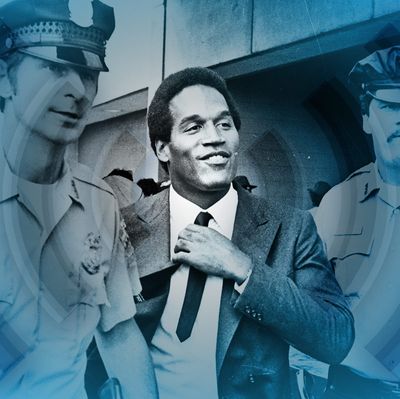

All this week, ESPN is airing O.J.: Made in America, the stunning five-part documentary series tracing the story of O.J. Simpson chronologically, from his beginnings as a college football star at USC all the way through the incident that landed him in prison, where he is today. But it’s also a story about race, fame, power, domestic abuse, and the LAPD’s history of brutality. In a wide-ranging conversation, Matt Zoller Seitz, Gazelle Emami, and Rembert Browne sat down with the documentary’s director, Ezra Edelman, for The Vulture TV Podcast to talk about what he left out, the disturbing charm of O.J. Simpson, and why he’s probably adapted well to prison. Listen to the conversation here, and read an edited transcript below:

Matt Zoller Seitz: At what point did you learn of the existence of FX’s The People v. O.J. Simpson, and what was your reaction?

Ezra Edelman: You hear that there’s a ten-hour dramatization happening, not that I am that familiar with Ryan Murphy’s work, but I was like, Okay, both, That is terrible from the standpoint of, we’re doing something this long, and someone at the same exact time is doing this? For a while I actually thought we were going to be done by October, so I operated under the illusion that we would be finished and the thing would be on television before that ever aired. [I had] a lot of the sort of feelings of, Oh, no one’s going to want to watch another ten hours of something, especially when it became clear that it was good, both critically and very popular — that was the fear. Here’s the thing: Regardless of my own paranoia about something that is both coincidental and maybe unfortunate, I certainly underestimated the culture’s fascination with the story, and there’s no doubt sitting here now that the existence of that show and its popularity has only helped drive interest in our doc. So I sit here now going, Okay, I’m glad there was an FX show.

Gazelle Emami: Did you expect to be telling such a relevant story when you started out?

EE: Certainly when I started out, I could not have known this spate of police violence that has been so public would take place. There are topics I knew were meaningful and that translate to today. The specifics of the things that have happened in the last two years, from when I began this, I couldn’t have known. Everything that happened in 1965, and seeing the evolution, even through O.J. as a media character and the superficial way he decided to go through the world, very much in contrast to the substantial times he came up in.

Rembert Browne: For me, one of the riskier things that got pulled off very well were these departures from ever mentioning or talking about O.J. I have to assume that while you’re building up the context, it makes great sense structurally in just telling the story. For me that was my favorite thing. I was like, Yeah, this movie is about O.J., but I just got a whole schooling on ’60s L.A. Were there moments where you were like, Maybe I’ve gone too far away from O.J., I need to pull it back?

EE: There was one question where there were a couple of people, who will remain nameless, who floated the question to others, but the reaction was sort of like Rembert. Like, No, that’s what I love about this. That we are engaged in this completely different plane for five to ten minutes at a time, and that you feel enlightened. Also, you’ve established a certain authority in the way you’re telling the story that people trust it’s there for a reason. I thought it was purposeful and necessary and right in how it was going to be structured. Once I got my head around the fact that tension was building in these two different places at the same time, and in some ways the violence is increasing in these two different places concurrently, that’s the way I thought about this. We’re getting closer and closer to aligning with these two stories in 1994, and that’s what kept me grounded in what I was doing.

RB: There aren’t really spoilers in terms of the chronological arc of what happens in the story, but part of the beauty of making this film is you get to decide what you tell, what you include, and also how to portray O.J. based off the questions you ask. I remember there was a point in the middle where I felt myself being very sympathetic to O.J. I was like, God, it’s just hard … being a black man in America. There were certain moments where I want to hate on him for some of the quotes he says, like the “I’m not black, I’m O.J.” It infuriates me, but there are points where I understand how hard it must have been. Were there points where you identified with him, and it just felt weird?

