Editor’s note: This story was originally published in 2016, shortly after the premiere of what was then the most recent TMNT movie, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Out of the Shadows. We are republishing it now that a new film about the Heroes in a Half Shell, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem, is in theaters.

The latest installment in the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles film franchise has arrived, and it’s been met with a resounding meh, earning much less in its opening weekend than its predecessor, and receiving critical jeers. That reception is a far cry from when the Turtles were first introduced to the world, back in 1984. Years before the cartoon, toy line, and movies turned them into a pop-culture phenomenon, the heroes in a half-shell debuted in an obscure, self-published black-and-white comic book that thrilled the comics market.

The success of their adventures in print sparked the establishment of a multitude of publishers looking to cash in on the TMNT craze with an array of bizarre imitators. Then, just as quickly as it began, the revolution went awry and a wide swath of the industry was eradicated almost overnight. The Turtles were inadvertently responsible for one of the most disastrous speculation bubbles in comics history: the so-called Black-and-White Boom and Bust of the mid-1980s.

It’s often forgotten that the Turtles were a comics property well before they became ubiquitous in other mediums (including, improbably, live musical performances). The characters were the brainchildren of two underemployed, New Hampshire–based art-school grads: Kevin Eastman and Peter Laird. During what Eastman would later call “late-night joking around,” he for no particular reason sketched out a turtle dressed up like a ninja. Laird countered with his own version. Then they co-drew a group shot featuring four such creatures. Icons were quietly born.

The two decided to take a leap of faith and do a full comic about these little doodle-dudes. It would be called Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, a title intended to parody comic-book trends of the day. “Teenage mutant” was a riff on the X-Men franchise (which starred teenaged mutants), “ninja” to poke fun at the martial-arts-filled work of writer Frank Miller on Daredevil and Ronin, and “turtles” to reference indie-comics darling Cerebus (which starred a talking aardvark).

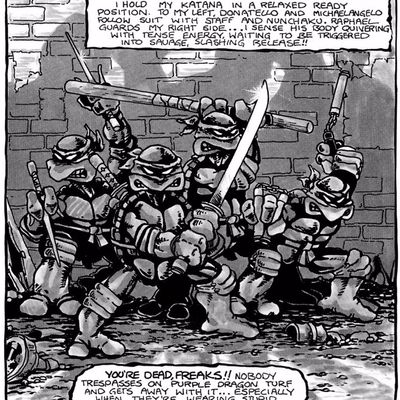

But what made the book interesting — and its eventual appeal universal — was the fact that it wasn’t just parody. Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles was also an action-packed, violent, and dark story, far removed from the Day-Glo silliness of later Turtles incarnations. Eastman and Laird couldn’t afford to release the comic in color, so they’d followed the lead of those other acclaimed indie comics by printing in black and white, which made it look more mature next to the childishly colorful titles from Marvel and DC Comics.

The creators pooled their cash and borrowed $1,300 from Eastman’s uncle to pay for a print run of 3,000 copies, then set up a deal with a distributor to ship them to comics shops. They also sent out about 180 press releases to niche and mainstream news outlets. There was something about the comic — perhaps its tapping of the Zeitgeist, perhaps its acrobatic action, perhaps its humor, most likely all three — that resonated with readers. Buyers scooped up the copies Eastman and Laird put out through comics shops and in individual sales at conventions. In three weeks, they were sold out. Word of mouth grew, and so did print runs and sales for subsequent issues. In that crazy whirlwind of enthusiasm for this newly arrived hit, the bubble began to form.

First came the consumers. The scarcity of that initial print run meant buyers lucky enough to have copies could sell them to collectors for as much as $100 in 1985 — a markup of more than 6,600 percent. Comics speculators seeking similar ground-floor investments started snapping up other comics that could appreciate in value, and even non-speculators became interested in reading more stuff like the adventures in TMNT. Thus, the demand for black-and-white, action-packed, somewhat-parodic series spiked.

It was a perfect recipe for quick wealth. Making something in black and white on flimsy paper was a cheap endeavor, so the potential profit margins were incredible. Publishers proliferated at a rate no one had seen in decades. According to industry trade Comic Buyer’s Guide, there were ten independent publishers in early 1984 and 170 by the end of 1987. Silverwolf Comics, Adventure Publications, Crystal Publications, ACE Comics, Solson Publications, Lodestone Comics, New Sirius Productions, the ironically titled Pied Piper Comics — the list went on and on. Naturally, retailers were happy to act as middlemen, buying up the new products from fly-by-night publishers and serving it up to the consumers who craved it.

