape is shifting around him while that’s going on. There were a lot of stories that we already knew that we wanted to have him say again, but it’s a vast landscape to try to get through. The only method of doing it properly was to go chronologically, so at least you’re following the path.

Baumbach: We didn’t use notes or anything, either. We kept it conversational, which gave it a kind of built-in narrative — we always knew where we were going. That also gives the movie various narratives beyond Brian’s career: It’s a portrait of an artist and what it takes to have a long career, and specifically to have a long career in Hollywood from the late ’60s to now, which turns out to be a pretty interesting time and a time of great change.

What do you think Brian’s career has said about the way Hollywood has changed over that period?

Baumbach: The interesting thing about Brian’s career is that he really did keep figuring out ways to work within and outside the system. Even after Bonfire of the Vanities, he still had Mission: Impossible coming up, and even after Mission to Mars, you have Femme Fatale, an incredibly interesting movie, made in France, as a return to his subject matter of the late ’70s and early ’80s. He made movies that made a lot of people uncomfortable and pissed a lot of people off, and also movies that really pleased huge audiences. He’s somebody who really looks at himself as an outsider, too, which is an interesting characteristic for someone who very badly wanted to break into the system and work within the system when he started out.

Among the great American filmmakers from New Hollywood on, Brian seems to have been met with as much as resistance as any of his peers, except for maybe William Friedkin. What is it about Brian that makes critics and studios and audiences sometimes so uncomfortable with, and resistant to, his vision?

Paltrow: They’re singular works, and they’re extreme. I don’t think Brian ever made a non-R-rated movie [Laughs]. Even when he’s taking a job, as he would say, doing something that wasn’t generated by him, what he’s attracted to is extreme subject matter. That’s always something that makes people nervous.

Baumbach: And visually, he has such personality. He goes so big with the way he chooses to shoot things, with these long takes, swirling cameras. I remember watching Obsession in college. I’d seen it on TV a few years before with my father, and loved it, sort of unconditionally, but when I saw it in college, people were laughing in that way people laugh in college, to let you know they know the jokes but also when they get uncomfortable.

It wasn’t even a melodramatic scene — it was a scene with John Lithgow and Cliff Robertson sitting at a café in Venice, where, instead of cutting, the camera keeps rocking between them and shifting focus onto the background when it rocks. It’s peculiar, and it’s really interesting, but people didn’t know what to do with it. It’s that part of Brian as much as anything that makes him great and can also cause some kind of discomfort. It’s not familiar to people, and they don’t know what to do with it.

One of Brian’s comments in the movie that struck me was his remark about Hitchcock, about how Hitchcock’s technique of returning to and reusing visual tropes was sort of dying with him, and how Brian saw himself in that tradition. As good filmmakers in your own rights, what did you guys think about that statement?

Paltrow: That’s our big takeaway from the movie as well, and it’s something that I don’t think we discovered until the editing of the film was finished. Brian sees this visual language, this visual storytelling that starts with Hitchcock. Naysayers claim it’s appropriation, but it’s not. If you look at it like a language or a dialect, it becomes a really compelling way of looking at Brian’s movies, because he’s doing it consistently. People have made movies that we think of as Hitchcockian, which means you make one or two things in that vein, a Body Heat, or a … the one with Sharon Stone and Michael Douglas —

Baumbach: Basic Instinct.

Paltrow: — these movies that are overtly Hitchcockian, but then that person will go on and make something totally different and not necessarily visually driven. But Brian is working in this language that he’s talking about, and we both thought that was a very exciting thing. It’s a very bold observation to make about yourself, but it’s so true, and it changes the way you think of Brian. It’s the ultimate definition for me.

Baumbach: Right, and it’s also been leveled against him, especially throughout his early career, as a negative. But Brian has no trouble owning it.

Do you think that his focus on a visual language rather than plot or scale is one of the reasons why he might have less mainstream name-brand recognition than some of his contemporaries from the ’70s, like Steven Spielberg or George Lucas?

Paltrow: I think a lot of peoples’ experiences with Brian is, I didn’t realize he made this, or he made that. It’s a very strong flavor that’s out there that people know — they just have to be nudged a little bit. And obviously, the people who like Brian and his movies tend to do so fervently.