EE: I was reading a piece today about how he’s been erased from certain institutions; the USC Buffalo Bills don’t wanna include him in their very basic history. He’s still the best running back in franchise history, but it’s this very uncomfortable way of dealing with it, especially, because he’s not a convicted murderer, so you’re like, Are you allowed to do that? Drafting off of that sentiment is the idea of, there are going to be millions of people who don’t want to watch a story about him being a good guy. I’m just looking at the human being who was a lot more complicated and complex than what he’s been reduced to in the last 21 to 22 years. As far as the idea of his identity and the choices he made, yeah, I have empathy and sympathy. And then it goes away. […]

“I’m not black, I’m O.J.” is not defensible. But what’s less defensible is when it keeps going. When you get to the next part of, yeah, I’m at a wedding, and I overheard this white woman, and she says, “Oh, there’s O.J., sittin’ with all these niggers.” And then he’s, like, that’s great, cause you didn’t [include him in that]. Okay, you crossed the line, and I have a hard time getting into your headspace anymore. Then there is a schism that starts to happen that’s like, I don’t know what you’re all about.

GE: Going back to how he can come across as this charming, likable person at times in the documentary. I feel like those elements make it better, because it’s that much more chilling when you see what he’s capable of. You wouldn’t have as fully formed an idea of who this person is if you didn’t acknowledge all these other elements. And that really got to me in that Wendy Williams clip. You see her at the beginning, a little skittish around him, the normal reaction to having someone you believe is a murderer sitting next to you when you’re interviewing them. But by the end, she’s hugging him, she’s like, “I can’t help it, I like you, O.J., you’re damn likable.”

EE: Celia Farber, who’s a writer who wrote these two long pieces on O.J. around the same time, spoke very honestly about her own conflicted feelings of, you’re sitting next to a guy who committed murder, but you just don’t want it to be true because he is so charming and likable. She got OJ’d.

RB: I find that example being closer to an R. Kelly or Bill Cosby or people who we’ve time and time again forgiven because either we want to remember them before we knew all the bad stuff, or we’re just so captivated by their art or their sport or their charisma that it feels nice to turn off your brain for a bit. Watching this, I think the reason that it is almost like a Greek tragedy is because, especially for me, I just wasn’t aware of how incredible of a running back he was.

EE: The last thing I want to do is to get into any meaningful comparison between O.J. and Bill Cosby and R. Kelly, and degrees of badness, but there is something, especially in light of this Cosby situation. You believe O.J. is guilty of murder, right? But no one believes he’s a threat. That was such a specific, rageful, personal thing. And that probably has not shown up honestly outside of very specific environments — I don’t know if there have been that many people privy to the violence of him as a person. When you read the accounts by Cosby, just the deliberateness and the consistency of that deliberateness, it is … chilling. In a way that I’m more forgiving of Wendy Williams being charmed by O.J. than I might be at this point of someone being charmed by Bill Cosby.

MZS: I was intrigued by the structure of this thing, because you did not do what I think probably 95 out of 100 documentary series about this would have done, which was you didn’t start in the present and work your way back and alternate flashbacks throughout. We’re actually moving through his life chronologically, and it’s as if we’re reading a book.

EE: To experience the effect and the power of what this story is both in terms of who O.J. was as a man, and the concurrent history of that city leading up to a trial, I had a very clear desire to reframe how you would have absorbed the events of 1994 and ’95. The only way I feel you could have done that is to experience them in real time. In terms of who O.J. was as a man, his rise to celebrity, basically getting you in the mind-set of someone who lived through this history, so it is shocking and surprising that that guy is capable of these things. And then, on the other hand, that you can emotionally experience the violence meted out by the LAPD, understanding the long history and the consistency of these incidents.

By the time you get to the end of the story, you have seen a man in all his beauty and athletic glory in part one descend to this place in the course of one film. And you’re not jumping back and forth. You’re like, Oh, I was seduced by that guy, and I’m [repulsed] by that guy at the end.

GE: You have so much material. Were there any details where you were really like, Damn it, I don’t want to lose this one, but we just have so much other stuff we have to get in. We have to cut for time. We can’t make it any longer?

EE: I don’t know that I cut anything for time, but there are some things I would have liked to have explored that I couldn’t put in there based on what I had. The extent of O.J.’s cocaine use, for instance, which has been rumored going back to the ‘70s when he was in Buffalo. But to get real anecdotal evidence on the record about it combined with the actual purposefulness of it within the narrative, I didn’t have really either.