Since TMNT had been a parody of popular comics that, itself, became popular, the new publishers often decided to make their own parodies of the Turtles. Just a few of the improbable rip-offs: Adult Thermonuclear Samurai Elephants, Mildy Microwaved Pre-Pubescent Kung Fu Gophers, Geriatric Gangrene Jujitsu Gerbils, Adolescent Radioactive Black Belt Hamsters, and my personal favorite, Pre-Teen Dirty-Gene Kung-Fu Kangaroos. There were more run-of-the-mill superhero and fantasy comics, too, most of them crudely drawn and poorly plotted. That low quality was to be expected, as some publishers were debuting as many as 19 titles at a time — an insane burden for a publisher with no capital to hire top talent.

“Any potential profiteer who smelled a buck in comics crawled out from under the muck and started publishing like mad,” wrote the esteemed comics columnist Gary Groth in a 1987 post-mortem about the bubble. In his estimation, these thrown-together publishers greeted the market “with all the enthusiasm and integrity of purpose as a brothel greeting the debarkation of the 5th fleet.”

Although some shops were well-intentioned in their attempts to show off work from independent writers and artists, there were plenty of bad apples. In 1986, at the height of the craze, one businessman secretly financed four competing publishers. Sales numbers from that era are hard to find, but a commonly cited statistic says a typical indie publisher before the boom would print only about 10,000 copies of a comic. During the boom, the indie market was lucrative enough that a publisher could print up 100,000 to 200,000 copies of a given issue.

Those huge print runs, of course, should have been a red flag for anyone watching the industry. After all, what made TMNT successful was its uniqueness: artistically, it stood out because there was nothing else like it in the market, and the value of issues resulted from those tiny print runs. Once consumers were faced with hundreds of titles, each of them available in abundance, the idiosyncrasy and scarcity disappeared. “Americans are nothing if not bored easily,” Groth wrote. “At some point — my guess is around September or October of ‘86 — they got bored.”

In late 1986 and 1987, the bottom fell out. Hard. Collectors stopped paying top dollar for new number-one issues. Dissatisfied readers stopped buying the new wave of black-and-white comics. Retailers, who’d over-ordered copies of the stuff, felt the financial burden of a glut of unsold comics they couldn’t return. Publishers couldn’t convince retailers to get back onboard and they started going under. The shock to the market even hit the distributors who’d been handling all this new product for the past year or so, and one — Glenwood — went out of business. According to industry analyst John Jackson Miller, sales of books from the black-and-white publishing start-ups fell by half in 1988. The era of black-and-white excitement was over.

By that point, TMNT had started printing in color, and Eastman and Laird kept interest in their comic uniquely high because they’d snagged lucrative deals to adapt the characters into toys and animation. Marvel and DC had never really invested in the Black and White Boom, so their sales remained steady. But the crash reverberated in comics shops and reader conversations. Retailers, collectors, and publishers should have learned an important lesson about frenzied comics fads.

Unfortunately for the industry, they didn’t. Though the black-and-white sector of the industry never became a phenomenon again, the world of color soon saw its own catastrophe, one of much more epic proportions. In the early 1990s, comics from big superhero publishers like Marvel, DC, Image, and Valiant went through a similar collective insanity: massive print runs for purportedly “collectible” issues followed by a mid-decade crash that bankrupted Marvel and made the superhero an endangered species.

What salvaged the comics industry after that second boom-and-bust cycle? In many ways, it was the game-changing success of superhero movies like X-Men, Spider-Man, and Batman Begins. The box-office receipts they raked in underwrote Marvel and DC’s publishing efforts and led to the former being snatched up into the protective arms of Disney.

Movies adapted from comics have since become the financial pillars of not just comics publishing, but modern filmmaking. There are seven superhero movies out this year and at least seven superhero TV shows, all of them trying to ride the seemingly endless spandex wave. But the laws of gravity apply today as much as they did during the Black and White Boom. That market calamity is a reminder that even the best, most lucrative entertainment ideas can get diluted and bastardized to the point of irrelevance and financial disaster. Perhaps that’s something Paramount should keep in mind as it mulls the future of the Turtles franchise.