One thing I cut out, but it’s an interesting discussion, is the CTE issue. I had a whole scene about it in part five. Because, for me, if nothing else, narratively I would like to justify all the time I spent showing him play football in the first part of the film, beyond the need to just understand his greatness and his beauty and why people were seduced by him.

MZS: The CTE issue meaning the possibility that brain damage from football may have accounted for some of his behaviors?

EE: Yes. At first I talked to a guy who’s in the film who told me, “O.J. had a large head. In the ‘70s we used to have air padding in our helmets, and his head was so big he didn’t wear padding.” And you’re like, Okay. And he’s a running back, which, you know, they take a lot hits. He led the league in rushing twice. He led the nation in rushing twice at USC. He’s a guy who took a lot of punishment. Okay. Fine. And then I talked to Chris Nowinski, who was the expert at MIT who studies NFL player’s brains. He said, “Look, I would not be surprised if we were able to study O.J.’s brain after he passes away if he was found to have CTE.” Okay. Fine. Now, someone has to die before you examine their brain. That’s the only way to know if someone has CTE. That’s why it’s all speculative. Symptomatically, when this happens with people and how they act out, there tends to be a certain time frame, and it sets in five to ten years after they last played football. If you believe O.J. and the pattern of abuse went back as far as it did with Nicole to 1978, and potentially you’ve heard allegations with him and his first wife, and I’m like, No, I don’t think that’s explained by that. It’s something for us to discuss here, but I think in trying to offer an explanation for why O.J. had a history of violence, that’s a cop-out to me.

GE: You tried to get in touch with O.J. for this; you emailed him in jail. If you had gotten to talk to him, is there something you really wanted to ask him?

EE: I separate my desire to interview O.J. as a life experience and as someone who enjoys interviewing people from my desire to interview O.J. and put him in this film. I think that him in this film would not have made the film better. I don’t think he’s a reliable narrator. A lot of the things that this film was about is not stuff he’s ever particularly introspective and interested in talking about. He would have gummed up the works. I knew I was going to wait until I’d done a certain amount of work, if actually most of it, before I even reached out to him. And so I very much had the real thought that even if he had said yes, he might not appear until the last part of the film.

RB: I think one of the reasons so many of the people in the film have such incredible things to say is because he’s a mystery to everyone, and everyone has spent a decent chunk of their lives trying to make sense of it all. So by the time they’re asked questions about it, they’ve probably spent more time thinking about the inner workings of O.J. than O.J. has.

EE: I think that’s right. And also, unfortunately, as much as these people have been thinking about it, there haven’t been that many people who they’ve ended up being engaged with from a media standpoint that is overly thoughtful about it. They end up having to be on the other end of simple, crass, reductive questions that continue to have this story existing in the same place. As much as a lot of people did not want to participate, once they did it was like, Oh, I can unburden myself in a way that I haven’t felt comfortable before because I get that you’re not really coming here to figure out, is he guilty or innocent?

O.J. had a lot of friends. Now, I don’t know how O.J. thought of all these people in terms of how he classified people. But they all felt that they had this very clear personal bond. And that, again, speaks to the power of him. The only person that they could think of to compare him to was Bill Clinton, as far as the effect he has on you when he walks in the room and when you’re talking to him.

GE: Was anyone particularly difficult to interview in this process, in getting them to open up a bit?

E.E.: The hardest interviews to do for me were Mark Fuhrman … Barry Scheck was hard. Both of those were circumstances where you know they are not willing participants insofar as they have not talked about this for all this time in any meaningful way. And yet they’re public figures. If you’re talking to Fuhrman, when you’re sitting down with a guy like that, you’re like, Okay, but what’s my job? Is my job to sit across from him and determine if he’s a racist? How racist he is? I have to ask a question at some point just for my own journalistic integrity: “So you’re telling me that what I hear on those tapes is not reflective of your views and your experiences.” I at least know in an interview like that I have to be on the record saying it once if he’s not going to.

To get to Scheck, there’s a level switch. I already know he’s generally reticent to talk about this period. I can understand well enough what his reservations are. And so for me it’s just like, what’s the basic human way of asking the question that needs to be asked as a filmmaker even though I know he has an explanation as a criminal defense attorney?

GE: One thing I liked was how the documentary humanized the victims. Not just in taking a hard look at Nicole’s abuse, but, for example, in seeing A.C. Cowlings break down talking about her, you get a sense of what type of person she is. You also interview people like Fred Goldman and family members of Nicole. What was it like talking to people who have this completely different experience and who usually aren’t given a voice in this whole discussion?

EE: I’m glad, because I tried to do that as well. Fred Goldman was also [a hard one]. You realize you’re part of this machine that keeps churning, and it’s his son who was murdered. He’s torn by wanting continually to keep his son’s memory alive, which is very admirable, and also still driven by — I think hate is not a wrong word to use in terms of how he feels about O.J. He would be a lot more uncomfortable with having a nearly eight hour film about O.J. done if he weren’t a part of it. It’s hard. It’s just necessary. Because it’s the same reason why the crime-scene photos are in the film the way they are. You have to engage with the humanity of the victims themselves as well as the brutality of the crime. Or I will then have trafficked in the same exact thing that everyone has been trafficking in for the last 20 years.

GE: Fred Goldman particularly has been caricatured because of how much he spoke out about the trial.

EE: I don’t think that that guy deserves any scorn because of what he went through. Having said that, I understand why people have been critical of him. You can’t tell someone in that position to let something go. I don’t think anybody is appropriate in saying that. Yet there is the appearance of him being so aggressively public about going after O.J. in all these years, it’s hard not to feel uncomfortable with that. I talked to him a little bit about this. Is it a desire for money? Is it a desire for justice? I specifically asked about the accusations that they were just out for money when they published the book [If I Did It]. He was just like, “What am I gonna do?” There was a $33.5 million civil judgment against O.J. that was going to be divvied up between him, Ron’s mother, and the Brown family. Does it make him a bad person if he wants O.J. to pay when O.J.’s not paying? I don’t think so. So when you get to that point it’s like, I don’t know if it’s because he needs the money. But it’s like, to use his logic in his defense, a guy wrote a book that couldn’t be more offensive, tempting the public again saying, “If I did it.” I want to have nothing to do with it, I want to shut it down, and then I read it, and I’m like, This fuckin’ thing. It’s like he’s saying he did it. And so it’s like, And now we own it. Yeah, I’m gonna publish it. He’s never gonna say that. But he’s basically saying it. And so if we can publish it and have that out there for the world to see, and the by-product is we get paid for whoever actually buys the book …

GE: Was there anything that really surprised you, that you didn’t expect to find?

EE: When I saw the footage of O.J. inside his house the day of the verdict, I was like, “That’s pretty good.” That’s not something I’d seen before. The macro surprise versus the micro surprise was that everyone really went there in a lot of ways. Consistently, I would sit and have these conversations with people, and they were open and they were honest and they talked. That’s amazing. The humbling part of it is there’s so much that’s out of your hands.

MZS: There’s a sense in which this entire story, in addition to all the other things it is, it’s a story of a guy who’s trying to escape his own blackness.

EE: He’s a guy who’s trying to escape everything constantly. Blackness is just one of them. He was trying to escape poverty — even him marrying Marguerite, she’s the good girl from across town. That’s the first level that he advanced to, and then he gets to a college, and he’s around white people and rich white people, and then he advances to the next level. Then he moves to Bel Air. He’s constantly playing this game of climbing through American society and where he can shed the rung that’s below him. I have no sympathy for O.J. at the end, as some people have said. Some people watch this and really feel sympathetic toward him.

GE: Everything that you’re saying makes the end that much more bizarre. Just to see where he ends up. Even though you don’t feel sorry for him … it’s just unbelievable.

EE: Because of how fucked up the criminal-justice system is, there is this coda at the end where you can look at this and be like, Yeah, he shouldn’t have gone to jail for that long for that thing. That’s not right either. You have the most surreal farcical episodes in this robbery.

MZS: It’s some Elmore Leonard shit.

EE: It’s like some Elmore Leonard shit written by Hunter Thompson, and then you have the shlubbiness of the people with him, to the stupidity of the plan and what it was, to then being sentenced by a woman who ends up being a reality-TV judge. Sentencing him to 33 years for a crime that took four minutes and [he] didn’t do anything except go in and try and take back his own shit. You’re like, What are we talking about? And somehow it’s perfect for the end of this story, in a weird way.

I wonder what prison is like for him because I don’t know that it’s that bad. I don’t know anything about prison. I don’t ever want to go there. I just know that he’s not in a maximum-security prison; he has a lot of freedom walking around. I’m sure he has the respect of his fellow inmates. He’s adaptable. If nothing else, he’s adaptable.